Themes > Features

18.11..2008

The Industrial Recession: New or Ongoing?

The

industrial slowdown is now accepted as fact by most policy makers and

observers of the Indian economy. Yet officials and commentators seem to

blame it on external factors: most obviously, the global financial crisis

originating in the US economy, the consequent economic slowdown and now

recession in the US, the European Union and other developed country markets,

and the associated impact upon exports.

It is certainly true that the bad news from abroad – which shows no signs of easing up – has impacted upon domestic stock markets, investor expectations, and the exporting industries in particular. But it is also unfortunately the case that our own economy has been showing several causes for concern even before that external bad news started pouring in. There was the accelerating inflation, which particularly hit food and other items of essential consumption, and recently exacerbated by the increase in petrol prices. In addition there have been signs of decelerating growth, especially in industrial activity, and these cannot be ascribed only to reduced export orders, but are more likely to have domestic causes.

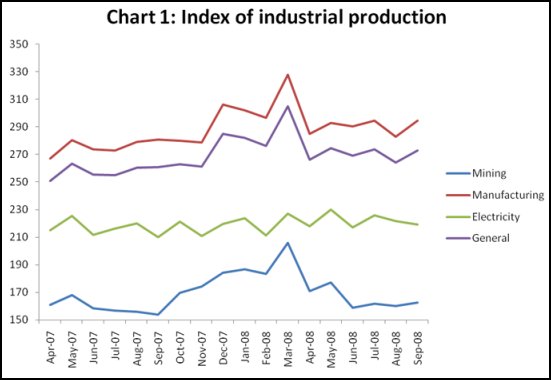

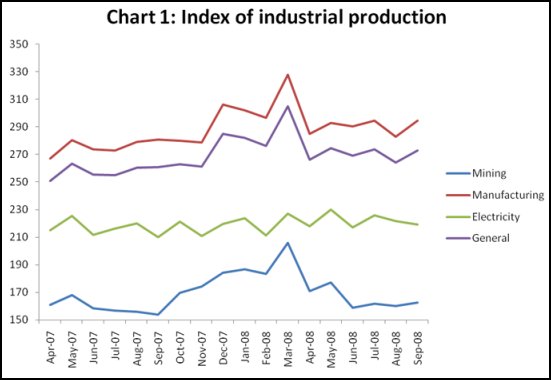

Consider the index of industrial production, presented in Chart 1 (with base year 1993-94). The general index peaked in March this year, fell quite sharply thereafter and subsequently has been more or less flat at the lower level. This pattern essentially reflects the behaviour of the manufacturing index, which accounts for around 80 per cent of the weight of the general index. Such a pattern tends to be obscured by the standard way of presenting the industrial growth data, in terms of year-on-year monthly rates.

What is especially disconcerting is the evidence on electricity production, which shows hardly any increase at all but simply fluctuations around a flat trend for the past 18 months. Since electricity still remains substantially undersupplied, and its shortage can create supply bottlenecks for other production, this stagnation is worth noting.

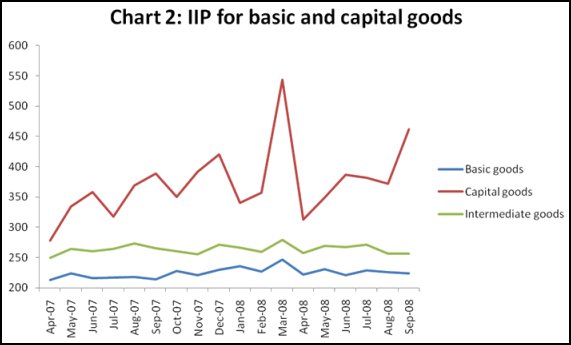

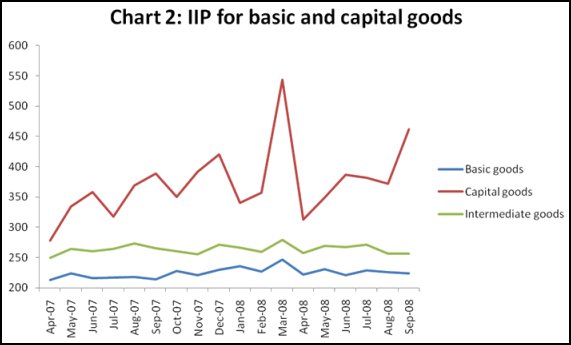

The use-based classification industrial production suggests that the slowdown in growth is spread across several important sectors. Chart 2 provides the evidence on recent trends in production in the basic, capital goods and intermediate industries. Once again, both basic goods and intermediate goods, which have strong backward and forward linkages with other industrial activity, have been stagnant and hardly increased at all over the past one and half years. The production of capital goods shows much greater volatility, with a sharp increase in March 2008 but decline thereafter from that peak.

