Themes > Features

06.05.2004

Managing the Capital Flow Bonanza

C.P.

Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

On

April 23, India's foreign exchange reserves stood close to $118 billion.

This implies that during the first three weeks or so of financial year

2004-05, reserves had risen by around $5 billion. This reflects the

continuation of a trend that has been operative for quite sometime now.

The foreign exchange assets of the central bank rose sharply, from $42.3

billion at the end of March 2001 to 54.1 billion at the end of March

2002, $75.4 billion at the end of March 2003 and $113 billion at the

end of March 2004. This implies that even after discounting for the

increase in reserves resulting from the appreciation of the dollar value

of the RBI's Sterling, Yen and Euro reserves, the foreign exchange assets

of the central bank were rising by around $980 million a month in 2001-02,

$1.4 billion a month in 2002-03 and $2.5 billion a month during 2003-04.

The process of reserve accumulation is the result of the pressure on

the central bank to purchase foreign currency in order to shore up demand

and dampen the effects on the rupee of excess supplies of foreign currency.

In India's liberalized foreign exchange markets, excess supply leads

to an appreciation of the rupee, which in turn undermines the competitiveness

of India's exports. Since improved export competitiveness and an increase

in exports is a leading objective of economic liberalization, the persistence

of a tendency towards rupee appreciation would imply that the reform

process is internally contradictory. Not surprisingly the RBI and the

government have been keen to dampen, if not stall, appreciation.

The Indian rupee's appreciation vis-à-vis the dollar began in

June 2002, when it had touched a low of more than Rs. 49 to the dollar.

More recently, the rupee has been rising vis-à-vis the Euro as

well over the last four months. During these periods of ascent, it has

appreciated by close to 12 per cent vis-à-vis the dollar in 22

months and by a significant 9 per cent vis-à-vis the Euro in

a short period of 4 months. Not surprisingly, exporters have begun to

get restive; since a loss of 10 per cent in the rupee price of their

exports can shave off margins on past fixed-price dollar/euro contracts

and make it difficult to win new orders.

The rise of the rupee is partly attributable to the depreciation of

the other currencies, especially the dollar against those of its competitors.

That this was true for some time is reflected in the fact that while

the rupee was appreciating against the dollar for close to two years,

it was depreciating vis-à-vis the euro for much of this period.

This is, however, only small cause for comfort, since most export contracts

are denominated in dollar terms. Moreover, in recent months, as noted

above, the rupee has been appreciating against the euro as well.

Since these were periods when the RBI was purchasing foreign currencies

and fattening its reserves, it should be clear that exchange rate management

through currency market intervention had been crucial in dampening the

rupee's appreciation vis-à-vis the dollar and relative stability

vis-à-vis the Euro. Unfortunately, the RBI's ability to persist

with this policy without eroding its ability to control domestic money

supply is increasingly under threat.

The task of managing the rupee is daunting because, when the central

bank increases its foreign currency assets to hold down the value of

the local currency, there would be a corresponding matching increase

in the liabilities of the central bank, amounting to the rupee resources

it releases within the domestic economy to acquire the foreign exchange

assets. If forced to continuously acquire such assets, the resulting

release of rupee resources would lead to a sharp increase in money supply,

undermining the monetary policy objectives of the central bank. Since

financial liberalization implies abjuring direct measures of intervention

to curb credit and money supply increases, the central bank has sought

to neutralize the effects of reserve accumulation on its asset position

by divesting itself of domestic securities through sale of government

securities it holds.

This process of ''sterilizing'' the effects of foreign capital inflows

through sale of government securities has, however, proceeded too far.

The volume of rupee securities (including treasury bills) held by the

RBI has fallen from Rs. 150,000 crore at the end of March 2001 to Rs.140,000

crore at the end of March 2002 and Rs. 115,000 crore at the end of March

2003, before collapsing to less than Rs.30,000 crore by the end of March

2004. The possibility of using its stock of government securities to

sterilize the effects of capital flows on money supply has almost been

exhausted.

It was possibly this factor which accounted for the reticence of the

central bank to hold back on currency purchases in recent weeks, resulting

in a faster appreciation of the rupee. Fortunately for the RBI, it was

helped on this front by the uncertainty created by the results of the

exit polls conducted midway through the Parliament elections. The week

ended April 30 witnessed a collapse in India's stock markets. On Wednesday,

April 27, the Sensex fell by 213 points, wiping clean an estimated Rs.

