Themes > Features

06.11.2007

Assessing the World Export Boom

In recent times, the world economy is supposed to have been booming more

than ever before, and especially in relation to the past three decades.

This boom cannot be because of GDP growth, because aggregate world GDP

continues to grow at the same rate of between 2.5 per cent and 3.5 per

cent that has been evident since the 1990s. Indeed, since this is

calculated in US dollar terms, and the dollar has recently been

depreciating somewhat, it is likely that world GDP is not growing faster

than the historical trend even in the most recent period.

So if there is any discussion of boom, it is basically because world trade has been widely perceived to be expanding very rapidly. The recent export growth is seen to be not only much more rapid than the growth of world GDP, but also much higher than the past growth of exports. And this in turn is typically linked to the emergence of some developing economies – notably India and China in Asia, but also others – as major global economic players, who are increasingly exporting not just to the developed world but also to each other.

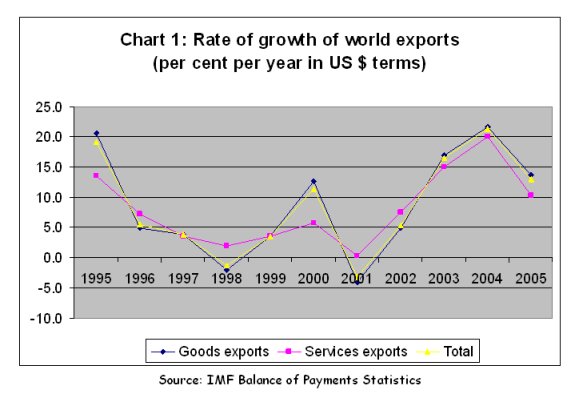

Chart 1 describes the annual expansion of world export values. Clearly, the period since 2002 has shown acceleration of export growth compared to the period just after the mid-1990s. However, it is also evident that export growth was very rapid in the mid-1990s – in fact, it so happens that the three year period 1994-96 showed rates of export growth that were just as high as they were in 2003-05. Interestingly, both merchandise exports and service exports show similar growth patterns, despite the popular perception that services exports have been growing faster.

So if there is any discussion of boom, it is basically because world trade has been widely perceived to be expanding very rapidly. The recent export growth is seen to be not only much more rapid than the growth of world GDP, but also much higher than the past growth of exports. And this in turn is typically linked to the emergence of some developing economies – notably India and China in Asia, but also others – as major global economic players, who are increasingly exporting not just to the developed world but also to each other.

Chart 1 describes the annual expansion of world export values. Clearly, the period since 2002 has shown acceleration of export growth compared to the period just after the mid-1990s. However, it is also evident that export growth was very rapid in the mid-1990s – in fact, it so happens that the three year period 1994-96 showed rates of export growth that were just as high as they were in 2003-05. Interestingly, both merchandise exports and service exports show similar growth patterns, despite the popular perception that services exports have been growing faster.

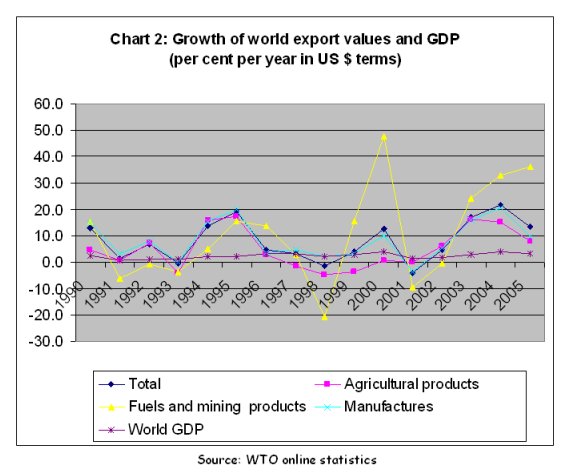

The

recent export growth is also seen as one which benefits a wide range of

developing countries, because it has applied not only to the manufactured

exports of emerging economies, but also to primary commodities – fuels

and minerals as well as agricultural commodities. Chart 2 reiterates first

of all the well-known point that export growth has generally been faster

than world GDP growth, barring the two year 1998 and 2001, when world

export values actually fell.

