Themes > Features

9.05.2005

China's Extraordinary Export Boom

C.P. Chandrasekhar and

Jayati Ghosh

The

story of the expansion of China's exports is a remarkable one by any

standards. In 1978, China's exports were valued at around $20 billion,

and its rank among world exporters was 32nd. Since then, exports have

grown at an average annual rate of 30 per cent, such that in 2004 China

overtook Japan to become the world's third largest exporter, with exports

of nearly $600 billion.

In

2005, export growth has continued unabated, with even more breathtaking

increases recorded in the first quarter of this year. Exports grew by

more than 35 per cent compared to the same period last year, while import

growth slowed down to 15 per cent. As a result, the Chinese economy

posted a trade surplus of $16.6 billion, compared to an overall trade

deficit of $8.4 billion in the first quarter of 2004.

This

extraordinary growth has already given rise to backlash, especially

in the United States, where protectionist pressures and anti-Chinese

sentiments are on the rise. There have been calls for China to revalue

upwards its currency the yuan (or RenMinBi), which is currently pegged

at 8.28 per US dollar, not only from the US administration, but from

the OECD, the G-7, and the IMF.

What is the story behind this apparently unstoppable export growth?

Many observers have attributed this to the benefits of international

economic integration, which is why the Chinese economy is typically

cited as the great success story of globalisation. There is no doubt

that such integration has played an important role, but the point to

remember when analysing the Chinese experience is that this integration

has not been purely market-led, but has been closely monitored, regulated

and indeed controlled by the state.

This is clearly evident from a look at the external trade policy regimes

in China, which have gone through several major phases. For two decades

after Government Administration Council adopted the Interim Regulations

on Foreign Trade Management in 1950, China's trade was based on complete

state monopoly and dominated by trade with the former Soviet Union and

other Eastern European countries. From 1979, along with various internal

reforms especially related to the peasant contract system in agriculture,

there was some opening up of trade.

From 1979 to 1987, there was a process of delegating authority with

respect to foreign trade to lower levels and decentralising the highly

concentrated planning management system. National purchase and allocation

plans were replaced instructive plans with market regulation and implementing

import and export licenses and a quota system. The pattern of trade

was also diversified to include compensation trade, processing with

supplied materials, trade on commission basis, border trade, local trade,

small-deal trade, processing and assembling with imported materials,

processing for export, chartering and leasing trade.

Between 1988 and 1990, foreign trade subsidies were frozen and a contract

responsibility system in foreign trade was implemented. From 1991 to

1993, the foreign exchange mechanism was readjusted and a double-track

exchange rate was adopted. Foreign trade enterprises (still dominantly

State Owned Enterprises) were allowed to retain part of their foreign

exchange earnings, but all financial subsidies to them were stopped

and they were made to take on the responsibility for their own profits

and losses.

In 1994, the unification of the dual rates in foreign exchange and adopting

a unified floating exchange rate for Renminbi on the basis of market

need and supply effectively meant a substantial devaluation of the RenMinBi.

At the same time, the practice of allowing foreign trade enterprises

to retain part of their foreign exchange earnings was abolished. The

tax refund system for exports was implemented, and the range of import

and export quotas and licenses was substantially cut.

On July 1, 1994, the ''Foreign Trade Law'' was officially put into effect,

which stated that China practices a unified foreign trade system and,

while giving appropriate protection to domestic enterprises, adopts

such internationally conventional anti-dumping, anti-subsidy and guarantee

practices. Controls were lifted over more than 90 per cent of export

commodities, where market prices were to be dominant, and a bidding

system was introduced for some important export commodities.

The WTO Accession Agreement of 2002 marked a new phase of intensified

liberalisation of trade, with China making sweeping commitments to reduce

quota controls, tariffs and so on especially with respect to agricultural

products. Nevertheless, despite the apparent drastic trade reforms,

the Chinese government retains substantial control over trade through

two important levers.

First, nearly half of all exports are still accounted for by State Owned

Enterprises, although the share of foreign owned enterprises has been

increasing recently. Second, control over the banking system and the

ability to direct and regulate the allocation of credit has been the

most important instrument both of macroeconomic control and of direction

of investment and production, which has had direct effects on both exports

and imports. The recent deceleration in import growth, for example,

is a clear result of the controls on credit implemented by the Chinese

authorities on fears of overheating in the economy.

