Themes > Features

08.10..2008

Employment and the Pattern of Growth

Estimates

made by the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector

(NCEUS) provide a much clearer picture of employment in the organized

industrial sector than available hitherto. They make the much needed

distinction between “employment in the organized sector” (defined to

include all enterprises employing ten or more workers with power or

20 or more workers without power and therefore seen as subject to the

Factories Act) and “organized employment”, or employment that has associated

with it a minimum of employment, work and social security. If organized

employment is taken to consist of all employment in units that fall

under the formal sector definition, then such employment is estimated

to have risen from 54.1 million to 62.6 million between 1999-2000 and

2004-05. However, if the definition is restricted to “organized workers”

in the organized sector, then “formal” employment in the organized sector

had fallen marginally from 33.7 million in 1999-00 to 33.4 million in

2004-05. This compares with total employment of 361.7 million and 422.6

million respectively on these two dates. With manufacturing employment

having remained near-stagnant at 12.1 and 12.9 million respectively

during these two years, we can safely conclude that the manufacturing

sector’s contribution to organized employment is not just small relative

to the total, but must have stagnated or declined.

It is indeed true that this was expected to some extent given the fact that more than 60 per cent of the increment in GDP in the years after 1991 have come from the services sector, and the manufacturing sector’s share has declined. However, there have been periods when manufacturing production has been buoyant and growth creditable. One such period is that after 2001-02, which, if everything else remained the same, should have contributed to an increase in employment in organized manufacturing between 1993-94 or 1999-2000 and 2004-05.

If this has not happened, it must be because average labour productivity in manufacturing has grown so fast that the effects of the higher rate of increase in output on employment growth would have been more than neutralized. This indeed appears to be the case. According to estimates quoted in the Planning Commission’s Eleventh Plan Document, GDP per worker in manufacturing which grew at 2.29 per cent per annum during 1983 to 1993-94 accelerated to 3.31 per cent between 1993-94 and 2004-05. It is to be expected that this acceleration would have been sharper in the case of organized manufacturing, because of the effects of reform. Prabhat Patnaik argues that the combination of high output growth and low employment growth is a feature characterising many developing countries during the years when they opened their economies to trade and investment. This is because (i) with tastes and preferences of the elite in developing countries being influenced by the “demonstration effect” of lifestyles in the developed countries, new products and processes introduced in the latter very quickly find their way to the developing countries when their economies are opened, and (ii) technological progress in the form of new products and processes in the developed countries is inevitably associated with an increase in labour productivity, so that increased imports of technology imply increased productivity. Hence after trade liberalisation, labour productivity growth in developing countries is exogenously driven and tends to be higher than prior to trade liberalisation, leading to a growing divergence between output and employment growth.

This tendency is exaggerated by the demand-side effects of financial liberalization. One consequence of financial liberalisation and the excess liquidity in the system created by the inflow of foreign capital, has been the growing importance of credit provided to individuals for specific purposes such as purchases of housing property, consumer durables and automobiles of various kinds. Credit has had an important role to play in the expansion of the market for manufactures during the years of reform: through a boom in housing and consumer credit.

An important implication of debt-financed manufacturing demand is that it is inevitably concentrated in the first instance in a narrow range of commodities that are the targets of personal finance. Commodities whose demand is expanded with credit finance vary from construction materials to automobiles and consumer durables. These commodities, which must serve as the collateral for the debt that finances their purchase, must be in the nature of durables and are more-often than not the products of metal- and chemical-based industries and therefore tend to be more capital intensive and are characterised by higher labour productivity.

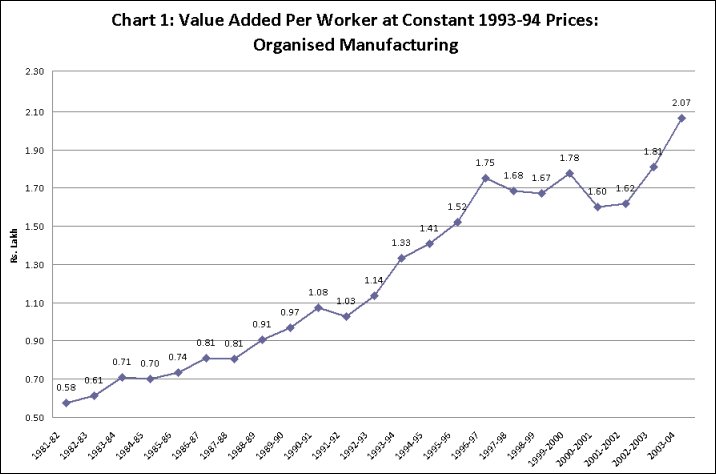

This factor, together with the industrial “restructuring” associated with liberalisation, has resulted in a sharp and persistent increase in labour productivity (as measured by the net value added at constant prices generated per worker) in the organised manufacturing sector during the years of liberalisation. As Chart 1 shows, labour productivity tripled during 1981-82 and 1996-97, stagnated and even slightly declined during the years of the industrial slowdown that set in thereafter, and has once again been rising sharply in the early years of this decade.

