Themes > Features

09.03.2012

The Age of "High" Oil *

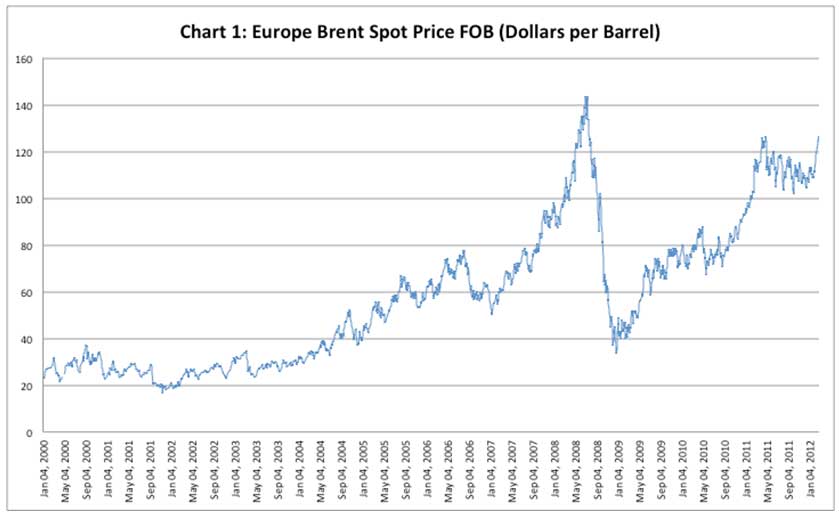

The predicament in Europe has thus far diverted attention from another crisis that has been brewing for some time now: a spike in global oil prices. The price of oil has risen by close to 20 per cent since the beginning of this year, raising the prospect of it touching the peak levels it had reached in July 2008. Brent Crude was selling at $128 a barrel at the beginning of March, as compared with its less-than-$110-a-barrel price at the end of December (Chart 1). This spike occurred on top of the continuous increase in prices recorded since December 2008, when oil prices touched a low influenced by the global crisis. Prior to that the free-on-board (FOB) price of Brent crude had collapsed from more than $140 per barrel in July 2008 to less than $35 a barrel by the end of that year. But though the recession has persisted even after that, the price trend has reversed itself to reach its current high levels even by historical standards. In fact, if Europe was not experiencing the stagnation it is struggling to address, oil prices could possibly have been at another record high.

From a purely demand-supply point of view, the rise is indeed surprising.

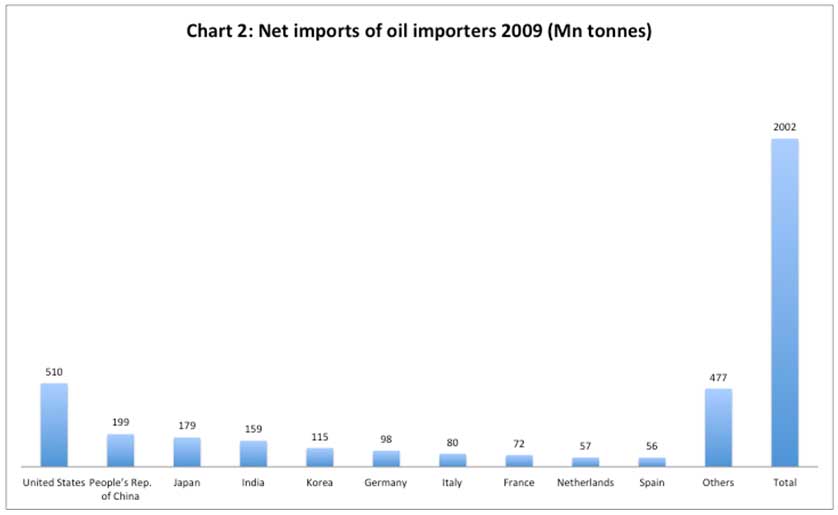

The US, the world's largest importer (Chart 2), has seen its import

levels drop significantly. One reason is that the combination of a recession

and higher oil prices has restrained oil demand. According to official

sources, the demand for oil in the US was down by 2 per cent last year.

In addition domestic supply has improved, partly because of increased

domestic production and partly because of the availability of alternative

fuels such as ethanol. As a result the share of imports in US oil consumption

was down to 45 per cent from 60 per cent in 2005. Aggregate US imports

of crude oil are placed at 8.91 million barrels a day in 2011, which

was the lowest it has reached after 1999. All this should have worked

to moderate international oil prices.