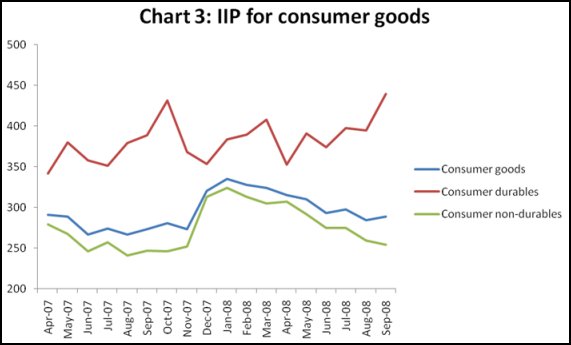

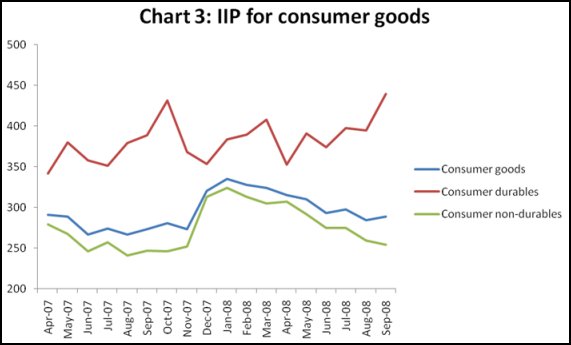

Consumer goods are the most likely - and the first - to be directly affected by slowing demand in domestic and export markets. Chart 3 show that this too is not a recent problem, but one which has been clearly evident in the economy at least since the beginning of the current calendar year. The production of consumer non-durable goods, which account for the bulk of consumer goods (with more than 80 per cent weight) peaked in January 2008 and have fallen continuously since then. Consumer durables, onthe other hand, had benefited from a credit-financed boom that had elements of unsustainability that are eerily similar to the US credit-driven consumption boom. The significant expansion of retail credit, especially credit card debt and hire purchase schemes, had generated demand for consumer durables and automobiles, but such credit-driven expansion became increasingly problematic as interest rates increased and lenders became more concerned with the viability of this rapidly growing consumer debt.

It is certainly true that the bad news from abroad – which shows no signs of easing up – has impacted upon domestic stock markets, investor expectations, and the exporting industries in particular. But it is also unfortunately the case that our own economy has been showing several causes for concern even before that external bad news started pouring in. There was the accelerating inflation, which particularly hit food and other items of essential consumption, and recently exacerbated by the increase in petrol prices. In addition there have been signs of decelerating growth, especially in industrial activity, and these cannot be ascribed only to reduced export orders, but are more likely to have domestic causes.

Consider the index of industrial production, presented in Chart 1 (with base year 1993-94). The general index peaked in March this year, fell quite sharply thereafter and subsequently has been more or less flat at the lower level. This pattern essentially reflects the behaviour of the manufacturing index, which accounts for around 80 per cent of the weight of the general index. Such a pattern tends to be obscured by the standard way of presenting the industrial growth data, in terms of year-on-year monthly rates.

What is especially disconcerting is the evidence on electricity production, which shows hardly any increase at all but simply fluctuations around a flat trend for the past 18 months. Since electricity still remains substantially undersupplied, and its shortage can create supply bottlenecks for other production, this stagnation is worth noting.

The use-based classification industrial production suggests that the slowdown in growth is spread across several important sectors. Chart 2 provides the evidence on recent trends in production in the basic, capital goods and intermediate industries. Once again, both basic goods and intermediate goods, which have strong backward and forward linkages with other industrial activity, have been stagnant and hardly increased at all over the past one and half years. The production of capital goods shows much greater volatility, with a sharp increase in March 2008 but decline thereafter from that peak.

Consumer goods are the most likely - and the first - to be directly affected by slowing demand in domestic and export markets. Chart 3 show that this too is not a recent problem, but one which has been clearly evident in the economy at least since the beginning of the current calendar year. The production of consumer non-durable goods, which account for the bulk of consumer goods (with more than 80 per cent weight) peaked in January 2008 and have fallen continuously since then. Consumer durables, onthe other hand, had benefited from a credit-financed boom that had elements of unsustainability that are eerily similar to the US credit-driven consumption boom. The significant expansion of retail credit, especially credit card debt and hire purchase schemes, had generated demand for consumer durables and automobiles, but such credit-driven expansion became increasingly problematic as interest rates increased and lenders became more concerned with the viability of this rapidly growing consumer debt.

