Themes > Features

04.11..2008

Prospect of an Industrial Recession

Expectations

are that India would experience an industrial slowdown triggered by the

effects of the financial turmoil on the real economy. The most up to date

evidence on the growth of the manufacturing sector is the movement of

the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), which is a lead indicator of

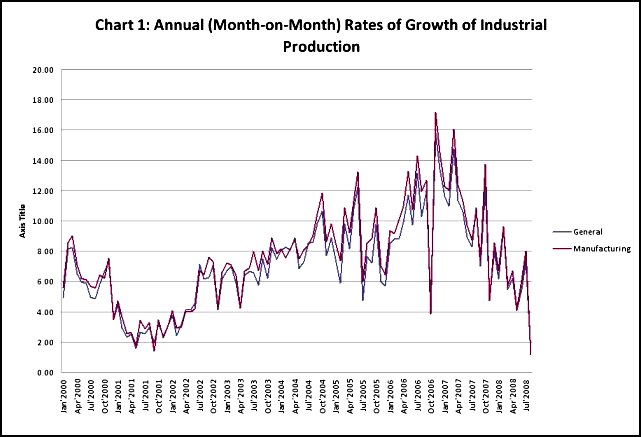

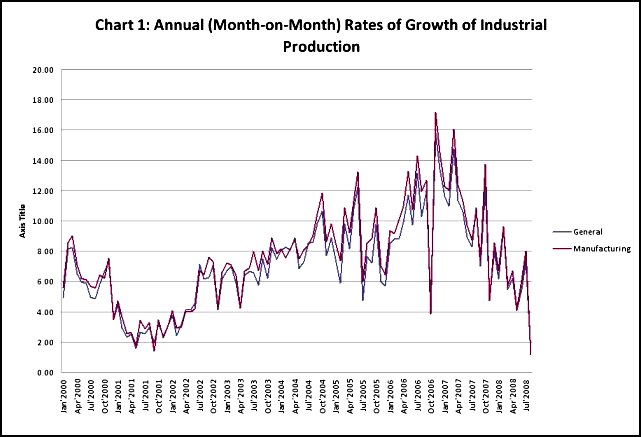

trends in registered manufacturing. Annualised month-on-month rates of

growth of the manufacturing IIP indicate that growth in August 2008 for

industry as a whole and manufacturing in particular were 1.27 per cent

and 1.15 per cent respectively. This compares with 10.86 per cent and

10.75 per cent respectively in the corresponding month of the previous

year.

Despite scepticism about month-on-month annual rates, this decline is disconcerting because it comes after evidence of a medium term slowdown. After touching a trough in September 2001, growth as captured by this index staged a medium term recovery to peak at 17.6 per cent in November 2006 (Chart 1). Since then, despite fluctuations, the trend is one of decline.

