Themes > Features

15.10..2008

India and the Global Financial Crisis

When

the financial crisis erupted in a comprehensive manner on Wall Street,

there was some premature triumphalism among Indian policy makers and

media persons. It was argued that India would be relatively immune to

this crisis, because of the “strong fundamentals” of the economy and

the supposedly well-regulated banking system.

This argument was emphasised by the Finance Minister and others even when other developing countries in Asia clearly experienced significant negative impact, through transmission of stock market turbulence and domestic credit stringency. These effects have been most marked among those developing countries where the foreign ownership of banks is already well advanced, and when US-style financial sectors with the merging of banking and investment functions have been created.

If India is not in the same position, it is not to the credit of our policy makers, who had in fact wanted to go along the same route. Indeed, for some time now there have been complaints that these “necessary” reforms which would “modernise” the financial sector have been held up because of opposition from the Left parties.

But even though we are slightly better protected from financial meltdown, largely because of the still large role of the nationalised banks and other controls on domestic finance, there is certainly little room for complacency. The recent crash in the Sensex is not simply an indicator of the impact of international contagion. There have been warning signals and signs of fragility in Indian finance for some time now, and these are likely to be compounded by trends in the real economy.

After a long spell of growth, the Indian economy is experiencing a downturn. Industrial growth is faltering, inflation remains at double-digit levels, the current account deficit is widening, foreign exchange reserves are depleting and the rupee is depreciating.

The last two features can also be directly related to the current international crisis. The most immediate effect of that crisis on India has been an outflow of foreign institutional investment from the equity market. Foreign institutional investors, who need to retrench assets in order to cover losses in their home countries and are seeking havens of safety in an uncertain environment, have become major sellers in Indian markets.

In 2007-08, net FII inflows into India amounted to $20.3 billion. As compared with this, they pulled out $11.1 billion during the first nine and half months of calendar year 2008, of which $8.3 billion occurred over the first six and a half months of financial year 2008-09 (April 1 to October 16). This has had two effects: in the stock market and in the currency market.

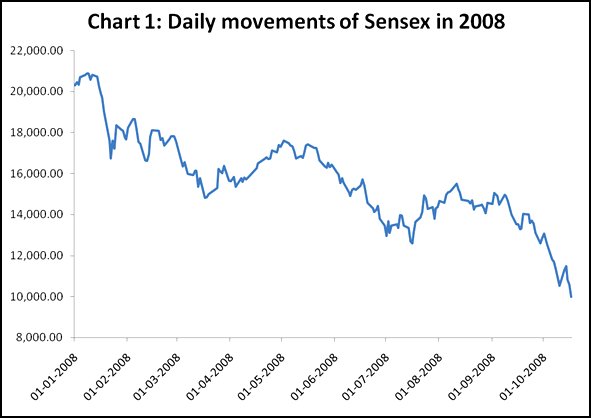

Given the importance of FII investment in driving Indian stock markets and the fact that cumulative investments by FIIS stood at $66.5 billion at the beginning of this calendar year, the pull-out triggered a collapse in stock prices. As a result, the Sensex fell from its closing peak of 20,873 on January 8, 2008 to less than 10,000 by 17 October 2008 (Chart 1).

This argument was emphasised by the Finance Minister and others even when other developing countries in Asia clearly experienced significant negative impact, through transmission of stock market turbulence and domestic credit stringency. These effects have been most marked among those developing countries where the foreign ownership of banks is already well advanced, and when US-style financial sectors with the merging of banking and investment functions have been created.

If India is not in the same position, it is not to the credit of our policy makers, who had in fact wanted to go along the same route. Indeed, for some time now there have been complaints that these “necessary” reforms which would “modernise” the financial sector have been held up because of opposition from the Left parties.

But even though we are slightly better protected from financial meltdown, largely because of the still large role of the nationalised banks and other controls on domestic finance, there is certainly little room for complacency. The recent crash in the Sensex is not simply an indicator of the impact of international contagion. There have been warning signals and signs of fragility in Indian finance for some time now, and these are likely to be compounded by trends in the real economy.