It could be argued that the fallout of these trends in the US has been

partially countered by the increase in Asian demand. China and India

are the second and fourth largest net importers of oil. But in their

case too growth, though higher than in Europe, the US and Japan, has

slowed after the crisis. So demand from those sources too would have

been lower than would have otherwise been the case.

If prices have risen sharply despite these trends, it is principally

because of the uncertainty resulting from political developments in

the region. Ever since the outbreak of diverse oppositional movements

in West Asia and North Africa, uncertainty with regard to supplies has

been on the rise. The political disruption in Libya in particular was

seen as having had an adverse effect on supplies. But the factor that

seems to have provided a fillip to the price rise was the standoff between

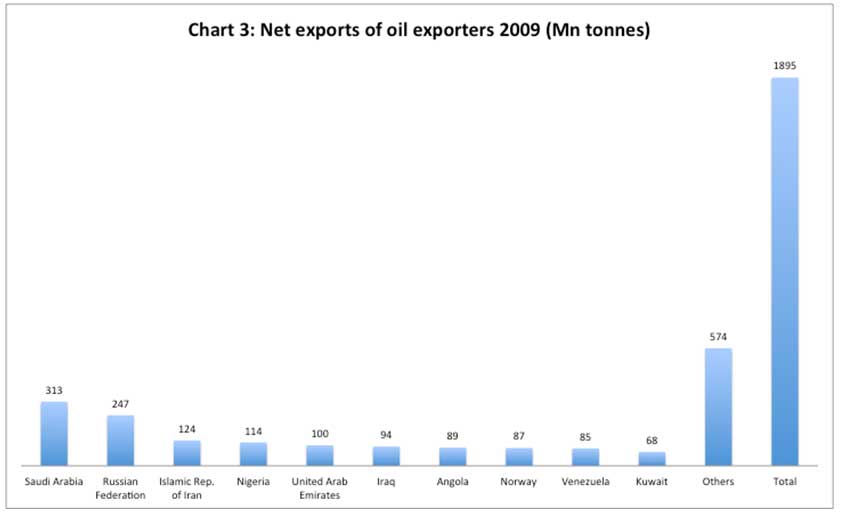

Iran and the West, ostensibly over the former's nuclear programme. Iran,

which is third largest net exporter of oil (Chart 3), is already subject

to US sanctions that are targeted at limiting its oil exports. In fact,

in recent times, the US has intensified its efforts to discourage global

consumption of Iranian oil. To add, Europe announced that it would also

impose an embargo on oil imports from Iran starting from July this year,

and Iran responded by threatening to immediately cut supplies to six

European countries.

The price spike, however, was not because of any immediate shift in

the supply-demand balance and shortfall in oil availability resulting

from these factors. To start with, the announced European embargo and

Iran's response to it have yet to be implemented. Secondly, the US has

not been able to persuade all countries to stop oil imports from Iran,

which would have effectively cut off its supplies to world markets.

A typical case here is India. India imports around 300,000 barrels of

oil a day from Iran, which amounts to a significant share of its oil

consumption. Yet India seemed to be succumbing to pressure from the

US, first with respect to a transnational pipeline project involving

Iran and subsequently with regard to foreign currency payments arrangements

for Iranian oil. But finally, India has worked out a rupee payment deal,

which secures its supplies from Iran as well as opens up opportunities

for trade reminiscent of India's relationship with the erstwhile Soviet

Union. Besides India's action, Iran's supplies to the world market are

likely to remain untouched because of the importance of Asia in its

total exports. China, India, Japan and South Korea account for more

than 60 per cent of world imports of Iranian oil. So long as these countries

protect their own energy security by not cutting off their relationship

with Iran, a chunk of supplies involved in the global trade in oil would

not get cutoff.

Finally, as in the past Saudi Arabia has helped cool oil markets with

its spare capacity and its willingness to ramp up production to cover

any unmet demand. Saudi Arabia had made an important contribution to

reining in oil prices during the Venezuelan oil strike in 2003, the

invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the Libyan crisis last year, and promises

to continue to do so.

If despite all these factors that keep the supply-demand balance in

control, prices have risen, it is because of the speculation engaged

in by global finance by exploiting the prevailing political uncertainty.

It is known that energy markets have attracted substantial financial

investor interest since 2004, especially after the decline in stock

markets and in the value of the dollar. Investors in search of new investment

targets have moved into speculative investments in commodities in general

and oil in particular. Hedge funds and other investors have been buying

into the commodity, fuelling the price increase even further.