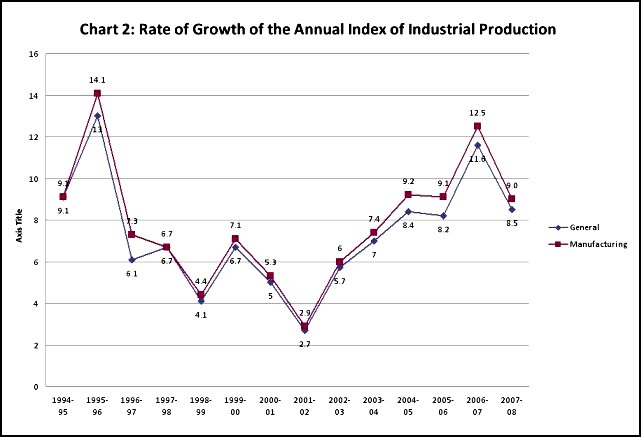

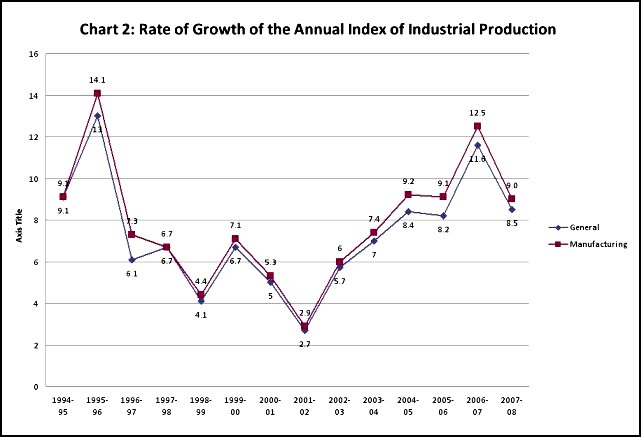

The post-September 2001 evidence on rising or high industrial and manufacturing growth was reassuring, since past experience suggested that high industrial growth has not been the rule under liberalization. Taking a long view, we find that industrial growth as captured by the IIP, which averaged 9 per cent in the second half of the 1980s, slumped immediately after the balance of payments crisis of 1991 (Chart 2). However, a recovery followed, with manufacturing growth rising to a peak of 14.1 per cent over the three-year period 1993-94 to 1995-96. This led many to argue that liberalization had begun to deliver in terms of industrial growth. But the boom proved short-lived, and industry entered a relatively long period of much slower growth, with fears of an industrial recession being expressed by 2001-02. Since then the industrial sector has once again recovered, with rates of growth touching the high level s of the mid-1990s by 2004-05. Even though the peak of 1995-96 has not been equalled, growth was creditable and sustained over the five years ending 2007-08.

An additional cause for comfort offered by the 2002-03 to 2007-08 experience was that there appeared to be significant differences between the mini-boom of the mid-1990s and what occurred recently. The 1993-1995 “mini-boom” was the result of a combination of several once-for-all influences. Principal among these was the release after liberalization of the pent-up demand for a host of import-intensive manufactures, which (because of liberalization) could be serviced through domestic assembly or production using imported inputs and components. Once that demand had been satisfied, further growth had to be based on an expansion of the domestic market or a surge in exports. Since neither of these conditions was realized, industry entered a phase of slow growth.

What was surprising, in fact, was that the deceleration in growth after 1997 growth was not even sharper. This was because there were features of economic liberalization and fiscal reform that were bound to adversely affect manufacturing growth. To start with, import liberalization results in some displacement of existing domestic production directly by imports and indirectly by new products assembled domestically from imported inputs. Second, the reduction in customs duties resorted to as part of the import liberalization package and the direct and indirect tax concessions that were provided to the private sector to stimulate investment, led to a decline in the tax-GDP ratio at the Centre by between around 1.5 percentage points of GDP over the 1990s. This implied that so long as deficit-spending by the government did not increase, the demand stimulus associated with government expenditure would be lower than would have otherwise been the case. Third, after 1993-94 the government also chose to significantly restrict the fiscal deficit as part of fiscal reform. Success on this front was delayed, but began to be achieved by the late 1990s, making the stimulus provided to industrial growth by state expenditure substantially smaller than was the case in the 1980s. These were among the factors that slowed industrial growth after the mid-1990s.

If the stimulus to industrial growth was dampened after the late 1990s, what explains the post-2002 recovery in industrial growth? That recovery was in large measure due to the increases in private consumption and housing investment resulting from two important developments. One is the much faster increases in income in the top deciles of the population. It is known that these do not get effectively reflected in consumption expenditure surveys and inequality calculations based on them, because these surveys inadequately cover the upper income groups. Yet a comparison of the mean real per capita consumption expenditure by decile groups (Table 1) indicates that the rate of growth of mean consumption expenditure in the highest decile in both rural and urban areas rose much faster than in the other decile groups. Moreover, not only did aggregate mean consumption expenditure in the urban areas increase at a rate (22 per cent) much faster than in rural areas (5.5 per cent), but in the urban areas the rates of growth of such expenditure in the top five deciles, (which ranged between 19 and 33 per cent) was much higher than in lower five deciles (between 10.4 and 16 per cent). (Inequality in consumption expenditure as measure by the gini coefficient rose from 0.286 to 0.305 in rural areas and from 0.344 to 0.367 in urban areas during this period.) This meant that there would have been some diffusion of luxury consumption to those below the topmost deciles in the urban areas.