Table 1: Year-On-Year

Growth of IIP for Particular Sectors (per cent) |

||

| September 2008 |

Apr-Sep 2008 |

|

| Food Products | 5.2 | -1.4 |

| Beverages, Tobacco and Related Products | 11.7 | 23.3 |

| Cotton Textiles | -9.3 | -0.5 |

| Wool, Silk and man-made fibre textiles | 1.4 | -0.2 |

| Jute and other vegetable fibre Textiles (except cotton) | -0.4 | -5.5 |

| Textile Products (including Wearing Apparel) | -1.9 | 3.8 |

| Wood and Wood Products; Furniture and Fixtures | -9.7 | -10.4 |

| Paper & Paper Products and Printing, Publishing & Allied Industries | 8.3 | 3 |

| Leather and Leather & Fur Products | -8.6 | -0.3 |

| Basic Chemicals & Chemical Products (except products of Petroleum & Coal) | -3.6 | 6.1 |

| Rubber, Plastic, Petroleum and Coal Products | -3.4 | -4.2 |

| Non-Metallic Mineral Products | -0.6 | 0.6 |

| Basic Metal and Alloy Industries | 5.6 | 6.2 |

| Metal Products and Parts, except Machinery and Equipment | 12.8 | 1.3 |

| Machinery and Equipment other than Transport equipment | 16.1 | 9.8 |

| Transport Equipment and Parts | 16.8 | 12.8 |

| Other Manufacturing Industries | 10.5 | -1.1 |

Table 1 show that this deceleration was widely spread across different manufacturing sectors. Indeed, only the chemicals, machinery and transport equipment sectors appear to still be growing, albeit at slower rates.

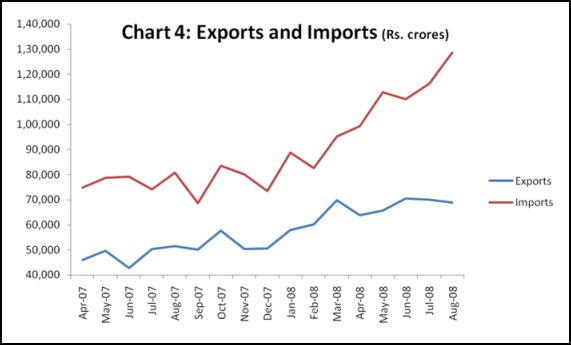

What explains this trend of deceleration even before the outbreak of global financial crisis? One partial explanation can be found in Chart 4, which shows the movement of imports and exports over the same period. It is evident that exports have been growing throughout this period, and so a fall in aggregate export demand cannot yet be blamed for the domestic inudstrial deceleration, although it may indeed have an adverse impact soon. But the explosion in imports is also worth noting, and that suggests that import competition could have affected domestic production of many manufactured goods.

The rapidly growing import bill is only partly a result of the high oil prices that prevailed over most of 2007 and the early part of 2008. Non-oil imports also increased, aided not only by more liberalised trade but also by the appreciation of the rupee in 2007.

Table 2 shows that non-oil imports for the period April-May 2008 compared to the same period in 2007, increased by nearly a quarter. Within that, certain sectors showed very high rates of increase in import values, much more than the growth of domestic production, suggesting some amount of imports penetration in a wide range of manufacturing sectors.

Table 2: Increase in Import Values (in Rs. crore) Y ear-On-Year for April-May 2008 (per cent) |

|

Total

Imports |

38.51 |

POL

imports |

73.61 |

Non-oil

imports |

23.51 |

Textile

products, incl garments |

19.28 |

Chemical

products |

56.53 |

Med

& pharma products |

37.77 |

Artificial

resins & plastics |

47.85 |

Metal

goods |

89.44 |

Machine

tools |

83.41 |

Non-elec

machinery |

47.54 |

Elec

machinery |

58.02 |

Electronic

machinery |

19.65 |

Transport

equipment |

25.62 |

Professional

equipment |

57.05 |

Other

miscellaneous imports |

28.95 |

| Source: DGCI&S | |

This in turn suggests that the deceleration of industry may have resulted from the inability of the government to ensure the macro management of the economy in a complex global situation. The rush of foreign capital into India was acutally sought by the government, whether in the form of (subsequently fickle) portfolio investments or by encouraging Indian corporates take on more external commercial loans. This inflow led to upward pressure on the rupee, and this combined with trade liberalisation to encourage more import penetration. Some of this must definitely have damaged activity and employment among Indian producers, especially the small scale producers who still account for around one-third of manufacturing GDP and much more than two-thirds of manufacturing employment.

Then, the global rise in food and fuel prices was allowed to impact upon prices in India. In response to this, instead of managing these specific items, the government raised interest rates as an anti-inflationary measure. This had the effect of further damaging the prospects for industrial activity. All this happened before the subsequent outflows of captial led to a rapidly depreciating rupee – but by then the damage had been done.

It is pointless to blame external forces, because none of these processes was necessary within India. There was no need to encourage and then suffer the effects of mobile capital flows that brought in resources that were not even going to be used. Instead, capital inflows could simply have been controlled to prevent upward pressure on the exchange rate. Inflation could have been managed by first recognising the essentially speculative and therefore temporary nature of the global fuel and food price rises, and then addressing the specific management of these sectors within the economy.

Unfortunately this previous mismanagement has worse consequences than simply the evident industrial deceleration. It has also weakened the economy even before it faces the full impact of the global recession and the financial turmoil.

©

MACROSCAN 2008