It is indeed true that this was expected to some extent given the fact that more than 60 per cent of the increment in GDP in the years after 1991 have come from the services sector, and the manufacturing sector’s share has declined. However, there have been periods when manufacturing production has been buoyant and growth creditable. One such period is that after 2001-02, which, if everything else remained the same, should have contributed to an increase in employment in organized manufacturing between 1993-94 or 1999-2000 and 2004-05.

If this has not happened, it must be because average labour productivity in manufacturing has grown so fast that the effects of the higher rate of increase in output on employment growth would have been more than neutralized. This indeed appears to be the case. According to estimates quoted in the Planning Commission’s Eleventh Plan Document, GDP per worker in manufacturing which grew at 2.29 per cent per annum during 1983 to 1993-94 accelerated to 3.31 per cent between 1993-94 and 2004-05. It is to be expected that this acceleration would have been sharper in the case of organized manufacturing, because of the effects of reform. Prabhat Patnaik argues that the combination of high output growth and low employment growth is a feature characterising many developing countries during the years when they opened their economies to trade and investment. This is because (i) with tastes and preferences of the elite in developing countries being influenced by the “demonstration effect” of lifestyles in the developed countries, new products and processes introduced in the latter very quickly find their way to the developing countries when their economies are opened, and (ii) technological progress in the form of new products and processes in the developed countries is inevitably associated with an increase in labour productivity, so that increased imports of technology imply increased productivity. Hence after trade liberalisation, labour productivity growth in developing countries is exogenously driven and tends to be higher than prior to trade liberalisation, leading to a growing divergence between output and employment growth.

This tendency is exaggerated by the demand-side effects of financial liberalization. One consequence of financial liberalisation and the excess liquidity in the system created by the inflow of foreign capital, has been the growing importance of credit provided to individuals for specific purposes such as purchases of housing property, consumer durables and automobiles of various kinds. Credit has had an important role to play in the expansion of the market for manufactures during the years of reform: through a boom in housing and consumer credit.

An important implication of debt-financed manufacturing demand is that it is inevitably concentrated in the first instance in a narrow range of commodities that are the targets of personal finance. Commodities whose demand is expanded with credit finance vary from construction materials to automobiles and consumer durables. These commodities, which must serve as the collateral for the debt that finances their purchase, must be in the nature of durables and are more-often than not the products of metal- and chemical-based industries and therefore tend to be more capital intensive and are characterised by higher labour productivity.

This factor, together with the industrial “restructuring” associated with liberalisation, has resulted in a sharp and persistent increase in labour productivity (as measured by the net value added at constant prices generated per worker) in the organised manufacturing sector during the years of liberalisation. As Chart 1 shows, labour productivity tripled during 1981-82 and 1996-97, stagnated and even slightly declined during the years of the industrial slowdown that set in thereafter, and has once again been rising sharply in the early years of this decade.

There

are two factors that would have contributed to this sharp increase in

labour productivity. First, there has been an increase in capital-intensity

and labour productivity in individual industries. And, secondly, a faster

rate of increase in demand and production of capital intensive commodities

have resulted in an increase in the share of capital-intensive production

in the total. The shift in the pattern of demand results partly from

the role of credit-financed consumption noted above and partly from

the increases in income inequality that are associated with more liberalized

and open economic regimes.

