Themes > Features

29.05.2006

Explaining the Stock Market Correction

C.P. Chandrasekhar and

Jayati Ghosh

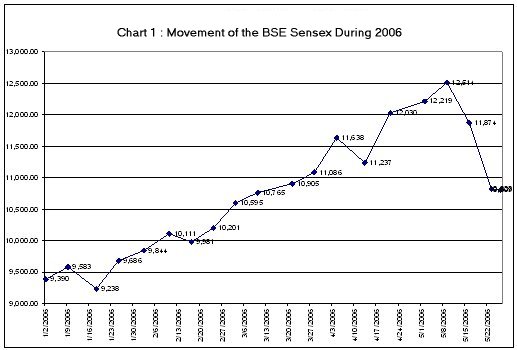

In a recently accelerated climb, the Bombay Sensex rose from 5054 on July 22, 2004 to 6017 on November 17, 2004, 7077 on June 21, 2005, 8073 on November 2, 2005, 9067 on December 9, 2005, 10082 on February 7, 2006, 11079 on March 27, 2006, 12219 on May 2, 2006 and 12435 on May 11, 2006. The implied price increase of more than 37 per cent over the last five months is indeed remarkable. The rise in the first four and a half months of 2006 alone was around 14 per cent (Chart 1).

A

reasonable assessment would have been that this rise was unsustainable

and unwarranted by actual corporate performance. A correction, therefore,

was in order and did occur in the second half of May, even if to an

inadequate extent. The Sensex fell from its May 11 peak of 12435 to

10482 on May 22, only to rise once again to 10,809 on May 26.

One response to this minor correction has been that the obstacles set

by the Left and even Sonia Gandhi to the advance of economic reform

has generated uncertainty in the markets, leading to the loss of paper

wealth which should not have been accumulated in the first place. Thus

the Wall Street Journal Europe recently (May 24, 2006) suggested that

Sonia Gandhi's ''actions as leader of the Congress Party and chairwoman

of the governing coalition are causing increasing worries among investors

as to the pace of economic reforms.'' It quotes one Indian market research

consultant, who is by no means a disinterested observer, as saying that

''the major obstacle to reform is Sonia Gandhi''. This response is in

keeping with the overall perception that liberalisation policies that

spur speculative fever of the kind seen in the markets should not be

tempered in any way, as it hurts investors and can trigger a retreat

that can be damaging.

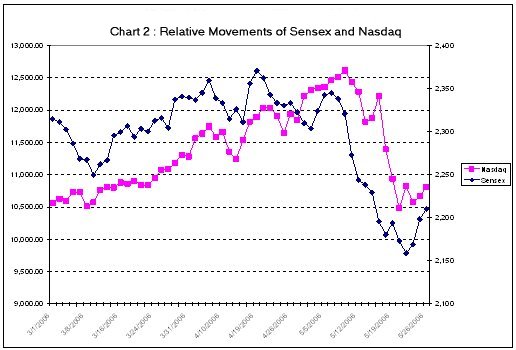

The problem with this argument is that it ignores the fact that the

May downturn was not restricted to India alone but was a global phenomenon.

As Chart 2 shows, recent movements in the Sensex have closely followed

the Nasdaq index. Further, the decline witnessed in May was not confined

to India, but affected many emerging markets, including Russia, Turkey,

Indonesia, South Korea and Taiwan.

Many

analysts have argued that this global downturn was triggered in the

first instance by expectations of a rise in US interest rates. With

GDP growth rates in the US placed at well above 5 per cent in the first

quarter of 2006, the Fed was expected to cool the economy by raising

interest rates. This was because of the perception that in a global

environment where high oil prices were already raising costs and prices,

buoyant domestic demand leading to high growth rates would also result

in inflation that the monetary authorities would be forced to contain.

In the event, the expectation of a possible rise in interest rates had

resulted in a retreat from speculative investments in equities and commodities.

The result was the downturn in stock markets, initially in the US and

then across the globe, with emerging markets like India, Russia, Turkey,

Indonesia, South Korea and Taiwan being hit hard. So when the first

revision of the preliminary estimate of GDP growth in the US during

the first quarter of 2006 released on May 25 placed the revised first-quarter

growth rate at 5.3 per cent (not 6.2 as originally expected) and news

was out that consumer spending and the US housing market was cooling,

''investors'' ostensibly heaved a sigh of relief. According to the financial

press, there would be less pressure on the Fed to raise interest rates,

allowing for a return to ''normalcy'' in markets after what would be

a mere correction and not a meltdown.

What needs to be noted is that while the figures at issue are GDP growth,

consumer spending and interest rates in the US, the market movements

being referred to are global. This is because the evidence makes clear

that market movements across the globe are now synchronised. When the

downturn occurs it is generalised worldwide, and when the recovery begins

all markets catch up. The old-fashioned idea that investors include

different markets in their portfolio to hedge their positions no more

seems true, since that is predicated on markets not moving in parallel.

One factor that accounts for the synchronisation of market movements

is that a few global players drive all markets, centralising in themselves

the funds available for investment. Since these financial entities tend

to behave in herd-like fashion, rushing into particular markets and

instruments when the going seems good and withdrawing together when

uncertainty strikes, their decisions determine the buoyancy or lack

of it in most markets.