It also indicates another well-known point: that there has been great volatility of trade in fuels and minerals, essentially reflecting price volatility. While business cycle movements appear to have affected all the main categories of world exports in the same way, the changes in export value have been much sharper for fuels and minerals.

The third point evident from Chart 2 is that in the period 2002-04, all categories of exports grew rapidly. However, in 2005, there were already signs of a slight slowing down of export growth in manufactures, and to a lesser extent services, whereas the growth in value of fuel and mineral exports continued to accelerate.

It also indicates another well-known point: that there has been great volatility of trade in fuels and minerals, essentially reflecting price volatility. While business cycle movements appear to have affected all the main categories of world exports in the same way, the changes in export value have been much sharper for fuels and minerals.

The third point evident from Chart 2 is that in the period 2002-04, all categories of exports grew rapidly. However, in 2005, there were already signs of a slight slowing down of export growth in manufactures, and to a lesser extent services, whereas the growth in value of fuel and mineral exports continued to accelerate.

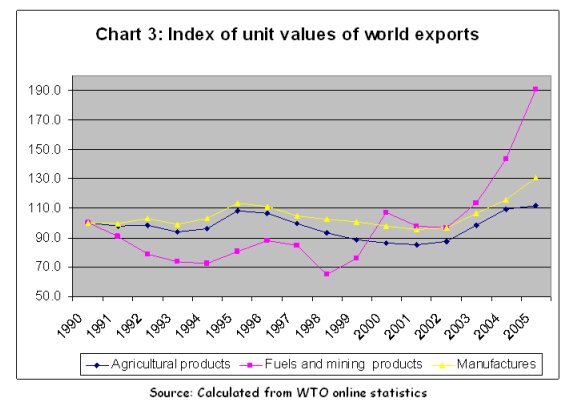

But

how much of this change in the value of world exports can be traced to

price movements rather than real increases? In the case of fuels and minerals,

quite a lot, apparently. Chart 3 shows the movement in unit values of

exports by main category. Some features of this need to be noted. First,

price trends operated a depressing effect on most categories of world

trade from the mid 1990s to 2001.

In the case of agricultural trade, adverse price movements were so marked that the unit value of all agricultural exports fell by more than 21 per cent between 1995 and 2001. The subsequent recovery in agricultural prices from 2002 was still muted – only in 2004 and 2005 have average unit values of exported agricultural products exceeded the levels of the mid-1990s. And of course, in terms of long-run trends, these were still below the levels of the mid-1970s.

The recent explosion in unit values of fuels and mineral exports comes as no surprise, given the surge in oil prices. However, what is interesting to note is how prices of manufactured goods have increased. This comes just after a period of perceptions of excess creation of capacity for many manufactured goods in different parts of the developing world, and fears that this excess capacity creation would drive down prices. Instead we find that manufacturing exports have increased in both volume and value terms.

In 2005, however, an even more interesting movement is apparent for manufactured goods exports: a very sharp increase in unit values (and therefore prices) and a deceleration in volumes, such that aggregate export growth in this category was lower than in the previous year. Although it may be premature to make any assessment based on only this one year, more recent trends in some manufactured goods prices in world trade (including steel, cement and other construction-related material) suggest that there may be some short-run supply constraints affecting prices even as demand for these goods continues to increase globally.

In the case of agricultural trade, adverse price movements were so marked that the unit value of all agricultural exports fell by more than 21 per cent between 1995 and 2001. The subsequent recovery in agricultural prices from 2002 was still muted – only in 2004 and 2005 have average unit values of exported agricultural products exceeded the levels of the mid-1990s. And of course, in terms of long-run trends, these were still below the levels of the mid-1970s.

The recent explosion in unit values of fuels and mineral exports comes as no surprise, given the surge in oil prices. However, what is interesting to note is how prices of manufactured goods have increased. This comes just after a period of perceptions of excess creation of capacity for many manufactured goods in different parts of the developing world, and fears that this excess capacity creation would drive down prices. Instead we find that manufacturing exports have increased in both volume and value terms.