55,000 crore of paper ''wealth''. This was the largest single-day decline

in over three years. Over the rest of the week the markets moved further

down, indicating that ''Black Wednesday'' was possibly not just a stray

blip on the trading screen. With evidence that foreign institutional

investors who were earlier pumping foreign currency into India's markets

were holding back, the rupee too witnessed a reversal of the rise that

excess dollar supplies had been resulting in.

There is unanimity among ''analysts'' of the factor driving the downturn:

news from the exit polls – the most ''scientific'' of available predictions

– that the NDA is unlikely to win a majority in the elections, which

may throw up a hung Parliament. In the run up to the elections, India's

''upper crust'' – consisting of ''the markets'', the media and large

sections of the urban middle class - had convinced itself that the results

of the elections were a forgone conclusion: the NDA would form the government;

only the margin of victory was a matter for debate. The initial opinion

polls only confirmed this belief. It is therefore not surprising that

the results of the exit polls at the end of two rounds of voting came

as a shock, marginally reversing the rupee's decline.

While this provided the RBI some respite in its increasingly difficult

task of managing the rupee, the development raises a new spectre. If

just the possibility of a fractured election result could set off a

collapse in the market and a slide in the rupee, the developments that

led to India's strong foreign exchange reserve position seem to have

increased its vulnerability as well. Investor confidence seems easy

to shake and if shaken its effects could be dramatic.

What

is noteworthy is the quick response to the exit poll results of the

market, which declared its displeasure with actions that not only erode

the wealth of its own constituents but, through their impact on credit

and foreign exchange markets, threaten a crisis in India's liberalized

financial sector. Market developments over the week ended April 30th

cannot be explained by the stray action of a few unhappy and/or nervous

investors. The herd instinct, so typical of financial markets and especially

of foreign institutional investors, has resulted in concerted action

that threatens a sharp decline. And in India's markets, which are neither

wide nor deep, a small herd can make a big difference.

On

the surface, an early correction of the baseless expectations of a few

financial investors should not be cause for worry. Few can demonstrate

that India's till-quite-recently inactive financial markets drive the

economy. However, the problem is that the crises that such changed expectations

resulted in elsewhere in East Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe and

Turkey show that they tend to damage the real economy as well. Moreover,

when the crisis of finance becomes a crisis of the real economy, its

burden falls disproportionately on the poor and the lower middle classes,

even though they do not participate in or often are not even conscious

of the workings of financial markets. Having invited foreign financial

investors into their economies, countries find that ignoring their sentiments

and/or closing the door on them when they retreat, involves painful

adjustments that the people, and therefore democratic governments, find

hard to face up to.

Thus, India seems to have a double problem on its balance of payments.

Net foreign exchange inflows are a problem because they threaten an

appreciation of the currency and a decline in exports. Foreign exchange

outflows are a problem because they seem to result from even non-economic

factors, and could cumulate into a crisis if they trigger a cycle of

unfulfilled expectations. The only redeeming feature is the high level

of India's reserves, which gives it space for manoeuvre.

The question is really the form these manoeuvres should take. Clearly

mere open market intervention to neutralize the effects of excess foreign

currency supply is inadequate. What needs to be looked at is the possibility

of managing net foreign currency flows themselves. An examination of

the balance of payments offers some pointers on what needs to be done

in this regard.