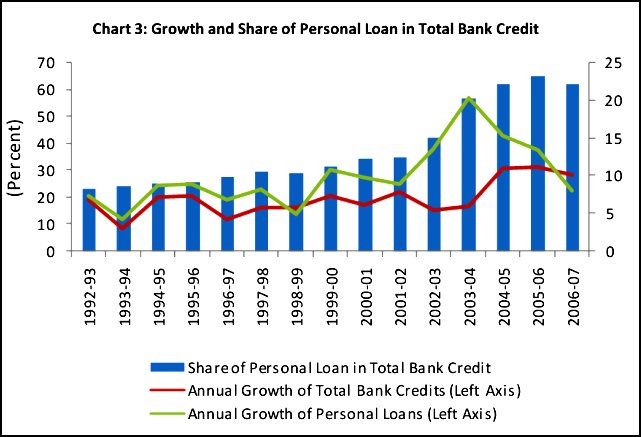

The second development is the sharp increase in credit financed housing investment and consumption, facilitated by financial liberalization, which played an extremely important role in keeping industrial demand at high levels. Credit served as a stimulus to industrial demand in three ways. First, it financed a boom in investment in housing and real estate and spurred the growth in demand for construction materials. Second, it financed purchases of automobiles and triggered an automobile boom. Finally, it contributed to the expansion in demand for consumer durables.

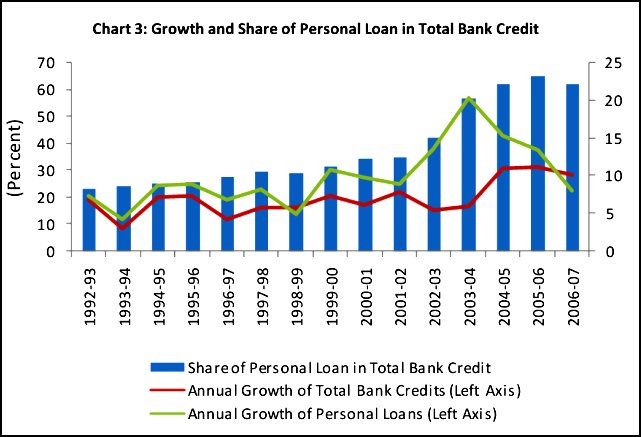

The point to note is that compared to the mid-1990s the growth of credit in recent years has been explosive, facilitated in part by the liquidity injected into the system by the large inflows of foreign financial capital in the form of equity and debt. In the wake of this increase in liquidity, expansion in credit provision has been accompanied by an increase in the exposure of the banking sector to the retail loan segment. The share of personal loans in total bank credit has risen sharply since the beginning of liberalisation, almost trebling from 8.3 per cent in 1992-93 to 12.2 per cent during 2000-2001 to 242.3 per cent in 2006-07 (Chart 3). Much of this has been concentrated in housing finance, with housing loans accounting for just above 51 per cent of personal loans in 2007. But purchasers of automobiles and consumer durables have also received a fair share of credit.

Another element of change in the factors contributing to industrial growth during the current boom as opposed to that in the mid-1990s is the stimulus provided by exports. In the early and mid-1990s high growth was accompanied by high imports, with exports growing, if at all, in areas where India was traditionally strong. In recent years, the share of India’s traditional manufactured exports such as textiles, gems and jewellery and leather in the total exports of manufactures has declined, while that of chemicals and engineering goods has gone up significantly. This would have stimulated growth. While exports are by no means the principal drivers of manufacturing production, they play a part in sectors like automobile parts and chemicals and pharmaceuticals where Indian firms are increasingly successful in global markets.

