One

of the many aspects of growing economic inequality

in India in the period of economic reforms has been

spatial, expressed for example in regional and state-level

differences in per capita income. This feature has

been much less commented upon than other vertical

measures of income distribution, but it is nonetheless

quite marked.

The Central Statistical Organisation (hereafter CSO)

provides information on both gross and net State Domestic

Product. While the CSO emphasises that differences

in methods of data collection imply that the data

are not strictly comparable across states, the information

can nevertheless be used to get some idea of the differences

across space and over time. In what follows, the data

underlying Charts 1 to 5 have been calculated from

estimates of per capita Net State Domestic Product

provided by the RBI based on these CSO estimates.

All the numbers are at constant 2004-05 prices, derived

by splicing various series since 1980-81.

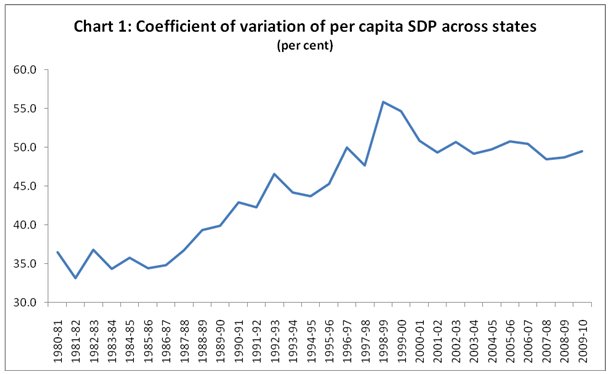

The growing income disparity across states is evident

from Chart 1, which shows the coefficient of variation

of per capita NSDP at 2004-05 prices for 24 states

(some of the Northeastern states had to be excluded

because of insufficient data). It is evident that

the real increase in such inequality was in the 1990s,

which was a period of sharply rising divergence. This

process reached a climax in 1998-99, with a standard

deviation of 56 per cent across the different states.

By contrast, the period of the 1980s showed relatively

lower variation across states, while the 2000s have

been a period of high but stable differences.

Chart

1 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

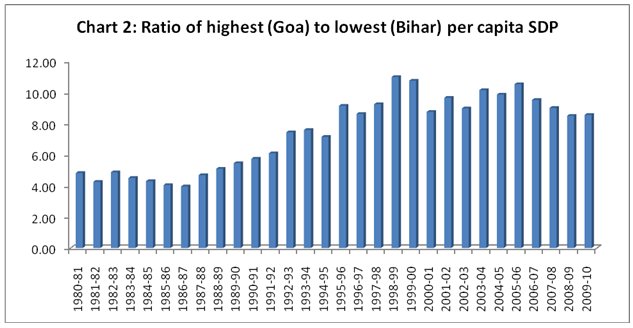

Such

a trend is confirmed by Chart 2, which indicates the

difference between the richest (Goa) and poorest (Bihar)

states. Throughout the 1980s, the per capita NSDP

in Goa was around 4.5 times that of Bihar. In the

1990s, however, this difference increased sharply

and continuously, reaching a peak of nearly 11 times

in 1998-99. In the subsequent and most recent decade,

the ratio fell slightly but stabilised around a high

level, at an average of nearly ten times.

Chart

2 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Clearly, the economic reforms that began in 1991 were

associated with processes that generated rising horizontal

inequality, which peaked around the close of that

decade. In the 2000s, state per capita income divergences

remained high, but did not keep increasing.

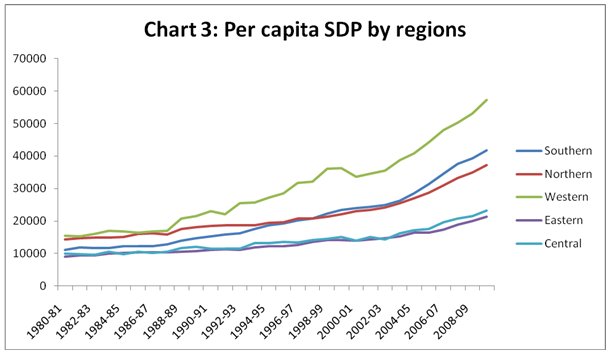

This was then reflected also in broader regional differences

as well. Chart 3 groups the states into five major

regions as follows:

-

Southern - Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra

Pradesh

-

Northern – Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu

and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand

-

Western – Goa, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan

-

Eastern – West Bengal, Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand (the

smaller Northeastern states are excluded)

-

Central – Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh.