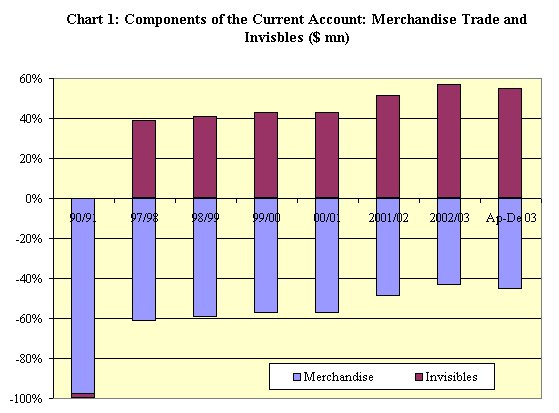

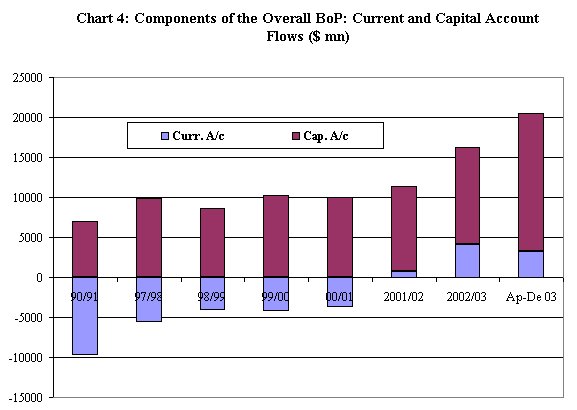

The pressure on the rupee leading to its appreciation, which is affecting

export competitiveness adversely, arises because India, which has recorded

a current account surplus since financial year 2001-02 (Chart 4), has

encouraged and attracted large inflows on its capital account. India's

current account surplus, we must note, is not a reflection of its strong

trade performance. Rather, as Chart 1 shows, it is because net inflows

under what is called the ''invisibles'' head of the current account

of the balance of payments have been more than adequate to finance a

large and recently rising merchandise trade deficit.

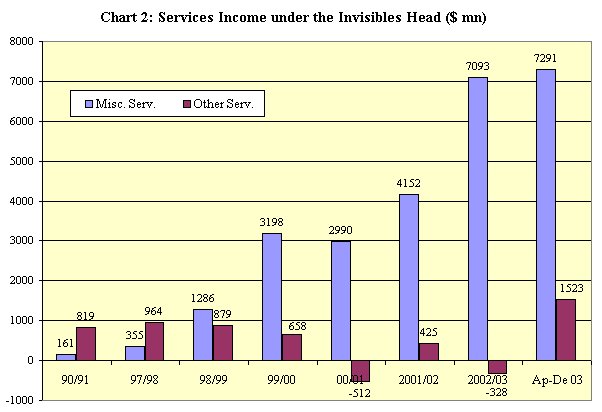

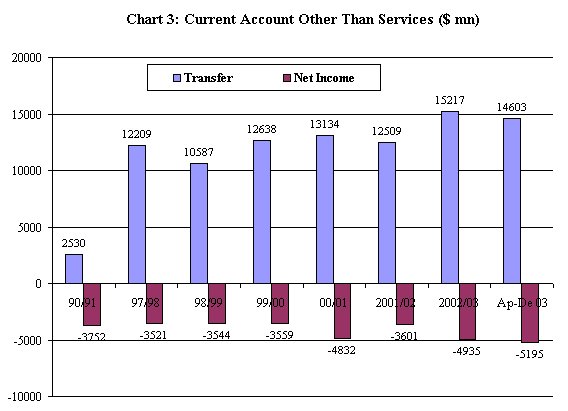

The principal sources of current account inflows have been buoyant remittance

flows, captured under the ''Transfers'' head, and inflows on account

of ''software services'' captured under the ''Miscellaneous Services''

head (Charts 2 and 3). That is, transfers made by Indian workers abroad,

either on short or long-term contracts and software service exports,

have helped overcome the adverse balance of payments consequences of

India's lack of competitiveness reflected in a large trade deficit.

Inflows on account of software services rose from $5.75 billion in 2000-01

to $6.88 billion in 2001-02, $8.86 billion in 2002-03 and $9.09 billion

over the first nine months of 2003-04, while private transfers (mainly

remittances) touched $15.2 billion in 2002-03 and $14.6 billion during

April-December 2003, after having fallen from $13.1 billion to $12.5

billion between 2000-01 and 2001-02. In an intensification of this trend,

during the first nine months of the recently ended financial year 2003-04,

net inflows on account of invisibles was, at $18.22 billion, well above

the $15 billion deficit on the trade account.

Even

while India's current account was relatively healthy on account of the

foreign exchange largesse of Indian workers abroad and the software

services boom, the country's liberalized capital markets have attracted

large inflows of capital amounting to a net sum of $10.57 billion in

2001-02, $12.11 billion in 2002-03 and a massive $17.31 billion during

the first nine months of 2003-04 (Chart 4). Expectations are that, because

of huge portfolio capital inflows during the last three months of 2003-04

encouraged by the government's privatization drive, net capital account

inflows during 2003-04 will be in excess of $20 billion.