The Pattern of Demand

The nature of the stimuli underlying recent industrial growth does have implications for the pattern of demand. An important implication of debt-financed manufacturing demand is that it is inevitably concentrated in the first instance in a narrow range of commodities that are the targets of personal finance. Commodities whose demand is expanded with credit finance vary from construction materials to automobiles and consumer durables.

A disaggregated picture of the pattern of organised industrial sector growth can be drawn based on movements in net value added at the three-digit level in industries covered by the Annual Survey of industries (ASI), a comparable series for which for the period 1973-74 to 2003-04 has been prepared by the EPW Research Foundation.

To adjust the series for changes in prices, the three-digit level industries have been matched with appropriate combinations of commodities covered in the series on Wholesale Price Indices with base year 1993-94 published by the Office of the Economic Adviser in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. Where a perfect match for a particular three-digit industry group was not available, price indices for three-digit groups have been arrived at by weighting the index of each commodity within the group with the relative weight attached to it in the WPI. Using these indices, figures on value added at the three-digit level have been deflated to compute inflation-adjusted values for each year.

One feature which emerges from the resulting series on net value added is the wide variation in growth at the three digit level with high growth being concentrated in relatively few industries. To calculate the contribution of the fastest growing industries to the overall rate of growth of these 52 three-digit level industries, we multiply the compound rate of growth in any particular three-digit industry (implicit in the real net value added in 1993-94 and 2003-04) with the share of value added in this industry relative to all 52 industries in the base year, and divide the resulting figure by the sum of the weighted growth rates of net value added all 52 industries. The top 3 growth contributing industries during the period 1993-94 to 2003-04 accounted for 38 per cent of the growth in all industries, with the figure for the top 5 rising to close to 55 per cent, the top 10 to almost 75 per cent and for the top 15 to almost 90 per cent. There were 39 industries that recorded a positive rate of growth for this period. If we restrict our analysis to those industries that registered a positive rate of growth over the period, the picture of concentration still persists (Table 2). The top 3 growth contributors over the period 1993-94 to 2003-04 accounted for more than a third of growth in all industries with a positive rate of growth, with the figure for the top 5 rising to close to 50 per cent, the top 10 to more than two-thirds and for the top 15 to almost 80 per cent. This pattern of growth distribution characterised the two sub-periods into which the whole period has been divided.

An examination of the industries that fall in the category of highest growth contributing industries shows that these consist largely of the metal and chemical industries gaining from the credit financed construction and consumption boom, including areas like automobiles, television receivers and computing equipment. The leading sectors also include many chemical industries that feed luxury consumption, like refined petroleum products. Finally, the leaders include those industries that may have benefited from new export opportunities such as iron and steel and chemicals.

This concentration of growth in industries that have benefited from the stimuli offered by credit-financed investment and consumption and exports has obvious implications for the fall-out of recent developments in financial and currency markets. One development is that the FII exodus has resulted in a sharp depreciation of the rupee, despite RBI intervention to an extent where foreign exchange reserves have fallen by more the $50 billion. In normal circumstances this would have stimulated exports and industrial growth. The problem, however, is that the currencies of India’s competitors are depreciating as well. So export benefits are limited. On the other hand, global markets are showing signs of slowdown, affecting export demand adversely. This would slow growth.

The second fall-out of significance is that the financial turmoil is slowing credit growth, including retail credit growth where defaults are reportedly rising and are likely to rise further if the economy slows down. The Finance Ministry and the RBI thought this problem could be dealt with by pumping liquidity and easing interest rates. The experience here and elsewhere suggest that this would not work. In the circumstances, the recent sharp fall in the month-on-month growth rate of the IIP may not be too far off the mark. Unless the government recognises that a proactive, deficit-financed fiscal strategy is not bad but good policy.

