| |

|

|

|

|

Revisiting

Capital Flows* |

| |

| May

4th 2011, C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh |

|

A

striking feature of the recent global financial crisis

and its aftermath is the behaviour of private international

capital flows, especially to emerging markets. Prior

to the crisis, in the years after 2003, a number of

analysts had noted that the world was witnessing a

surge in capital flows to emerging markets. These

flows, relative to GDP, were comparable in magnitude

to levels recorded in the period immediately preceding

the financial crisis in Southeast Asia in 1997. They

were also focused on a few developing countries, which

were facing difficulties managing these flows so as

to stabilise exchange rates and retain control over

monetary policy. They also included a significant

volume of debt-creating flows, besides other forms

of portfolio flows.

Interestingly, these developments did not, as in 1997,

lead up to widespread financial and currency crisis

originating in emerging markets, as happened in 1997.

However, the risks involved in attracting these kinds

of flows were reflected in the way the financial crisis

of 2008 in the developed countries affected emerging

markets. Financial firms from the developed world,

incurring huge losses during the crisis in their countries

of origin, chose to book profits and exit from the

emerging markets, in order to cover losses and/or

meet commitments at home. In the event, the crisis

led to a transition from a situation of large inflows

to emerging markets to one of large outflows, reducing

reserves, adversely affecting currency values and

creating in some contexts a liquidity crunch.

Given the legacy of inflows and the consequent reserve

accumulation, this, however, was to be expected. What

has been surprising is the speed with which this scenario

once again transformed itself, with developing countries

very quickly finding themselves the target of capital

inflows of magnitudes that are quickly approaching

those observed during the capital surge. As the IMF

noted in the latest (April 2011) edition of its World

Economic Outlook: ''For many EMEs, net flows in the

first three quarters of 2010 had already outstripped

the averages reached during 2004–07,'' though they

were still below their pre-crisis highs.

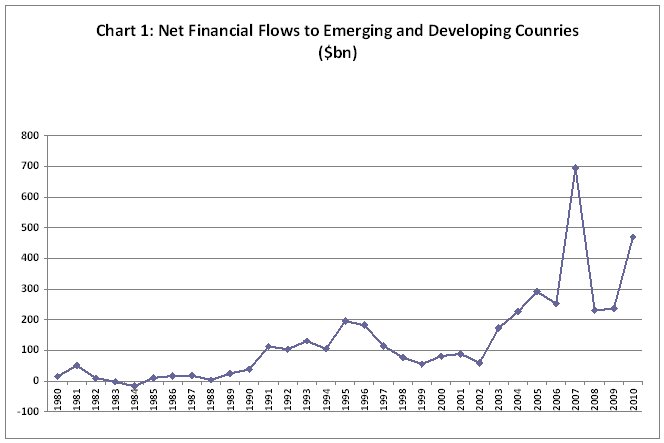

One implication of the quick restoration of the capital

inflow surge is the fact that, in the medium-term,

net capital inflows into developing countries in general,

and emerging markets in particular, has become much

more volatile. As Chart 1 shows, net capital flows

which were small though the 1980s, rose significantly

during 1991-96, only to decline after the 1997 crisis

to touch close to early-1990s levels by the end of

the decade. But the amplitude of these fluctuations

in capital inflows was small when compared with what

has followed since, with the surge between 2002 and

2007 being substantially greater, the collapse in

2008 much sharper and the recovery in 2010 much quicker

and stronger.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

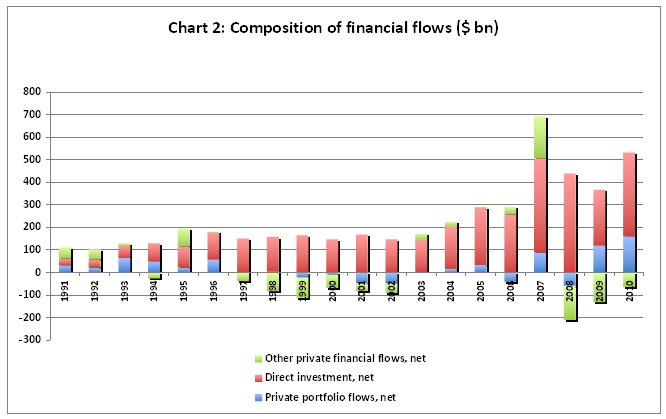

When

we examine the composition of flows we find that volatility

is substantial in two kinds of capital flows: ''private

portfolio flows'' and ''other private'' flows, with

the latter including debt (Chart 2). There has been

much less volatility in the case of direct investment

flows. However, in recent years the size of non-direct

investment flows has been substantial enough to provide

much cause for concern. Further, besides the fact that

direct investment flows are differentially distributed

across countries (with China taking a large share),

the definition of direct investment is such that the

figure includes a large chunk of portfolio flows. The

magnitude of the problem is, therefore, still large.