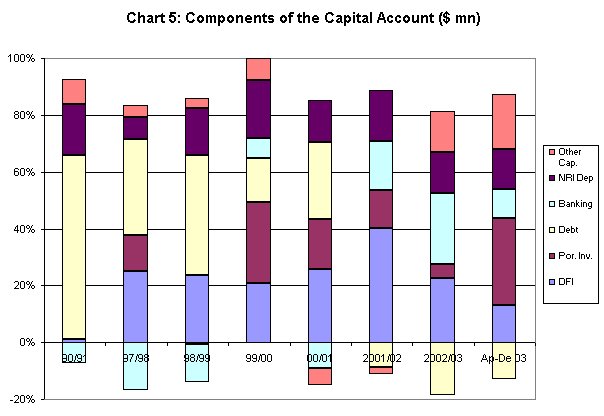

There are two issues that arise in this context. The first relates to the nature of the capital inflows during these years. The second relates to the implications of these inflows for the value of the rupee under India's liberalized exchange rate management system. Three kinds of inflows have dominated the capital account (Chart 5). An early and important source of inflow during the years of financial liberalization has been in the form of NRI deposits in lucrative, repatriable foreign currency accounts. On a net basis, such inflows accounted for $2.32 billion, $2.75 billion, $2.98 billion and $3.5 billion respectively in 2000-01, 2000-02, 2002-03 and April-December 2003, respectively. They reflect the attempt by richer non-residents to exploit arbitrage opportunities offered by the higher (relative to international rates) interest rates on repatriable, non-resident, foreign exchange accounts, to earn relatively easy surpluses.

A

second important source of capital inflows has been portfolio capital

flows, reflecting investments by foreign bodies, especially foreign

institutional investors, in India's stock and debt markets, encouraged

more recently by the disinvestment of shares in profitable public sector

undertakings. On a net basis, such inflows had fallen from $2.8 billion

in 2000-01 to $2.0 billion in 2001-02 and just $979 million in 2002-03,

but rose sharply to $7.6 billion in the first nine months of 2003-04.

As compared with this, net foreign direct investment which rose from

$4.0 billion in 2000-01 to $6.1 billion in 2001-02 fell to 4.7 billion

in 2002-03 and $3.2 billion during April-December 2003.

The third important source of capital was a financial liberalization-induced

increase in the net liabilities of commercial banks (other than in the

form of NRI deposits), which rose from a negative $1.43 billion in 2000-01

to $2.63 billion in 2001-02, $5.15 billion in 2002-03 and $2.56 billion

during April-December 2003. This is possibly explained by the expansion

of the operations of international banks in the country.

In sum, capital inflows that create new capacities either in manufacturing

or in the infrastructural sectors have been limited. Much of the capital

inflow has consisted of financial investments that expect to earn higher

annual returns than available in international markets or obtain windfall

gains from the appreciation of the value of such investments, as has

recently been witnessed in India's stock markets.

Given the determination of the exchange rate of the rupee by supply

and demand conditions in the market, this large inflow of foreign capital

in the context of a current account surplus was bound to exert an upward

pressure on the rupee. When inflows contribute to an appreciation of

the rupee, foreign investors also gain from the larger pay off in foreign

currency that any given return in rupees involves. This tends to increase

the volume of inflows. The real losers are exporters, on the one hand,

who find that the foreign exchange prices of their products are rising,

eroding their competitiveness, and domestic producers, on the other,

who find that the prices of competing imports are falling or rising

less that their own costs of production.

If the government wants to manage these capital inflows, it needs to

control inflows on account of NRI deposits, portfolio flows and banking,

all of which are the results of excessive financial liberalization,

do not contribute to enhancing productive investment, offer extremely

high returns that imply a net foreign exchange loss to the country when

matched by the low returns obtained on accumulated reserves, and are

extremely footloose in character. India's current account position is

such that it does not need large capital inflows for a comfortable balance

of payments. In particular, it does not need inflows that increase financial

vulnerability without contributing to any increase in productive investment

or exports. By doing away with the differential in interest rates offered

on non-resident external accounts and international interest rates,

the central bank has taken the first step forward. It must now go further.

©

MACROSCAN 2004