Despite scepticism about month-on-month annual rates, this decline is disconcerting because it comes after evidence of a medium term slowdown. After touching a trough in September 2001, growth as captured by this index staged a medium term recovery to peak at 17.6 per cent in November 2006 (Chart 1). Since then, despite fluctuations, the trend is one of decline.

The post-September 2001 evidence on rising or high industrial and manufacturing growth was reassuring, since past experience suggested that high industrial growth has not been the rule under liberalization. Taking a long view, we find that industrial growth as captured by the IIP, which averaged 9 per cent in the second half of the 1980s, slumped immediately after the balance of payments crisis of 1991 (Chart 2). However, a recovery followed, with manufacturing growth rising to a peak of 14.1 per cent over the three-year period 1993-94 to 1995-96. This led many to argue that liberalization had begun to deliver in terms of industrial growth. But the boom proved short-lived, and industry entered a relatively long period of much slower growth, with fears of an industrial recession being expressed by 2001-02. Since then the industrial sector has once again recovered, with rates of growth touching the high level s of the mid-1990s by 2004-05. Even though the peak of 1995-96 has not been equalled, growth was creditable and sustained over the five years ending 2007-08.

An additional cause for comfort offered by the 2002-03 to 2007-08 experience was that there appeared to be significant differences between the mini-boom of the mid-1990s and what occurred recently. The 1993-1995 “mini-boom” was the result of a combination of several once-for-all influences. Principal among these was the release after liberalization of the pent-up demand for a host of import-intensive manufactures, which (because of liberalization) could be serviced through domestic assembly or production using imported inputs and components. Once that demand had been satisfied, further growth had to be based on an expansion of the domestic market or a surge in exports. Since neither of these conditions was realized, industry entered a phase of slow growth.

What was surprising, in fact, was that the deceleration in growth after 1997 growth was not even sharper. This was because there were features of economic liberalization and fiscal reform that were bound to adversely affect manufacturing growth. To start with, import liberalization results in some displacement of existing domestic production directly by imports and indirectly by new products assembled domestically from imported inputs. Second, the reduction in customs duties resorted to as part of the import liberalization package and the direct and indirect tax concessions that were provided to the private sector to stimulate investment, led to a decline in the tax-GDP ratio at the Centre by between around 1.5 percentage points of GDP over the 1990s. This implied that so long as deficit-spending by the government did not increase, the demand stimulus associated with government expenditure would be lower than would have otherwise been the case. Third, after 1993-94 the government also chose to significantly restrict the fiscal deficit as part of fiscal reform. Success on this front was delayed, but began to be achieved by the late 1990s, making the stimulus provided to industrial growth by state expenditure substantially smaller than was the case in the 1980s. These were among the factors that slowed industrial growth after the mid-1990s.

If the stimulus to industrial growth was dampened after the late 1990s, what explains the post-2002 recovery in industrial growth? That recovery was in large measure due to the increases in private consumption and housing investment resulting from two important developments. One is the much faster increases in income in the top deciles of the population. It is known that these do not get effectively reflected in consumption expenditure surveys and inequality calculations based on them, because these surveys inadequately cover the upper income groups. Yet a comparison of the mean real per capita consumption expenditure by decile groups (Table 1) indicates that the rate of growth of mean consumption expenditure in the highest decile in both rural and urban areas rose much faster than in the other decile groups. Moreover, not only did aggregate mean consumption expenditure in the urban areas increase at a rate (22 per cent) much faster than in rural areas (5.5 per cent), but in the urban areas the rates of growth of such expenditure in the top five deciles, (which ranged between 19 and 33 per cent) was much higher than in lower five deciles (between 10.4 and 16 per cent). (Inequality in consumption expenditure as measure by the gini coefficient rose from 0.286 to 0.305 in rural areas and from 0.344 to 0.367 in urban areas during this period.) This meant that there would have been some diffusion of luxury consumption to those below the topmost deciles in the urban areas.