It

is true that these regional groupings bring together

some of the richer and poorer states (for example the

Northern region contains both one of the continuously

richer states Haryana and one of the continuously poorer

states Uttar Pradesh). Nevertheless it is evident that

through most of the 1980s regional differences were

very subdued and did not increase much. But from the

end of that decade, and especially from 1991-92, the

per capita SDP of the western and southern regions rose

much faster. The last decade of the 2000s was marked

by an acceleration of per capita income in all the regions,

even though it was still slower in the eastern and central

regions.

Chart

3 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Some of this can be related to the nature of the aggregate

growth process in the country from the 1990s, which

was heavily biased in favour of corporate expansion.

The regions with a greater spread of large capital

in organised activities – such as the western and

southern regions, which include the states of Maharashtra

and Tamil Nadu respectively – therefore showed more

rapid growth in per capita incomes.

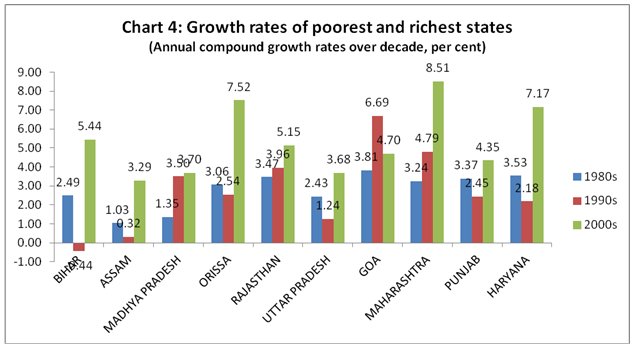

This process can be further unbundled into an examination

of the growth rates of per capita income by decade

for the poorest and richest states, so as to provide

more insights into what exactly was happening in these

three periods. Chart 4 provides data on annual compound

growth rates of per capita NSDP, calculated by taking

three year averages of the beginning and end of each

decade. The six poorest large states are those that

have been referred to as ''BIMAROU'', while the richest

states include the western states of Goa and Maharashtra

and the northern states of Punjab and Haryana.

Several interesting points emerge from this chart.

First, growth rates of per capita income in the 1980s

were broadly similar across the richest and poorest

states, at between 2 and 3 per cent per annum. Although

Assam experienced slightly lower growth and Goa and

Maharashtra slightly higher growth in this decade,

the differences were not large. In the 1990s, Goa

and Maharashtra in particular grew much faster than

the poorer states, accentuating the gap. Indeed, in

this period Bihar and Assam showed stagnation/decline

in per capita incomes, while Uttar Pradesh also had

slow growth. However, growth also slowed down in Punjab

and Haryana.

Chart

4 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

The most recent decade indicates an acceleration in

expansion of per capita incomes across all of these

states. While the fastest growth was experienced in

Maharashtra, surprisingly some of the poorer states

– particularly Orissa followed by Bihar – also had

relatively rapid growth. The base effect meant that

this did not translate into reduction in state-wise

inequalities, but therefore they also did not increase

further.

Obviously, increasing per capita income need not translate

into better performance in terms of poverty reduction

if the growth within the state has been unequally

distributed. However, in fact Orissa does also show

significant reductions in poverty as well, according

to the latest National Sample Survey of 2009-10.

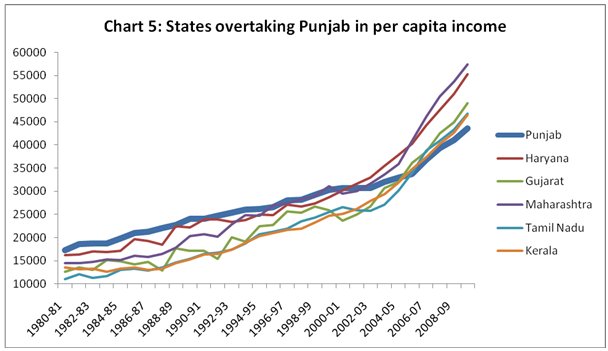

One interesting feature of the past decade in particular

has been that this rapid aggregate growth has generated

a change in the relative ranking of states. (Of course

the caveat that these NSDP figures are not strictly

comparable across states should be borne in mind here.)

