Themes > Features

10.05.2009

The International Transmission of Fragility

The

April 2009 edition of the IMF's Global Financial Stability Report is

categorical. Global financial stability has deteriorated further since

its last assessments in October and January, with conditions worsening

more in emerging markets in recent months. Within emerging markets,

while European countries have been affected most, the problem is acute

elsewhere as well with some countries in Asia, which had emerged the

growth pole in the world economy, being impacted severely. Thus even

a country like South Korea, which is seen as having recovered substantially

from the damage inflicted by the 1997-98 crisis, is now experiencing

a crisis in its financial sector with feedback effects on the real economy.

Examining this Asian face of the crisis does offer some important lessons-once

again.

There are many ways in which developing countries have been affected

by what began as a developed country crisis. But there are two which

are seen as being of particular relevance. One is through the effect

of the global slowdown on their exports. This is in some sense unavoidable,

though this effect would differ across countries depending on the degree

to which growth in individual countries is dependent on exports, especially

to developed country markets, and on the degree to which countries can

redirect growth away from dependence on export markets to dependence

on domestic demand. The second is because of a sudden reversal of capital

inflows, with attendant effects on reserves, currency values and liquidity.

As the IMF puts it: ''The deleveraging process is curtailing capital

flows to emerging markets. On balance, emerging markets could see net

private capital outflows in 2009 with slim chances of a recovery in

2010 and 2011.''

The outflows, the IMF estimates, can be substantial. Net private capital

flows to countries the IMF identifies as emerging markets peaked at

4.45 per cent of their GDP. This is estimated to fall to 1.34 in 2008

and a negative 0.15 per cent in 2009. Much of this decline and reversal

would be on account of portfolio and ''other'' investment, which are

estimated to be negative in both years, whereas the flow of FDI is expected

to be positive, though smaller. This is not surprising since it is to

be expected that the impact would be greater on hot money flows, as

the IMF suggests. Heavily leveraged firms faced with redemption pressures,

such as hedge funds, have played an important role, with nearly one-third

of the $23 billion in assets under the management of such funds in emerging

markets having been repatriated in the fourth quarter of 2008. This

process of ''deleveraging'' is of course a reflection of the need of

international banks and financial firms to withdraw capital from emerging

market to meet demands at home.

But it has damaging effects in emerging market countries. Stock markets

have collapsed, and currencies are depreciating sharply. When the exit

of capital results in a depreciation of the local currency, corporations

that have accumulated foreign exchange liabilities in the recent past

find that declining revenues and higher local currency costs of acquiring

foreign exchange are squeezing profits, delivering losses and even threatening

bankruptcies. Banks that have lent to these corporations are recording

increases in non-performing assets and are cutting back on credit provision.

And the flight of capital implies that consumers and investors who financed

large consumption and investment expenditures with credit are being

forced to cut back worsening the shrinkage of demand. This is a vicious

cycle that drives the downturn in emerging markets, some of which, according

to the IMF, have become the focus of the crisis in recent months.

It bears noting that this set of developments linked to capital reversal

is surprising given the received mainstream wisdom on the source of

the global imbalances that led up to the current crisis. Developing

countries, it was argued, especially developing countries in Asia, had

turned cautious after their experience with the crises in 1997 and after,

and were therefore holding the foreign exchange they earned from net

exports as reserves. The resulting global savings glut was accompanied

by a flow of capital to the developed countries, particularly the United

States, financing not just the current account deficit but also the

boom in stock, housing and commodity markets in that country. It was

because the resultant excess spending that generated the upswing in

goods and asset markets in the US could not be sustained for ever that

the boom had to unwind through a process that inexorably led to a recession.

The first problem with this argument is that it misses the fact that

in the case of most developing countries, including many of the exceptional

performers in Asia (barring cases like China, where net exports were

indeed important), the accumulation of foreign reserves was the result

of the inflow of capital. Second, this inflow of capital took the form

of a supply-side surge driven by financial developments in the developed

countries with financial institutions in those countries being the ''source''

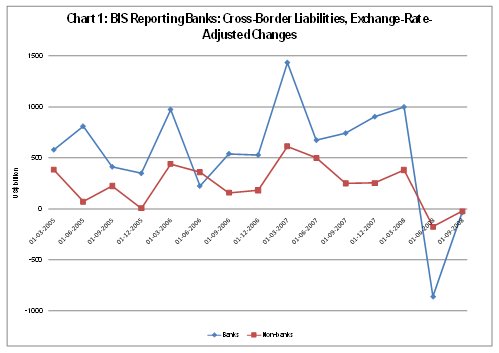

of capital. As Chart 1 indicates, the increases in the Cross-Border

Liabilities of Banks reporting to the Bank of International Settlements

were substantial since early 2005 (even after adjusting for exchange

rate changes), with a significant acceleration of such changes between

mid-2006 and the first quarter of 2008. An examination of the country-wise

break of the location of banks with such cross-border liabilities shows

that most of these banks were located in the developed countries and

were accumulating substantial liabilities in developing countries as

well.