Does this increase in volatility during the decade of

the 2000s speak of changes in the factors driving and

motivating capital flows to emerging markets? The IMF

in its World Economic Outlook does seem to think so,

though the argument is not formulated explicitly. In

its analysis of long-term trends in capital flows the

IMF does link the volatility in flows to the role of

monetary conditions (and by implication monetary policy)

in the developed countries, especially the US, in influencing

those flows.

As the WEO puts it, ''Historically, net flows to EMEs

have tended to be higher under low global interest rates,

(and) low global risk aversion,'' though this assessment

is tempered with references to the importance of domestic

factors. Shorn of jargon, there appears to be two arguments

being advanced here. The first is that capital flows

to emerging markets are largely influenced by factors

from the supply-side, facilitated no doubt by easy entry

conditions into these economies resulting from financial

liberalisation. The second is that easy monetary policies

in the developed countries has encouraged and driven

capital flows to developing countries. This is because

easy and larger access to liquidity encourages investment

abroad, while lower interest rates promote the ''carry-trade'',

where investors borrow in dollars to invest in emerging

markets and earn higher financial returns, based on

the expectation that exchange rate changes would not

reduce or neutralise the differential in returns. Needless

to say, when monetary policy in the developed countries

is tightened, the differential falls and capital flows

can slow down and even reverse themselves.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

The evidence clearly supports such a view. The period

of the capital surge prior to 2007 was one where the

Federal Reserve in the US, for example, adopted an easy

money policy, involving large infusion of liquidity

and low interest rates. While this was aimed at spurring

credit-financed domestic demand, especially for housing,

so as to sustain growth, it also encouraged financial

firms to invest in lucrative markets abroad. Flows reversed

themselves when the losses and the uncertainty resulting

from the sub-prime crisis and its aftermath resulted

in a credit crunch. Finally, flows resumed and rose

sharply when the US government responded to the crisis

with huge infusions of cheap liquidity into the system,

aimed at relaxing the liquidity crunch. A substantial

part of the so-called stimulus consisted of periodic

resort to ''quantitative easing'' or the loosening of

monetary controls.

This close link between monetary policy in the developed

countries and capital flows to emerging markets is of

particular significance because, with the turn to fiscal

conservatism, the monetary lever has become the principal

instrument for macroeconomic management. Since that

lever can be moved in either direction (monetary easing

or stringency), net flows can move either into or out

of emerging markets. As a corollary, the consequence

of monetary policy being in ascendance is a high degree

of volatility and lowered persistence of capital inflows

to these countries.

From the point of view of developing countries the implications

are indeed grave. When global conditions are favourable

for an inflow of capital to the developing countries,

these countries experience a capital surge. This creates

problems for the simultaneous management of the exchange

rate and monetary policy in these countries, and leads

to the costly accumulation of excess of foreign exchange

reserves. Costly because the return earned from investing

accumulated reserves is a fraction of that earned by

investors who bring this capital to the developing economy.

Moreover, when global conditions turn unfavourable for

capital flows, capital flows out, reserves are quickly

depleted and there is much uncertainty in currency and

financial markets.

The problem is particularly acute for countries that

are more integrated with US financial markets, since

dependence on the monetary level is far greater in that

country, partly because of the advantages derived from

the dollar being the world's reserve currency. The IMF's

WEO, therefore, predicts: ''economies with greater direct

financial exposure to the United States will experience

greater additional declines in net flows because of

U.S. monetary tightening, compared with economies with

lesser U.S. financial exposure.'' This tallies with

the evidence. Overall, ''event studies demonstrate an

inverted V-shaped pattern of net capital flows to EMEs

around events outside the policymakers' control, underscoring

the fickle nature of capital flows from the perspective

of the recipient economy.''

This increase in externally driven vulnerability explains

the IMF's recent rethink on the use of capital controls

by developing countries. Having strongly dissuaded countries

from opting for such controls in the past, the IMF now

seems to have veered around to the view that they may

not be all bad. However, its endorsement of such measures

has been grudging and partial. In a report prepared

in the run up to this year's spring meetings of the

Fund and the World Bank, the IMF makes a case for what

it terms capital flow management measures, but recommends

them as a last resort and as temporary measures, to

be adopted only when a country has accumulated sufficient

reserves and experienced currency appreciation, despite

having experimented with interest rate policies. This

may be too little, too late. But, fortunately, many

developing countries have gone much further. Only a

few like India, which is also the target of a capital

surge, seem still ideologically disinclined.

*

This article was originally published in The Businessline,

3 May, 2011.

|

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|