The second development is the sharp increase in credit financed housing investment and consumption, facilitated by financial liberalization, which played an extremely important role in keeping industrial demand at high levels. Credit served as a stimulus to industrial demand in three ways. First, it financed a boom in investment in housing and real estate and spurred the growth in demand for construction materials. Second, it financed purchases of automobiles and triggered an automobile boom. Finally, it contributed to the expansion in demand for consumer durables.

Table

1:

Decile-wise Mean Consumption Expenditure at 1993-94 Prices,

1999-2000 and 2004-05 |

|||

Consumption

Deciles |

Mean

Consumption |

Growth

(%) |

|

| RURAL | 1993-94 | 2004-05 | |

| 1 | 116.25 | 121.05 | 4.13 |

| 2 | 154.03 | 157.95 | 2.54 |

| 3 | 178.18 | 181.74 | 2.00 |

| 4 | 200.75 | 205.02 | 2.12 |

| 5 | 224.27 | 229.08 | 2.14 |

| 6 | 250.84 | 256.37 | 2.21 |

| 7 | 282.38 | 289.11 | 2.38 |

| 8 | 324.59 | 334.13 | 2.94 |

| 9 | 395.59 | 409.99 | 3.64 |

| 10 | 687.19 | 783.92 | 14.08 |

| TOTAL |

281.40 |

296.84 |

5.48 |

| ananan | |||

| URBAN | 1993-94 | 2004-05 | |

| 1 | 154.46 | 171.71 | 11.17 |

| 2 | 212.38 | 234.38 | 10.36 |

| 3 | 252.15 | 282.97 | 12.23 |

| 4 | 291.82 | 332.00 | 13.77 |

| 5 | 334.90 | 388.37 | 15.97 |

| 6 | 383.90 | 455.62 | 18.68 |

| 7 | 448.70 | 538.74 | 20.07 |

| 8 | 541.47 | 651.49 | 20.32 |

| 9 | 691.72 | 845.83 | 22.28 |

| 10 | 1268.80 | 1688.94 | 33.11 |

| TOTAL |

458.04 |

559.01 |

22.04 |

|

Source: Computations as part of ongoing research by Himanshu based on National Sample Survey Organisation, Department of Statistics, Government of India 1997 and National Sample Survey Organisation, Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, Government of India 2006. |

|||

The point to note is that compared to the mid-1990s the growth of credit in recent years has been explosive, facilitated in part by the liquidity injected into the system by the large inflows of foreign financial capital in the form of equity and debt. In the wake of this increase in liquidity, expansion in credit provision has been accompanied by an increase in the exposure of the banking sector to the retail loan segment. The share of personal loans in total bank credit has risen sharply since the beginning of liberalisation, almost trebling from 8.3 per cent in 1992-93 to 12.2 per cent during 2000-2001 to 242.3 per cent in 2006-07 (Chart 3). Much of this has been concentrated in housing finance, with housing loans accounting for just above 51 per cent of personal loans in 2007. But purchasers of automobiles and consumer durables have also received a fair share of credit.

Another element of change in the factors contributing to industrial growth during the current boom as opposed to that in the mid-1990s is the stimulus provided by exports. In the early and mid-1990s high growth was accompanied by high imports, with exports growing, if at all, in areas where India was traditionally strong. In recent years, the share of India’s traditional manufactured exports such as textiles, gems and jewellery and leather in the total exports of manufactures has declined, while that of chemicals and engineering goods has gone up significantly. This would have stimulated growth. While exports are by no means the principal drivers of manufacturing production, they play a part in sectors like automobile parts and chemicals and pharmaceuticals where Indian firms are increasingly successful in global markets.

The Pattern of Demand

The nature of the stimuli underlying recent industrial growth does have implications for the pattern of demand. An important implication of debt-financed manufacturing demand is that it is inevitably concentrated in the first instance in a narrow range of commodities that are the targets of personal finance. Commodities whose demand is expanded with credit finance vary from construction materials to automobiles and consumer durables.