In particular, some of the previously middle-income

states have grown rapidly enough in the last decade

to overtake Punjab, which earlier had the second highest

per capita NSDP in the country after Goa.

Chart 5 shows that five states have overtaken Punjab

in terms of per capita income by 2009-10. Both Maharashtra

and Haryana now have significantly higher per capita

NSDP, though that is not really so surprising since

they were both relatively high income states even

in the 1980s and they both overtook Punjab at the

turn of the century.

But there are other surprises, particularly Tamil

Nadu and Kerala. In 1980-81, per capita income in

Punjab was 56 per cent higher than in Tamil Nadu and

27 per cent higher than in Kerala – quite substantial

differences. The advantage of Punjab remained through

most of the period, really until the middle of the

2000s. However, in the latter half of the 2000s, faster

growth in both of these states meant that they now

have higher per capita incomes, with the difference

between 6-8 per cent.

Chart

5 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

This is not really due to income stagnation in Punjab,

since Chart 5 indicates that even in Punjab there

was an acceleration of growth from around 2005-06.

Rather, it was because growth in these other states

was even faster from the early part of the last decade.

What explains this movement, and these differing trends

across the decades? Obviously this is a complex issue

and many factors would have contributed, both at an

all-India level as well as state-specific factors.

Much more research is required to delve into the causes

of these varying trends. However, some broad hypotheses

can be formulated.

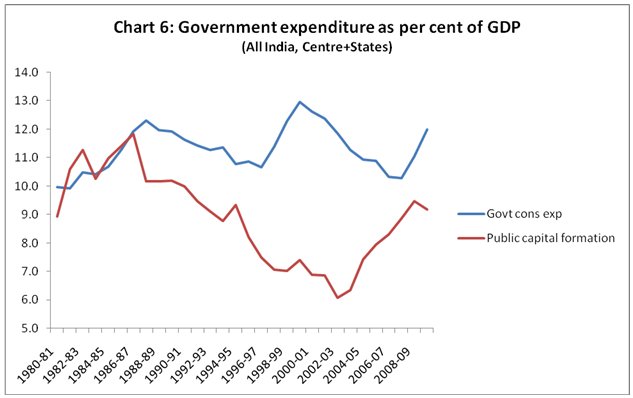

The initial period of economic reform was one in which

the state – at both Central and State levels – significantly

reduced its own spending on both consumption and investment

as shares of GDP. This is confirmed by Chart 6, which

provides aggregate public spending data from the national

accounts. The various liberalisation measures introduced

in the early 1990s generated a much greater role for

private investment, which did actually rise to fill

the gap, but did so in a way that reinforced or aggravated

existing regional inequalities. This can be expected,

since market incentives tend to follow the hysteresis

created by earlier patterns of investment and thereby

lead to enhanced regional (or state-wise) concentration

of economic activity.

Chart

6 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

The latest decade has been rather different, however,

because it has been marked particularly by some revival

of public investment, as Chart 6 illustrates. Public

capital investment (by both Centre and States) fell

continuously as a share of GDP from the peak of nearly

12 per cent in 1986-87 to as low as 6.1 per cent by

2002-03 (just above half of the previous peak rate).

Since then there has been some recovery and increase,

such that by 2009-10, the rate (at just above 9 per

cent) was similar to that achieved in the early 1990s

before the economic reform programme began in earnest.

If this argument is developed, it can then be surmised

that an important means of reducing regional and spatial

income differences is through increasing public investment.

This also leads to a somewhat different understanding

of the nature of the recent aggregate economic success

of the country as a whole: from the generally acclaimed

but somewhat simplistic role ascribed to private investment,

to a more balanced and nuanced appreciation of the

important role of public spending.

*

This article was originally published in the Business

Line, 14 May 2012, and is available at

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/colu

mns/c-p-chandrasekhar/article3418631.ece

|