In all the emerging markets, the downturn since the middle of May and

the collapse on May 22 were related to withdrawal of investments by

foreign investors. According to the Financial Times (May 26, 2006),

about $5 billion of foreign funds had flowed out of Asian emerging markets

over the previous week, with around three quarters coming from South

Korea and Taiwan. The other market to be afflicted badly by this syndrome

was India. By May 26 the Mumbai Sensex had fallen by as much as 16 per

cent relative to its May 11 peak. Foreign institutional investors are

estimated to have pumped in $10.7 billion into India's markets in 2005

and a further $5 billion by May 11 this year. So when they decided to

pull out around $2 billion between May 11 and May 25, a sharp downturn

ensued.

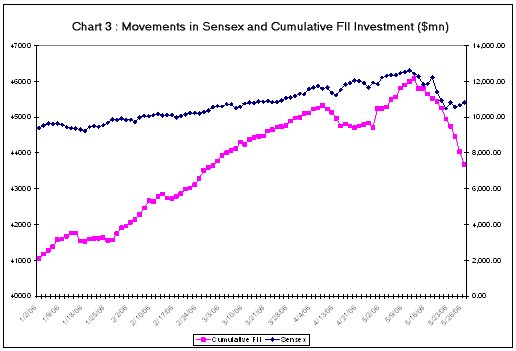

While it has been acknowledged that FII investments have been primarily

responsible for the surge in India's stock markets, it is true that

domestic investors including mutual funds have recently sought to profit

from the stock market boom. As a result while earlier cumulative FII

investments in the Indian market closely tracked movements in the Sensex,

more recently the index has tended to outstrip growth in cumulative

foreign institutional investment. But as Chart 3 shows, the FII pullout

has played a dominant role in explaining the decline in the Sensex.

This being the case, what is puzzling about recent market behaviour

is the fact that global investors have gone bearish on all markets,

resulting in the generalised downturn in global markets. In particular,

why should the danger of higher interest rates in the US weaken sentiments

in equity markets worldwide? In the past, a rise in interest rates in

the US was seen as a factor that would stimulate American capital markets

as it would result in a rush of capital into dollar denominated assets,

by improving the relative return of investments in the US.

However,

for some time now this positive relationship between US interest rates

and capital flows to the US has not held. Throughout the recent period

when US interest rates were low, dollar denominated assets were preferred

by investors as a safe haven. Capital kept pouring into the US, triggering

initially a stock market boom and, subsequently, because of their role

in keeping interest rates down, a housing market boom. It has been held

for some time now that, because the stock and housing boom inflated

the value of assets owned by Americans and therefore their level of

savings, US residents were encouraged to spend more of their current

incomes on consumption resulting in a collapse of household savings

rates to negative levels. The obverse of this trend was buoyant domestic

demand that helped sustain a creditable rate of GDP growth, despite

the leakage of demand abroad reflected in large trade and current account

deficits in the US balance of payments.

It could therefore be argued that if interest rates go up making borrowing

more expensive, the domestic consumer spending and housing boom could

be quickly reversed, resulting in a slow down of growth in the US and

a loss of faith in the strength of the US economy. To the extent that

this could adversely affect investments in US assets, the fear that

extremely high rates of growth in the US or excess speculation in the

housing markets could force the Fed to raise interest rates, is seen

as setting off shivers in stock markets as well.

The difficulty with this argument is that if it were true, then the

downturn should have been restricted to US stock markets alone. In fact,

the exit of investors from the US should have been accompanied by a

shift to other markets, which should have attracted more investments

and witnessed a boom. However, recently equity markets worldwide, including

the emerging markets, were rising when the US market was rising and

declining even more sharply, with a short lag, when US markets slumped.

This clearly makes the argument linking the downturn in the US market

to the likely adverse effects of higher interest rates on domestic demand

and growth an inadequate explanation of synchronised global trends.

One way in which the relationship between interest rate expectations

and the synchronised downturn could be explained is to trace the link

between the preceding synchronised boom in global markets and low interest

rates. If the boom, which seems increasingly to be triggered by a few

major players, was the result of debt-financed investments in shares

with already inflated values in the expectation of attractive short-term

returns, then the threat of interest rate increases could encourage

speculators to unwind their debt-financed investments, thereby triggering

a downturn. And if it is the same set of investors who are driving markets

worldwide and they are adopting similar strategies in all markets, then

the unwinding of debt-financed investments would occur in more markets

than one, resulting in the generalised downturn witnessed recently.

These developments once again raise an issue that has been a source

of controversy in the past. The US Federal Reserve and central banks

elsewhere have always been concerned about commodity-price inflation

but not asset-price inflation. The Fed has in the past been unwilling

to raise interest rates to dampen speculative price increases in stock

and even real asset markets, while holding that its principal role is

to rein in inflation. The indication that the threat of an interest

rate hike as a result of developments in commodity market triggers a

downturn in equity markets, makes clear that central banks must play

a role in using the interest rate to curb price increases in asset markets

as well in order to prevent a speculative bubble that can burst with

damaging consequences for real economies.

Closer home, the above developments make it clear that all talk attributing

stock market volatility in India to the inadequacy of ''reform'' or

the obstacles to reform set by Sonia Gandhi or the Left is that much

nonsense. The Indian market is driven by global decisions, which in

turn are determined by the speculative activities of key investors the

government seeks to attract. Once we recognise that financial volatility

is the result of the speculative behaviour of these firms, measures

to reduce the presence and influence of these investors seem to be the

need of the day. If either the Sonia Gandhi camp in the Congress or

the Left is calling for caution and holding back policies that feed

such speculation, they are only doing the nation good.

© MACROSCAN 2006