After a long spell of growth, the Indian economy is experiencing a downturn. Industrial growth is faltering, inflation remains at double-digit levels, the current account deficit is widening, foreign exchange reserves are depleting and the rupee is depreciating.

The last two features can also be directly related to the current international crisis. The most immediate effect of that crisis on India has been an outflow of foreign institutional investment from the equity market. Foreign institutional investors, who need to retrench assets in order to cover losses in their home countries and are seeking havens of safety in an uncertain environment, have become major sellers in Indian markets.

In 2007-08, net FII inflows into India amounted to $20.3 billion. As compared with this, they pulled out $11.1 billion during the first nine and half months of calendar year 2008, of which $8.3 billion occurred over the first six and a half months of financial year 2008-09 (April 1 to October 16). This has had two effects: in the stock market and in the currency market.

Given the importance of FII investment in driving Indian stock markets and the fact that cumulative investments by FIIS stood at $66.5 billion at the beginning of this calendar year, the pull-out triggered a collapse in stock prices. As a result, the Sensex fell from its closing peak of 20,873 on January 8, 2008 to less than 10,000 by 17 October 2008 (Chart 1).

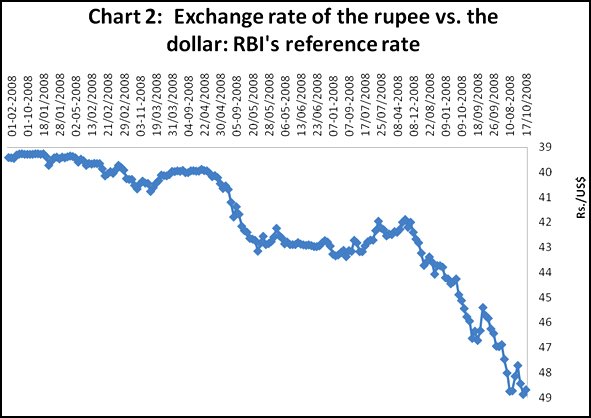

In

addition, this withdrawal by the FIIs led to a sharp depreciation of

the rupee. Between January 1 and October 16, 2008, the RBI reference

rate for the rupee fell by nearly 25 per cent, even relative to a weak

currency like the dollar, from Rs. 39.20 to the dollar to Rs. 48.86

(Chart 2). This was despite the sale of dollars by the RBI, which was

reflected in a decline of $25.8 billion in its foreign currency assets

between the end of March 2008 and October 3, 2008.

While these trends are still in process, their effects are already being felt. They are not the only causes for the downturn the economy is experiencing, but they are important contributory factors. Yet, this does not justify the argument that India’s difficulties are all imported. They are induced by domestic policy as well.

The extent of imported difficulties would have been far less if the government had not increased the vulnerability of the country to external shocks by drastically opening up the real and financial sectors. It is disconcerting, therefore, that when faced with this crisis the government is not rethinking its own liberalisation strategy, despite the backlash against neoliberalism worldwide. By deciding to relax conditions that apply to FII investments in the vain hope of attracting them back and by focusing on pumping liquidity into the system rather than using public expenditure and investment to stall a recession, it is indicating that it hopes that more of what created the problem would help solve it. This is just to postpone decisions that may prove critica-till it is too late.

It

could be argued that the $275 billion the RBI still has in its kitty

is adequate to stall and reverse any further depreciation if needed.

But, given the sudden exit by the FIIs, the RBI is clearly not keen

to deplete its reserves too fast and risk a foreign exchange crisis.

The result has been the observed sharp depreciation of the rupee.

While this depreciation may be good for India’s exports that are adversely

affected by the slowdown in global markets, it is not so good for

those who have accumulated foreign exchange payment commitments. Nor

does it assist the government’s effort to rein in inflation.