These various phases have also been associated with different degrees

of integration into the world economy, based on indicators like trade

dependence in GDP. The share of total trade (imports and exports) in

GDP rose in a stable fashion from 9 per cent in 1978 to 25 per cent

in 1989. In the 1990s, influenced by the dual impact of the RMB's devaluation

and the accelerated growth of GDP value counted in terms of RMB, China's

foreign trade dependence ratio experienced great fluctuations. From

2000, the rise in trade shares of GDP has been very rapid, going up

from 43.8 per cent in 2000 to 60 per cent in 2003 to 70 per cent in

2004.

Despite the past experience of major exporters of the 20th century like

Japan and South Korea, this experience is historically unique in its

rapidity and extent, since no other country has been through such a

massive increase in trade shares in such a short time. This can be attributed

to a number of special features of China's current trade, which is particularly

based on the globally integrated production which is a relatively new

feature of the world economy.

The proportion of processing trade is rather high in the makeup of China's

foreign trade, which accounts for high imports being associated with

high exports. Further, the Chinese expansion is still dominantly driven

by manufacturing, and the tertiary sector still accounts for only one-third

of GDP.

It is also true that China's GDP has probably to some extent been devalued

because of statistics reasons. The overall GDP value of the country

is lower than the summation of the production values of all regions,

which suggests that the aggregate GDP data could be underestimates.

The sums of the regional GDP values were 8.7, 9.7, 11.7 and 15.6 per

cent higher respectively than the overall GDP values in the years from

2000 to 2003. This would make the trade share of GDP appear to be higher

than it actually is.

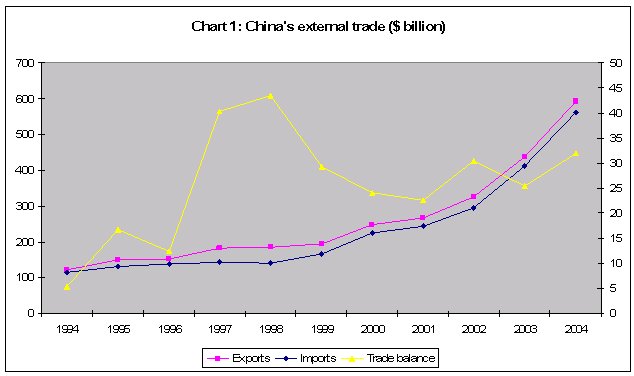

This is the context in which the recent trends in China's trade have

to be viewed. Chart 1 shows the pattern of overall trade since 1994.

It is evident that both exports and imports have been rising rapidly,

but the trade surplus (on the right axis) has been relatively moderate

and indeed has declined from its peak of 1997. The perception of overvaluation

of the yuan is not justified from the point of the of the overall trade

balance, which is currently showing a surplus of only around $32 billion,

or only 2.3 per cent of GDP, which is hardly large by international

standards.

What is of greater interest is the pattern of recent trade. The conventional view is that it has been driven by export of textiles and clothing, after the withdrawal of MFA quotas and the entry of China in the WTO. But Table 1, which indicates the top ten categories of export, suggests that apparel or garments has been only one of the factors behind the big export push. Toys, which was the other great export success of the 1990s, is also relatively less important in recent exports, which have been dominantly driven by capital goods.

Table

1: Top ten exports of China |

|||||||||

Commodity

Description |

2003

($ mn) |

2004

($ mn) |

Per

cent change |

||||||

Electrical

machinery & equipment |

88,977.6 |

129,663.7 |

45.8 |

||||||

Power

generation equipment |

83,468.9 |

118,149.3 |

41.7 |

||||||

Apparel |

45,759.2 |

54,783.6 |

19.7 |

||||||

Iron

& steel |

12,864.8 |

25,216.4 |

96.0 |

||||||

Furniture

& bedding |

12,895.5 |

17,318.6 |

29.1 |

||||||

Optics

& medical equipment |

10,564.3 |

16,221.0 |

53.6 |

||||||

Footwear

& parts thereof |

12,955.0 |

15,203.2 |

17.4 |

||||||

Toys

& games |

13,279.9 |

15,089.2 |

13.6 |

||||||

| Mineral fuel & oil | 11,110.2 |

14,475.7 |

30.2 |

||||||

| Inorganic & organic chemicals | 10,734.8 |

13,937.6 |

29.8 |

||||||

This

indicates some shifts in trade pattern. Toys, clothing, furniture and

television sets have dominated Chinese exports for years, but now newer

products like portable electric lamps and even radio navigation equipment

are now being shipped in growing quantities to countries ranging from

Britain and Spain to Brazil and Indonesia. At the same time, China is

becoming a large exporter of industrial commodities like steel and chemicals,

importing fewer cars and less heavy machinery as Chinese companies and

multinationals manufacture more of these in China.