In 2005, however, an even more interesting movement is apparent for manufactured goods exports: a very sharp increase in unit values (and therefore prices) and a deceleration in volumes, such that aggregate export growth in this category was lower than in the previous year. Although it may be premature to make any assessment based on only this one year, more recent trends in some manufactured goods prices in world trade (including steel, cement and other construction-related material) suggest that there may be some short-run supply constraints affecting prices even as demand for these goods continues to increase globally.

But

of course, for this to happen, there must be must be relatively new sources

of demand that counterbalance the adverse effect of the slowing US economy.

The Asian region – led by the rapidly growing economies of China and India

– is widely perceived to be the source of this new demand. Certainly,

as Table 1 indicates, there is evidence of some shifts in the pattern

of international manufactured goods trade across regions. Over the period

2000-05 as a whole, intra-Asian exports manufactured grew at 11 per cent

per annum, the same rate as exports between Europe and Asia, and much

higher than Asian exports to North America.

However, Table 1 also shows that the really big increase in intra-Asian trade occurred in 2004, and that this decelerated quite sharply in 2005. Asian demand for European exports also appears to have showed down significantly in 2005 compared to the previous year. The announcements of Asia becoming a growth pole that can successfully counteract the predicted downturn in the US may be premature, especially given that Asian exports to North America and Europe still remain a basic primary impetus as a source of final demand in that region.

However, Table 1 also shows that the really big increase in intra-Asian trade occurred in 2004, and that this decelerated quite sharply in 2005. Asian demand for European exports also appears to have showed down significantly in 2005 compared to the previous year. The announcements of Asia becoming a growth pole that can successfully counteract the predicted downturn in the US may be premature, especially given that Asian exports to North America and Europe still remain a basic primary impetus as a source of final demand in that region.

Table 1 :Regional Flows in Manufactured Exports in 2005

|

Value. $ bn |

Annual Percentage

Change |

|||

|

2005 |

2000-05 |

2004 |

2005 |

|

Intra - Europe |

2505.6 |

10 |

20 |

5 |

Intra - Asia |

1090.1 |

11 |

25 |

12 |

Intra - North America |

599.2 |

2 |

12 |

8 |

Asia to North America |

562.5 |

7 |

20 |

13 |

Asia to Europe |

447.4 |

11 |

27 |

15 |

Europe

to North America |

331.5 |

7 |

13 |

5 |

Europe to Asia

|

291.8 |

11 |

22 |

6 |

|

Source : WTO World Trade Report, 2006. |

||||

Table 2 provides a disaggregated look at the main categories of exports within manufactured goods. One evident point is that the really significant boom years for world manufactured exports were 2003 and 2004. In 2005, there has been deceleration of manufactured goods exports in the aggregate, and also for every single major category of manufactured goods. While the rates of export growth still remained high in 2005, they were significantly below the growth of the previous two years.

Table 2: Growth Rte of World Manufactured

Goods Exports

|

Percent Change per year in US $ Terms |

||||

|

|

2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|

Total Manufactured Goods |

5.4 | 15.8 | 20.5 | 9.9 |

| Iron & Steel | 9.3 | 26.4 | 47.7 | 17.6 |

| Chemicals | 11.7 | 20.2 | 22.2 | 12.3 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 25.9 | 22.8 | 20.6 | 10.0 |

| Machinery & Transport Equipment | 3.6 | 14.5 | 19.9 | 9.1 |

| Office & Telecom Equipment | 1.2 | 12.6 | 20.1 | 10.7 |

| Electronic Data Processing & Office Equipment | -1.1 | 12.9 | 16.2 | 8.0 |

| Telecommunications Equipment | 1.7 | 13.2 | 26.4 | 19.0 |

| Integrated Circuits & Electronic Components | 3.9 | 11.8 | 18.5 | 4.5 |

| Automotive Products | 10.4 | 16.0 | 17.5 | 6.5 |

| Textiles | 4.1 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 3.9 |

| Clothing | 6.2 | 13.1 | 11.4 | 6.4 |

|

Source: WTO online statistics |

||||

Note

that these rates of growth of export value reflect continuing increases

in prices of some of these goods, especially iron and steel and pharmaceuticals,

so that volume growth would have been much less in 2005. All this suggests

that the recent boom in exports may well be a rather short-lived phenomenon,

rather than a structural break from past trends.

©

MACROSCAN 2007