A second route through which the global financial crisis could affect India is through the exposure of Indian banks or banks operating in India to the impaired assets resulting from the subprime crisis. Unfortunately, there are no clear estimates of the extent of that exposure, giving room for rumour in determining market trends. Thus, ICICI Bank was the victim of a run for a short period because of rumours that subprime exposure had badly damaged its balance sheet, although these rumours have been strongly denied by the bank.

So far the RBI has claimed that the exposure of Indian banks to assets impaired by the financial crisis is small. According to reports, the RBI had estimated that as a result of exposure to collateralised debt obligations and credit default swaps, the combined mark-to-market losses of Indian banks at the end of July was around $450 million. Given the aggressive strategies adopted by the private sector banks, the MTM losses incurred by public sector banks were estimated at $90 million, while that for private banks was around $360 million. As yet these losses are on paper, but the RBI believes that even if they are to be provided for, these banks are well capitalised and can easily take the hit.

Such assurances have neither reduced fears of those exposed to these banks or to investors holding shares in these banks. These fears are compounded by those of the minority in metropolitan areas dealing with foreign banks that have expanded their presence in India, whose global exposure to toxic assets must be substantial. What is disconcerting is the limited information available on the risks to which depositors and investors are subject. Only time will tell how significant this factor will be in making India vulnerable to the global crisis.

A third indirect fall-out of the global crisis and its ripples in India is in the form of the losses sustained by non-bank financial institutions (especially mutual funds) and corporates, as a result of their exposure to domestic stock and currency markets. Such losses are expected to be large, as signalled by the decision of the RBI to allow banks to provide loans to mutual funds against certificates of deposit (CDs) or buy-back their own CDs before maturity. These losses are bound to render some institutions fragile, with implications that would become clear only in the coming months.

A fourth effect is that, in this uncertain environment, banks and financial institutions concerned about their balance sheets, have been cutting back on credit, especially the huge volume of housing, automobile and retail credit provided to individuals. According to RBI figures (reported by the Business Standard, 17 October 2008), the rate of growth of auto loans fell from close to 30 per cent over the year ending June 30, 2008 as low as 1.2 per cent. Loans to finance consumer durables purchases fell from around Rs 6,000 crore in the year to June 2007, to a little over Rs 4,000 crore up to June this year. Direct housing loans, which had increased by 25 per cent during 2006-07, decelerated to 11 per cent growth in 2007-08 and 12 per cent over the year ending June 2008.

It is only in an area like credit-card receivables, where banks are unable to control the growth of credit, that expansion was, at 43 per cent, quite high over the year ending June 2008, even though it was lower than the 50 per cent recorded over the previous year.

It is known that credit-financed housing investment and credit-financed consumption have been important drivers of growth in recent years, and underpin the 9 per cent growth trajectory India has been experiencing. The reticence of lenders to increase their exposure in markets to which they are already overexposed and the fears of increasing payment commitments in an uncertain economic environment on the part of potential borrowers are bound to curtail debt-financed consumption and investment. This could slow growth significantly.

Table 1: Retail Credit Growth

Finally,

the recession generated by the financial crisis in the advanced economies

as a group and the United States in particular, will adversely affect

India’s exports, especially its exports of software and IT-enabled services,

more than 60 per cent of which are directed to the United States. International

banks and financial institutions in the US and EU are important sources

of demand for such services, and the difficulties they face will result

in some curtailment of their demand. Further, the nationalisation of

many of these banks is likely to increase the pressure to reduce outsourcing

in order to keep jobs in the developed countries. And the slowing of

growth outside of the financial sector too will have implications for

both merchandise and services exports. The net result would be a smaller

export stimulus and a widening trade deficit.A second route through which the global financial crisis could affect India is through the exposure of Indian banks or banks operating in India to the impaired assets resulting from the subprime crisis. Unfortunately, there are no clear estimates of the extent of that exposure, giving room for rumour in determining market trends. Thus, ICICI Bank was the victim of a run for a short period because of rumours that subprime exposure had badly damaged its balance sheet, although these rumours have been strongly denied by the bank.