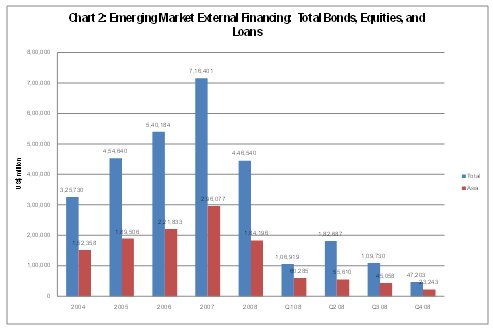

In

fact, if we take total external financing in the form of bond financing,

equity financing and syndicated loans, there was a significant increase

in such financing between 2004 and 2007 in countries identified as emerging

markets by the IMF. Further, the share of Asian emerging markets (EMs)

was substantial, despite the evidence that European EMs were receiving

a large share of such financing (Chart 2). It is only in 2008, when

the crisis had set in that we begin to see a decline in flows and that

decline was sharp in the last two quarters of 2008. The point to note

is that the increased inflow prior to 2008 was not because of any special

measures adopted by these countries. Many of them had begun liberalizing

their rules with regard to capital inflows in the early 1990s and had

gone the distance by the time of the 1997 crisis, after which capital

flows to developing countries in Asia were curtailed. The resurgence

of inflows after 2004 was not specifically driven by any new policy

changes in the recipient countries, but by a push generated by excess

liquidity in the source countries. The error on the part of the emerging

market countries was that they had not imposed restrictions on capital

inflows after the 1997 crisis, making them vulnerable to surges in capital

inflows followed by reversals, or to boom-bust cycles of the kind that

preceded 1997.

The point to note is that liberalization did not offer any guarantee

of capital inflows either in normal times or in times of irrational

exuberance. Capital inflows do not necessarily rise sharply immediately

after liberalization nor do all countries attract inflows once they

liberalize. Thus during the period of the global capital surge beginning

2004, a few developing countries in Asia accounted for an overwhelming

share of capital flows to emerging markets in the region. Table 1 shows

that the 7 top emerging market recipients of capital inflows received

between 85 and 95 per cent of the flows into emerging Asia.

Table

1: Share of Top Seven in Asian Emerging Market External Financing |

|||||||||

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

Q1

08 |

Q2

08 |

Q3

08 |

Q4

08 |

|

China |

16.8 |

20.5 |

22.6 |

25.2 |

15.8 |

19.5 |

15.1 |

15.9 |

7.5 |

Hong

Kong SAR |

12.7 |

10.6 |

11.6 |

7.9 |

8.4 |

4.3 |

8.9 |

14.1 |

6.4 |

India |

8.7 |

11.4 |

13.3 |

19.6 |

20.2 |

25.7 |

14.8 |

18.3 |

22.6 |

Indonesia |

2.7 |

2.7 |

3.8 |

2.7 |

7.5 |

6.6 |

10.9 |

3.5 |

9.4 |

Korea |

20.4 |

25.2 |

17.4 |

20.1 |

18.6 |

19.4 |

25.7 |

10.1 |

16.0 |

Singapore |

7.8 |

7.7 |

8.9 |

6.6 |

11.1 |

9.8 |

11.7 |

13.9 |

7.6 |

Taiwan

Province of China |

17.4 |

10.1 |

10.0 |

8.2 |

9.8 |

10.5 |

5.6 |

11.2 |

15.2 |

| Total | 86.6 |

88.1 |

87.6 |

90.4 |

91.3 |

95.7 |

92.8 |

86.9 |

84.8 |

The

crisis in some of these countries is a result of the reduction of these

inflows to some of these ''beneficiaries'' of the capital inflow surge.