These changes are reflected in imports, which are again dominated by

capital goods rather than raw materials. Even though China became the

most significant marginal consumer in the world oil market in 2004,

oil imports are only the third largest element in the total import bill,

as Table 2 indicates.

Table

2: Top ten imports into China |

|||||||||

Commodity

Description |

2003 |

2004 |

%

change |

||||||

Electrical

machinery & equipment |

103,925.9 |

142,073.6 |

36.7 |

||||||

Power

generation equipment |

71,500.2 |

91,631.6 |

28.2 |

||||||

Mineral

fuel & oil |

29,272.5 |

48,036.6 |

64.2 |

||||||

Optical

& medical equipment |

25,137.5 |

40,154.9 |

59.8 |

||||||

Iron

& steel |

25,596.9 |

28,387.1 |

10.9 |

||||||

Plastics

& articles thereof |

21,032.6 |

28,060.1 |

33.4 |

||||||

Inorganic

& organic chemicals |

18,736.9 |

27,809.0 |

48.4 |

||||||

Ore,

slag, & ash |

7,171.9 |

17,292.7 |

141.0 |

||||||

| Vehicle & parts other than rail | 11,814.8 |

13,102.7 |

11.2 |

||||||

| Copper & articles thereof | 7,165.4 |

10,484.3 |

46.3 |

||||||

The

changes in the steel industry are perhaps the most illustrative of what

is going on. China has become the world's largest steel consumer, because

of its massive construction boom and investment in road infrastructure.

But Chinese steel production has risen even faster, as practically every

province has erected steel mills. So many of these mills produce steel

reinforcing bars, known in the industry as rebars and used in concrete

construction, that China has gone from a shortage of rebars to a glut,

and Chinese rebars are now being exported all over the world.

China became the largest foreign supplier last year of steel tubing

and casing for oil wells in the United States, another technologically

simple steel product that Chinese mills have mastered. Over all, China

remains a net importer of steel, but by a shrinking margin. In 2004,

steel imports fell 11.3 per cent, to $3.82 billion, while exports rose

389 per cent, to $2.62 billion.

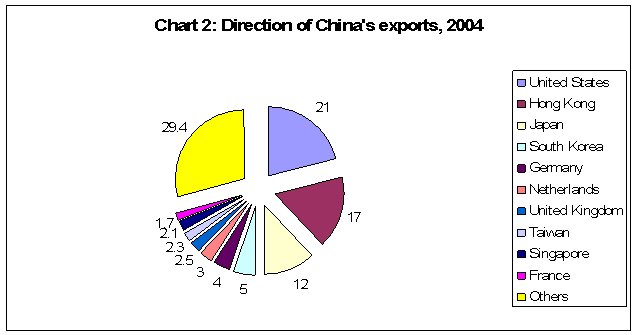

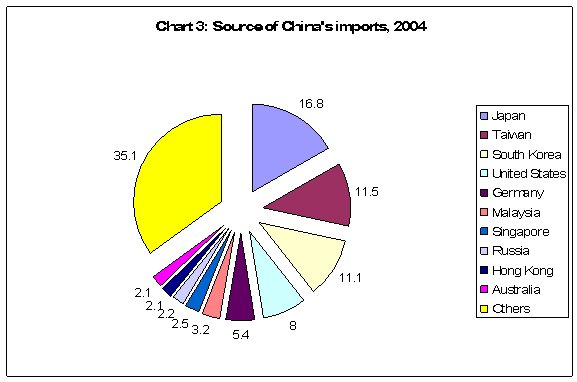

These changes are also mirrored in the direction of trade, which has

shown less dependence upon the United States in very recent times, and

more concentration of Asia. This is reflected in Charts 3 and 4, showing

the destination of exports and the source of imports respectively in

2004.

This is part of a conscious policy of the Chinese government, to diversify

trade patterns and increase interaction not only within Asia (as exemplified

by the China-ASEAN deal of late last year) but also attempts to reach

out to Latin American and African countries.

All this indicates the hard-headed and practical nature of the Chinese

economic leadership, which has so far resisted the increasingly oppressive

calls for currency revaluation and tried alternative methods like an

export tax, which it has already imposed on garments exports. Clearly,

the Chinese trade strategy is one which involves far greater and more

consistent state intervention than almost any other country, and its

current expansion must be seen in that light.

© MACROSCAN 2005