So far the RBI has claimed that the exposure of Indian banks to assets impaired by the financial crisis is small. According to reports, the RBI had estimated that as a result of exposure to collateralised debt obligations and credit default swaps, the combined mark-to-market losses of Indian banks at the end of July was around $450 million. Given the aggressive strategies adopted by the private sector banks, the MTM losses incurred by public sector banks were estimated at $90 million, while that for private banks was around $360 million. As yet these losses are on paper, but the RBI believes that even if they are to be provided for, these banks are well capitalised and can easily take the hit.

Such assurances have neither reduced fears of those exposed to these banks or to investors holding shares in these banks. These fears are compounded by those of the minority in metropolitan areas dealing with foreign banks that have expanded their presence in India, whose global exposure to toxic assets must be substantial. What is disconcerting is the limited information available on the risks to which depositors and investors are subject. Only time will tell how significant this factor will be in making India vulnerable to the global crisis.

A third indirect fall-out of the global crisis and its ripples in India is in the form of the losses sustained by non-bank financial institutions (especially mutual funds) and corporates, as a result of their exposure to domestic stock and currency markets. Such losses are expected to be large, as signalled by the decision of the RBI to allow banks to provide loans to mutual funds against certificates of deposit (CDs) or buy-back their own CDs before maturity. These losses are bound to render some institutions fragile, with implications that would become clear only in the coming months.

A fourth effect is that, in this uncertain environment, banks and financial institutions concerned about their balance sheets, have been cutting back on credit, especially the huge volume of housing, automobile and retail credit provided to individuals. According to RBI figures (reported by the Business Standard, 17 October 2008), the rate of growth of auto loans fell from close to 30 per cent over the year ending June 30, 2008 as low as 1.2 per cent. Loans to finance consumer durables purchases fell from around Rs 6,000 crore in the year to June 2007, to a little over Rs 4,000 crore up to June this year. Direct housing loans, which had increased by 25 per cent during 2006-07, decelerated to 11 per cent growth in 2007-08 and 12 per cent over the year ending June 2008.

It is only in an area like credit-card receivables, where banks are unable to control the growth of credit, that expansion was, at 43 per cent, quite high over the year ending June 2008, even though it was lower than the 50 per cent recorded over the previous year.

It is known that credit-financed housing investment and credit-financed consumption have been important drivers of growth in recent years, and underpin the 9 per cent growth trajectory India has been experiencing. The reticence of lenders to increase their exposure in markets to which they are already overexposed and the fears of increasing payment commitments in an uncertain economic environment on the part of potential borrowers are bound to curtail debt-financed consumption and investment. This could slow growth significantly.

Table 1: Retail Credit Growth

| In Rs Crore | Year up to June |

Year

on Year Growth in per cent |

|

| 2007 |

2008 |

||

|

Housing

Loans |

230,700 | 259,000 | 12.27 |

|

Personal

Loans |

161,000 | 193,000 | 19.88 |

|

Auto

Loans |

86,000 | 87,000 | 1.16 |

| Credit Card Receivables | 21,000 | 30,000 | 42.86 |

| Consumer Durables | 6,000 | 4,000 | -33.33 |

| Source: Business Standard 17 October 2008, Section II, Page 1. | |||

While these trends are still in process, their effects are already being felt. They are not the only causes for the downturn the economy is experiencing, but they are important contributory factors. Yet, this does not justify the argument that India’s difficulties are all imported. They are induced by domestic policy as well.

The extent of imported difficulties would have been far less if the government had not increased the vulnerability of the country to external shocks by drastically opening up the real and financial sectors. It is disconcerting, therefore, that when faced with this crisis the government is not rethinking its own liberalisation strategy, despite the backlash against neoliberalism worldwide. By deciding to relax conditions that apply to FII investments in the vain hope of attracting them back and by focusing on pumping liquidity into the system rather than using public expenditure and investment to stall a recession, it is indicating that it hopes that more of what created the problem would help solve it. This is just to postpone decisions that may prove critica-till it is too late.

©

MACROSCAN 2008