The problem is that this consequence of speculation is not just a short-term

price spike. If speculation feeds on political uncertainty, then we

could be looking at a long-term problem in oil markets. As noted earlier

(Chart 1), looking back it emerges that nominal oil prices were rising

gradually from 2003 till the middle of 2006 and sharply from early 2007

till the middle of 2008, after which we have witnessed the dip and revival

since 2008. That is, the last decade, when political turmoil intensified

in the West Asian region, has been a period of an almost continuous

increase in oil prices, irrespective of the state of global demand.

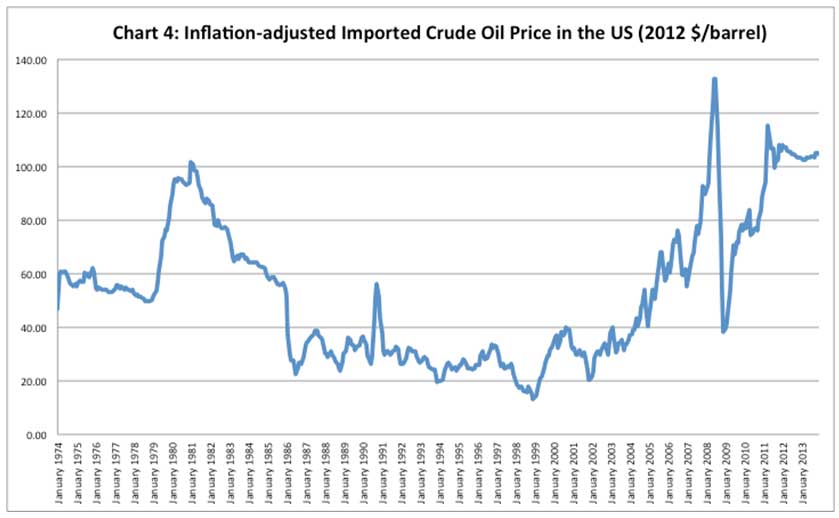

This is by no means a normal inflationary trend, since even the real,

consumer price inflation-adjusted price of oil has been at high levels

in recent years. Consider, for example, the price of oil imported into

the US, measured in inflation-adjusted terms or in ''2012 dollars''

(Chart 4). The chart shows that the real price of oil has been on the

rise since 1999 and especially since September 2001, when the US responded

aggressively to the twin towers attack. What is more, the peak 2008

price in 2012 dollars was above the high prices recorded in the 1970s,

which was when the world experienced the effects of the formation of

OPEC, the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq war. In sum, ever since

''9/11'', oil prices have not just been on the rise but seem to have

found a higher average level when compared with trends since the formation

of the OPEC cartel.

It has been known for sometime that this long-term trend was not really

the result of fundamental demand-supply imbalances but driven by financial

speculators exploiting political uncertainty. In April 29, 2006 the

New York Times had reported that: ''In the latest round of furious buying,

hedge funds and other investors have helped propel crude oil prices

from around $50 a barrel at the end of 2005 to a record of $75.17 on

the New York Mercantile Exchange.'' According to that report, oil contracts

held mostly by hedge funds had risen to twice the amount held five years

ago. To this had to be added trades outside official exchanges, such

as over-the-counter trades conducted by oil companies, commercial oil

brokers or funds held by investment banks. And price increases had also

attracted new investors such as pension funds and mutual funds seeking

to diversify their holdings. In fact, in November 2007, when Royal Dutch

Shell, Europe's biggest oil company, presented its third quarter results,

Chief Financial Officer Peter Voser argued that: "The price (of

oil) seems to be driven by some speculation and also has a political

premium in it rather than actually some of the fundamental drivers."

These trends have only intensified since.

Not surprisingly, in 2008 the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting

Countries (OPEC), which is normally held responsible for all oil price

increases had asserted that oil has crossed the $100-a-barrel mark,

not because of a shortage of supply but because of financial speculation.

OPEC's contribution was indirect and unintended if at all. As A.F. Alhajji,

Energy Economist and Associate Professor at Ohio Northern University

had argued in the Financial Times, even when some OPEC countries are

to blame it is because: ''As oil prices have increased, so have their

(OPEC countries') revenues. Some of these revenues found their way into

funds that speculate in oil futures.'' In his view, it was in this way,

ironically, that ''petrodollars'' have helped drive oil prices to record

levels.

In sum, a combination of political uncertainty, partly generated and

sustained by US and European foreign policy, and the operations of global

finance, has taken the world into a higher oil price regime. Such uncertainty

and the accompanying speculation hold out the threat of an age of ''high

oil''. We seem to have forgotten that. But recent developments are once

again bringing that truth to the forefront.

*This

article was originally published in the Business Line on 5 March 2012.

©

MACROSCAN 2012