Themes > Features

10.03.2010

FDI and the Balance of Payments in the 2000s

A major component of the economic reform initiated in the 1990s was, and remains, the liberalisation of regulations relating to the inflow and terms of operation of foreign direct investment (FDI). An important reason for seeking to attract such capital is the belief that such inflows, besides enhancing the level of foreign exchange reserves in the short run, would use India as a base for world market production, improve the competitiveness of Indian industry, increase exports and render the balance of payments sustainable in the medium and long term. As a result, successive governments have sought to better past records in terms of the annual inflow of such investments.

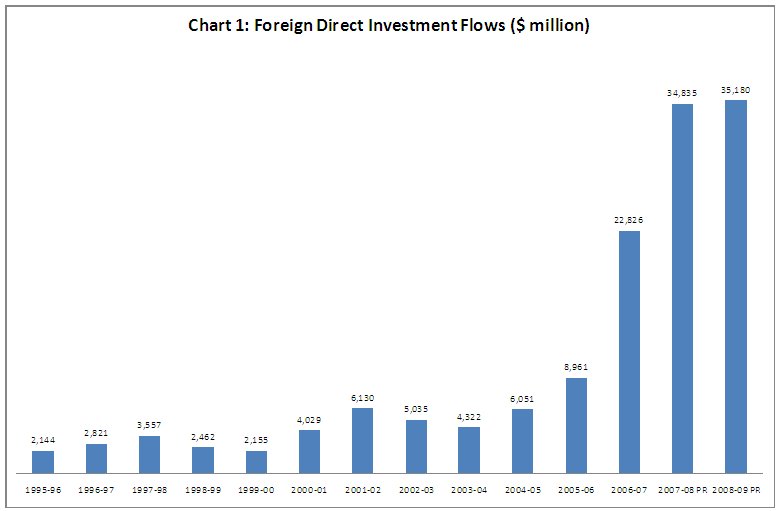

It cannot be denied that these efforts at attracting inflows have been

successful. While there is reason to be wary about treating all recorded

FDI as consisting of capital entering the country with a long-term,

productive interest, especially since it requires just 10 per cent equity

by a single foreign investor for a firm to be treated as a foreign direct

investment company (FDIC), a substantial inflow of capital under this

head cannot be denied. FDI inflows which stood at about $2 billion in

the middle of the 1990s and touched $4 billion in 2000-01 rose sharply

to $6 billion in 2004-05, and then registered a sharp spike to touch

$22.8 billion in 2006-07, $34.8 billion in 2007-08, and $35.3 billion

in 2008-09 (Chart 1).

Not

all of this, it must be noted, is investment in greenfield projects.

In the wake of liberalisation of ceilings on foreign shareholding, from

the 40 per cent level required for national treatment under FERA, a

number of companies already in operation in the country raised the foreign

stake in their paid-up capital through issue of new shares to the foreign

investor.

Further, there have been a large number of cases of foreign firms acquiring

wholly Indian ones. Data relating to inflows on account of acquisition

of shares of Indian companies by non-residents under section 29 of FERA

and Section 6 of FEMA is available from January 1996. While the share

of FDI inflows on this account has been substantial in some years, accounting

for 23 per cent of the total in 2006-07 for example, the figure has

generally been around 15 per cent of the total.

Table

1: Export Intensity of Sales of Selected FDICs |

||||||

No

of firms |

E/S

(%) |

|||||

| 2001-02

|

490 |

14.1

|

||||

| 2002-03

|

490 |

14.8

|

||||

| 2002-03

|

508 |

14.7

|

||||

| 2003-04

|

508 |

15

|

||||

| 2004-05

|

518 |

12.6

|

||||

| 2004-05

|

518 |

12.2

|

||||

| 2004-05

|

501 |

11.1

|

||||

| 2005-06

|

501 |

11.9

|

||||

| 2005-06

|

524 |

15.5

|

||||

| 2006-07

|

524 |

16.4

|

||||

| 2006-07

|

502 |

13.8

|

||||

| 2007-08

|

502 |

15.4

|

||||

The fact that FDI inflows do not always reflect investments in greenfield projects is not without significance. Both foreign firms set up during the years when FERA limited foreign shareholding to 40 per cent and Indian companies established during the import substitution phase of Indian industrialisation were created with the domestic market as their primary targets. In the case of foreign firms, quantitative restrictions and high tariffs forced those that could earlier service the Indian market with exports from the parent or third-country subsidiaries to jump tariff barriers and set up capacity within the domestic tariff area in defence of existing markets. On the other hand, the large market ‘opened up’ to domestic entrepreneurs by protection, which was expanding as a result of state investment and expenditure, provided a major stimulus for the creation of new indigenous firms by Indian industrialists to cater to the local market. The net result was that even when the world market for manufactures was expanding quite rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s, both foreign-owned and domestic firms from India were conspicuous by their absence in international markets.