What is noteworthy is that the decline in aggregate external market

financing has been accompanied by a sharp fall in mobilization of finance

through bond financing, while the fall has been lower in the case of

equity financing and syndicated borrowing (Tables 2, 3 and 4). In fact,

the relative share of syndicated loans in total private external financing

has risen quite significantly across leading emerging markets in Asia.

Clearly, emerging market paper was less attractive and a rising share

of flows that were occurring were the result of dedicated effort to

syndicate loans and ensure some capital inflow.

The evidence that a reversal of flows has been damaging, even in countries

that were performing well with strong reserves and reasonably good macroeconomic

conditions, demonstrates once again the fragility associated with excessive

dependence on external capital inflows. In the circumstance, the case

for imposing controls on inflows to reduce the vulnerability that results

from global as opposed to domestic developments is strong. But as in

1997, it is unclear today whether countries would absorb the lessons

of the current crisis and do the needful. And if a relatively stronger

Asia does not, it is unlikely that developing countries elsewhere would

do so.

Table

2: Share of Top Seven in Asian Emerging Market External Financing:

Bond Issuance |

|||||||||

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

Q1

08 |

Q2

08 |

Q3

08 |

Q4

08 |

|

China |

17.0 |

9.9 |

2.2 |

2.9 |

7.1 |

0.0 |

3.6 |

24.5 |

0.0 |

Hong

Kong SAR |

17.2 |

23.1 |

14.0 |

22.0 |

15.9 |

17.1 |

16.5 |

18.4 |

1.5 |

India |

24.1 |

9.8 |

9.0 |

13.0 |

3.8 |

1.0 |

15.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Indonesia |

33.1 |

54.2 |

23.7 |

21.6 |

30.5 |

50.5 |

36.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Korea |

57.1 |

37.7 |

47.4 |

37.4 |

43.0 |

27.6 |

53.0 |

55.4 |

38.1 |

Singapore |

47.9 |

29.2 |

24.1 |

22.9 |

10.3 |

5.4 |

27.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Taiwan

Province of China |

1.7 |

4.2 |

1.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Table

3: Share of Top Seven in Asian Emerging Market External Financing:

Equity Issuance |

|||||||||

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

Q1

08 |

Q2

08 |

Q3

08 |

Q4

08 |

|

China |

53.6 |

59.8 |

81.0 |

64.0 |

43.9 |

40.8 |

60.4 |

22.6 |

72.8 |

Hong

Kong SAR |

19.2 |

20.4 |

23.6 |

24.3 |

13.5 |

4.4 |

36.1 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

India |

37.8 |

39.6 |

37.3 |

32.9 |

15.8 |

29.8 |

12.8 |

2.1 |

0.5 |

Indonesia |

20.6 |

25.7 |

8.0 |

33.0 |

16.9 |

6.8 |

27.7 |

24.1 |

0.0 |

Korea |

17.1 |

26.4 |

18.9 |

10.3 |

6.5 |

9.8 |

5.1 |

0.0 |

9.7 |

Singapore |

21.8 |

27.5 |

22.2 |

21.4 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

Taiwan

Province of China |

12.8 |

37.6 |

16.0 |

19.9 |

4.7 |

1.0 |

2.6 |

13.9 |

0.0 |

Table

4: Share of Top Seven in Asian Emerging Market External Financing:

Syndicated Loans |

|||||||||

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

Q1

08 |

Q2

08 |

Q3

08 |

Q4

08 |

|

China |

29.4 |

30.3 |

16.8 |

33.1 |

49.0 |

59.2 |

36.0 |

52.9 |

27.2 |

Hong

Kong SAR |

63.6 |

56.5 |

62.4 |

53.7 |

70.5 |

78.5 |

47.4 |

79.4 |

96.0 |

India |

38.2 |

50.6 |

53.8 |

54.1 |

80.4 |

69.2 |

72.0 |

97.9 |

99.5 |

Indonesia |

46.2 |

20.1 |

68.3 |

45.4 |

52.6 |

42.7 |

36.0 |

75.9 |

100.0 |

Korea |

25.7 |

35.9 |

33.7 |

52.3 |

50.5 |

62.6 |

41.9 |

44.6 |

52.2 |

Singapore |

30.3 |

43.3 |

53.7 |

55.7 |

89.6 |

94.6 |

72.5 |

100.0 |

98.5 |

Taiwan

Province of China |

85.5 |

58.2 |

82.7 |

80.1 |

95.3 |

99.0 |

97.3 |

86.1 |

100.0 |

©

MACROSCAN 2009