A disaggregated picture of the pattern of organised industrial sector growth can be drawn based on movements in net value added at the three-digit level in industries covered by the Annual Survey of industries (ASI), a comparable series for which for the period 1973-74 to 2003-04 has been prepared by the EPW Research Foundation.

To adjust the series for changes in prices, the three-digit level industries have been matched with appropriate combinations of commodities covered in the series on Wholesale Price Indices with base year 1993-94 published by the Office of the Economic Adviser in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. Where a perfect match for a particular three-digit industry group was not available, price indices for three-digit groups have been arrived at by weighting the index of each commodity within the group with the relative weight attached to it in the WPI. Using these indices, figures on value added at the three-digit level have been deflated to compute inflation-adjusted values for each year.

One feature which emerges from the resulting series on net value added is the wide variation in growth at the three digit level with high growth being concentrated in relatively few industries. To calculate the contribution of the fastest growing industries to the overall rate of growth of these 52 three-digit level industries, we multiply the compound rate of growth in any particular three-digit industry (implicit in the real net value added in 1993-94 and 2003-04) with the share of value added in this industry relative to all 52 industries in the base year, and divide the resulting figure by the sum of the weighted growth rates of net value added all 52 industries. The top 3 growth contributing industries during the period 1993-94 to 2003-04 accounted for 38 per cent of the growth in all industries, with the figure for the top 5 rising to close to 55 per cent, the top 10 to almost 75 per cent and for the top 15 to almost 90 per cent. There were 39 industries that recorded a positive rate of growth for this period. If we restrict our analysis to those industries that registered a positive rate of growth over the period, the picture of concentration still persists (Table 2). The top 3 growth contributors over the period 1993-94 to 2003-04 accounted for more than a third of growth in all industries with a positive rate of growth, with the figure for the top 5 rising to close to 50 per cent, the top 10 to more than two-thirds and for the top 15 to almost 80 per cent. This pattern of growth distribution characterised the two sub-periods into which the whole period has been divided.

An examination of the industries that fall in the category of highest growth contributing industries shows that these consist largely of the metal and chemical industries gaining from the credit financed construction and consumption boom, including areas like automobiles, television receivers and computing equipment. The leading sectors also include many chemical industries that feed luxury consumption, like refined petroleum products. Finally, the leaders include those industries that may have benefited from new export opportunities such as iron and steel and chemicals.

Table 2:Contribution

of Fastest Growing Industries to the Aggregate Rate of Growth of ASI Value Added |

|||

|

Contr.

to VA Gr 1993-94-2003-04 |

Contr. to VA Gr 1993-94-1998-99 | Contr. to VA Gr 1998-99-2003-04 | |

| Top 3 | 34.21 | 38.97 | 37.36 |

| Top 5 | 49.00 | 47.66 | 52.50 |

| Top 10 | 67.19 | 63.45 | 75.43 |

| Top 15 | 79.12 | 74.40 | 85.60 |

This concentration of growth in industries that have benefited from the stimuli offered by credit-financed investment and consumption and exports has obvious implications for the fall-out of recent developments in financial and currency markets. One development is that the FII exodus has resulted in a sharp depreciation of the rupee, despite RBI intervention to an extent where foreign exchange reserves have fallen by more the $50 billion. In normal circumstances this would have stimulated exports and industrial growth. The problem, however, is that the currencies of India’s competitors are depreciating as well. So export benefits are limited. On the other hand, global markets are showing signs of slowdown, affecting export demand adversely. This would slow growth.

The second fall-out of significance is that the financial turmoil is slowing credit growth, including retail credit growth where defaults are reportedly rising and are likely to rise further if the economy slows down. The Finance Ministry and the RBI thought this problem could be dealt with by pumping liquidity and easing interest rates. The experience here and elsewhere suggest that this would not work. In the circumstances, the recent sharp fall in the month-on-month growth rate of the IIP may not be too far off the mark. Unless the government recognises that a proactive, deficit-financed fiscal strategy is not bad but good policy.

©

MACROSCAN 2008