Table

2: Ratio of Imports to Exports |

||||||

No

of firms |

M/X

(%) |

|||||

| 2001-02

|

490 |

79.9

|

||||

| 2002-03

|

490 |

77.7

|

||||

| 2002-03

|

508 |

92.1

|

||||

| 2003-04

|

508 |

97.2

|

||||

| 2004-05

|

518 |

123.2

|

||||

| 2004-05

|

518 |

141.7

|

||||

| 2004-05

|

501 |

145.7

|

||||

| 2005-06

|

501 |

150.5

|

||||

| 2005-06

|

524 |

129

|

||||

| 2006-07

|

524 |

154.8

|

||||

| 2006-07

|

502 |

144.1

|

||||

| 2007-08

|

502 |

158.5

|

||||

Given

the evolution of these firms, it should be expected that any increase

in the equity stake of the foreign investors in existing joint ventures

or purchase of a share of equity by them in domestic firms does not

automatically change the orientation of the firm. As a result, in such

cases FDI inflows need not be accompanied by any substantial increase

in exports, whether such investment leads to the modernisation of domestic

capacity or not. Moreover, if the domestic market is attractive for

these firms, there is no reason to believe that when the market is expanding

and diversifying rapidly, foreign investors in greenfield projects too

(such as in automobiles or telecommunications) would not target the

domestic market.

The available evidence suggests that this is precisely what is occurring

in India. The Reserve Bank of India has periodically been publishing

figures on the finances of Foreign Direct Investment Companies (FDICs),

or companies in which a single non-resident investor has 10 per cent

or more shares, for different sets of years since the 1990s. These firms

are those, with the requisite foreign equity holding, included in the

RBI’s studies of the finances of a larger sample of public and private

limited companies. It must be mentioned that neither do these data sets

amount to a comprehensive census of FDICs nor are they a consistent

sample in the sense that the firms covered remain the same in all years.

The number of firms covered in each year’s selective survey, which provides

data for two or three consecutive years for a common set of firms, varies

over time. So the series is not strictly comparable over a long period.

However, the numbers are indicative.

Table 1 provides details on movements in the exports sales ratio for

these sets of firms for the period 2001-02 to 2007-08. What the numbers

indicate is that in the period when FDI inflows into India have been

rising rapidly, the export intensity of FDICs has been more or less

stable. This fact counters the presumption of many who argue that, in

the context of globalisation, FDI flows reflect the need of large international

firms to seek out the best locations for world market production, resulting

in a virtuous nexus between FDI and exports.

But this is not all. Since the relaxation of controls on FDI inflows

under reform is accompanied by the liberalisation of the rules governing

the operation of foreign firms and is accompanied by substantial trade

liberalisation, we can expect two tendencies. First, there could be

greater expenditure of foreign exchange by these firms on imported inputs.

Second, there could be greater expenditure of foreign exchange because

of the larger payments on account of royalties and technical fees and

larger repatriation of profits as dividends encouraged by the more liberalised

environment.

The

first of these is most likely. To start with, foreign firms would seek

to use trade liberalisation and the liberalisation of regulations with

regard to use of international brand names, to cash in on the pent-up

demand among the more well-to-do for a range of product innovations

available in the international market place, access to which was restricted

in the protectionist phase. Even if the market for this range of ‘new’

products is small, they can be ‘manufactured’ and sold in the domestic

market with relatively small investments at the penultimate stages of

production, based on imported intermediates and components. Not surprisingly,

therefore, as Table 2 indicates, the ratio of imports to exports from

FDICs has been rising rapidly. This trend could also reflect the possibility

that reduced restrictions on imports are intensifying the practice of

‘transfer pricing’ or imports from the parent or a third-country subsidiary

located in a tax haven at inflated prices, so that profits are ‘transferred’

to firms in low tax locations. This obviously implies that the foreign

exchange cost of domestic production is inflated further.

These

factors operate together with the tendency to extract larger payments

in the form of more ‘open’ transfers such as royalties and technical

fees. For all these reasons, the operations of foreign firms can result

in a significant drain of foreign exchange. To the extent that these

tendencies are associated with investments focused on exploiting the

domestic market, there would be little by way of enhanced foreign exchange

earnings to neutralise their adverse balance of payments consequences.