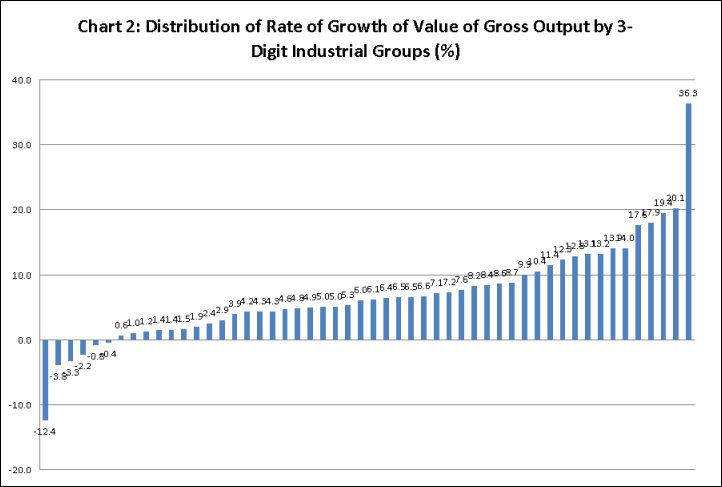

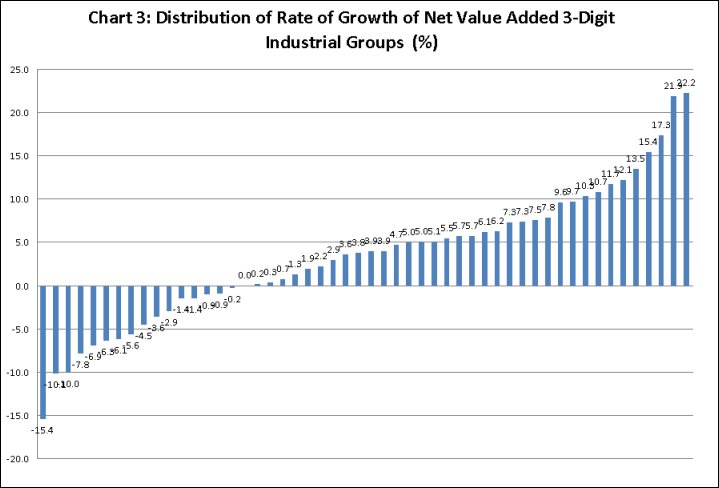

How important have such changes in demand been in the Indian context? Consider Charts 2 and 3, which give the distribution of the trend rates of growth of the real value of output and net value added by 3-digit industry groups in the registered manufacturing sector for the period 1993-94 to 2003-04. It should be clear that there is wide variation in growth performance. A few sectors recorded remarkably high rates of growth, though data problems may be exaggerating figures at the two tails.

Table 1: Growth, Productivity and Capital Intensity

The figures do point to a significant, even if not overwhelmingly strong, relationship between value added growth on the one hand and productivity growth on the other, and a reasonable association between the output/value added variables and average productivity and average capital intensity. Thus the faster growing sectors substantially include those that are characterised by higher rates of growth of productivity and higher capital intensity.

Table 2 provides information on the top 25 3-digit sectors in terms of trend rates of increase in labour productivity among those for which data is available. It should be clear that they cover all of the sectors associated with the credit-financed and inequality-driven household demand boom, suggesting that the pattern of growth associated with the more open and liberalised regime of the 1990s has been significantly responsible for the extremely poor showing in terms of employment growth of an otherwise buoyant organized manufacturing sector.

How important have such changes in demand been in the Indian context? Consider Charts 2 and 3, which give the distribution of the trend rates of growth of the real value of output and net value added by 3-digit industry groups in the registered manufacturing sector for the period 1993-94 to 2003-04. It should be clear that there is wide variation in growth performance. A few sectors recorded remarkably high rates of growth, though data problems may be exaggerating figures at the two tails.

Table 1: Growth, Productivity and Capital Intensity

|

Rank Correlation Coefficient of Rate of Growth

of Net Value Added with |

|

| Average Productivity 1993-94 to 1995-96 |

0.20 |

| Productivity Growth 1993-94 to 2003-04 |

0.48 |

| Average Capital-Labour Ratio 1993-94 to 1995-96 |

0.25 |

Table 2: Top 25 industrial categories in terms of rate of growth of labour productivity

Industry |

Code |

RoG |

| Manufacture of railway and tramway locomotives and rolling stock | 352 | 76.6 |

| Manufacture of coke oven products | 231 | 48.3 |

| Manufacture of watches and clocks | 333 | 41.2 |

| Dressing and dyeing of fur; manufacture of articles of fur | 182 | 21.7 |

| Manufacture of television and radio transmitters and apparatus for line telephony and line telegraphy | 322 | 21.4 |

| Manufacture of glass and glass products | 261 | 20.9 |

| Publishing | 221 | 17.3 |

| Manufacture of motor vehicles | 341 | 15.1 |

| Manufacture of domestic appliances, n.e.c. | 293 | 13.3 |

| Manufacture of other electrical equipment n.e.c. | 319 | 13.0 |

| Manufacture of structural metal products, tanks, reservoirs and steam generators | 281 | 8.8 |

| Manufacture of non-metallic mineral products n.e.c. | 269 | 6.8 |

| Manufacture of refined petroleum products | 232 | 6.4 |

| Manufacture of electric motors, generators and transformers | 311 | 6.4 |

| Manufacture of office, accounting and computing machinery | 300 | 6.1 |

| Manufacture of rubber products | 251 | 6.0 |

| Manufacture of tobacco products | 160 | 5.4 |

| Spinning, weaving and finishing of textiles | 171 | 4.6 |

| Saw milling and planing of wood | 201 | 4.3 |

| Manufacture of paper and paper product | 210 | 4.2 |

| Manufacture of television and radio receivers, sound or video recording or reproducing apparatus, and associated goods | 323 | 4.0 |

| Manufacture of accumulators, primary cells and primary batteries | 314 | 4.0 |

| Manufacture of dairy products | 152 | 3.5 |

| Manufacture of man-made fibers | 243 | 3.4 |

| Production, processing and preservation of meat, fish, fruit vegetables, oils and fats | 151 | 3.1 |

The figures do point to a significant, even if not overwhelmingly strong, relationship between value added growth on the one hand and productivity growth on the other, and a reasonable association between the output/value added variables and average productivity and average capital intensity. Thus the faster growing sectors substantially include those that are characterised by higher rates of growth of productivity and higher capital intensity.

Table 2 provides information on the top 25 3-digit sectors in terms of trend rates of increase in labour productivity among those for which data is available. It should be clear that they cover all of the sectors associated with the credit-financed and inequality-driven household demand boom, suggesting that the pattern of growth associated with the more open and liberalised regime of the 1990s has been significantly responsible for the extremely poor showing in terms of employment growth of an otherwise buoyant organized manufacturing sector.

©

MACROSCAN 2008