In the event, the net balance of payments impact of FDI inflows can

be negative.

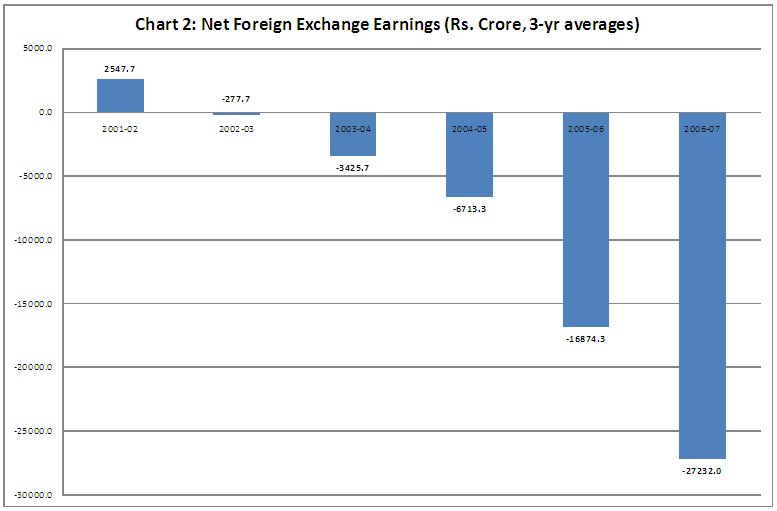

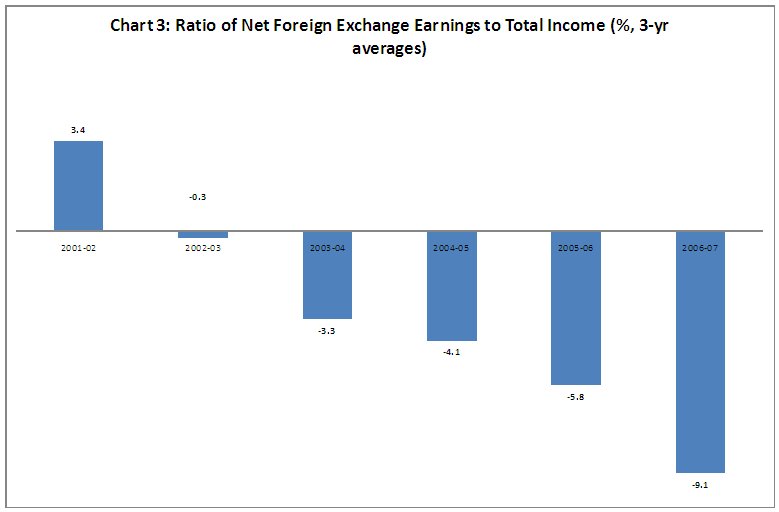

As

is clear from Chart 2, which provides three year average figures for

a common set of firms, there has been a sharp increase in the net outflow

of foreign exchange (or a negative value for total foreign exchange

earnings minus foreign exchange expenditures) on account of the operation

of FDICs in the country between 2002-03 and 2006-07. This holds true

even if we normalise these figures with the total income earned by these

firms, with net earnings moving from a positive 3.4 per cent in 2001-02

to a negative 9.1 per cent in 2006-07, where the figures again are three-year

averages (Chart 3).

It could, of course, be argued that the drain of foreign exchange on

account of the operations of these firms is more than matched by the

additional inflow in the form of equity capital. This argument, however,

confuses the immediate inflow on account of foreign investment and the

long-term impact of the operation of an FDIC. It is well known that

foreign capital inflows into joint ventures in developing countries

are in the nature of large one-time flows for establishing or substantially

expanding an enterprise accompanied by smaller ‘in effect’ inflows on

account of retention of part of the profits due to the foreign partner,

which are not paid out as dividends.

Once established, much of the expansion of the firm occurs on the basis

of borrowing from the domestic market. Such expansion results in an

increase in the fixed assets, sales and profits of the company concerned,

which in turn increases outflows on account of imports and non-import

foreign exchange expenditures like royalties that are tied to sales

volumes.

Thus, unless export revenues increase significantly and bring in additional

foreign exchange revenues, net inflows that are positive at the time

when equity is flowing in soon turn negative, and within a short period

cumulative inflows are negative. It is for this reason that the cumulative

foreign exchange impact of foreign investments targeted at domestic

markets inevitably tends to be negative. There is no reason to believe

that the story is different with respect to FDI flows into India after

liberalisation.

©

MACROSCAN 2010