Themes > Features

09.09.2003

Does The New WTO Drugs Deal Really Benefit Developing Countries?

On 30 August 2003, just before the negotiating teams at the WTO in Geneva

went back to their respective countries to prepare for the Ministerial

Meeting at Cancun, the deadlock over intellectual property and public

health was finally broken. The TRIPs Council agreed on legal changes that

are officially supposed to make it easier for poorer countries to import

cheaper generics made under compulsory licensing if they are unable to

manufacture the medicines themselves.

The decision settled the one piece of unfinished business on intellectual

property and health that remained from the WTO Ministerial Conference in

Doha in November 2001, and which had been left hanging for the previous

months because of fierce resistance from the

US government and the multinational lobby.

The decision was

immediately hailed by some and described as a great victory for the

developing countries and indeed for the people of the world. ‘This is a

historic agreement for the WTO’, said the WTO Director-General Supachai

Panitchpakdi. ‘The final piece of the jigsaw has fallen into place,

allowing poorer countries to make full use of the flexibilities in the

WTO’s intellectual property rules in order to deal with the diseases that

ravage their people. It proves once and for all that the organization can

handle humanitarian as well as trade concerns.’

However, the actual details of the agreement suggest that such extravagant

and fulsome praise may be uncalled for. In fact, many independent

analysts, along with the NGOs and civil society groups that had been

fighting for an agreement on this issue, feel betrayed by the final

character of the resolution, and have argued that it will do little or

nothing to improve the situation for people in the developing countries in

terms of accessing cheaper life-saving drugs.

Thus, James Love of the Consumer Project on Technology has written that

‘the persons who have negotiated this agreement have given the world a new

model for explicitly endorsing protectionism.’ Oxfam and Medecin sans

Frontieres, two groups who have closely followed the negotiations, have

called the solution ‘unworkable’ saying that the ‘deal was designed to

offer comfort to the US and the western pharmaceutical industry’ and that

‘global patent rules will continue to drive up the price of medicines’.

It is even possible to argue that the final form of the resolution is

actually a step backward compared to the flexibilities that existed in the

original TRIPs agreement, and that the entrenched position of the large

international drug monopolies is further legalized by the recent

statement. However, to understand this, it is necessary to provide some

background on both the international pharmaceuticals industry, and the

TRIPs agreement and the controversies that have surrounded it.

The International Pharma Industry

Pharmaceutical markets

differ from markets for most other commodities, since drugs are rather

special commodities. Private drug markets typically suffer from a number

of forms of market failure. These include: (a) informational

imbalances—thus, for example, consumers are not in a position to judge the

quality and efficacy of drugs, which creates the need for a social

monitoring and surveillance system; (b) monopoly and lack of competition

created by patent protection, brand loyalty and market segmentation; (c)

externalities in the form of social benefits of drug consumption. Drugs

play a significant social role in that they are an integral part of the

realization of the fundamental human right to health. For these reasons,

pharmaceutical products are classified as essential goods, with the

understanding that they have to be accessible to all people.

Obviously, access to the latest available technology in this sphere is

crucially important for the health and welfare of children, not only in

terms of availability to all children but also the access of mothers.

There is clear need for some social control over investment in technology

relating to drug production, and the subsequent prices and distribution,

not only because of the market failures described above, but also since

unregulated drug markets tend to create substantial inequity, particularly

in terms of access to drugs.

The world market for drugs is a huge one, but it is dominated by only

three countries—the

United States,

Japan and Germany—which account for more than two-thirds of total sales.

In fact, only 15 per cent of the world's population accounts for 86 per

cent of drug spending, while the remaining 85 per cent get only a 14 per

cent share.

The difficulty of ensuring even a minimum degree of democratic access to

life-saving drugs is compounded by the high degree of concentration in the

international drug industry. Table 1 describes the situation in 1998, when

the top ten companies controlled 36 per cent of the market and the top

twenty companies controlled 57 per cent of world sales.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since then there have been more mega-mergers which have made the industry

even more concentrated. Glaxo Wellcome merged with SmithKline Beecham,

Pfizer merged with Warner Lambert, and the companies Hoechst-Marion,

Merrell and Rhone-Poulenc merged to form Aventis. Currently the top ten

companies are estimated to control more than half of the world market, and

the top twenty companies more than two-thirds of the world market.

Apart from mergers, there is growing evidence that drug companies are

using the patent system to establish monopoly control. Often patents are

filed for products or chemical substances, or now even genes, whose

attributes are not fully known, simply to pre-empt the competition and

allow for monopoly rents once further research—possibly by others

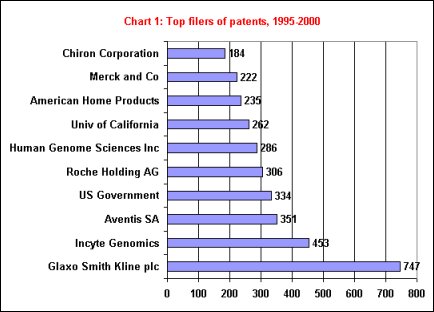

including public agencies—reveals the uses. As Table 2 shows, the top ten

filers of patents include six drug companies and two companies

specializing in genetic research.

Such monopoly allows drug companies to charge prices

that are as high as they feel the market will bear, without reference to

or well in excess of the actual costs of R&D that they may have borne.

Thus there is wide variation in prices of the same drug charged not only

by different companies but even by the same company in different markets.

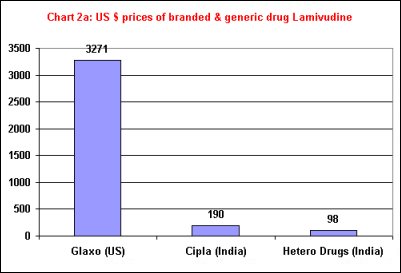

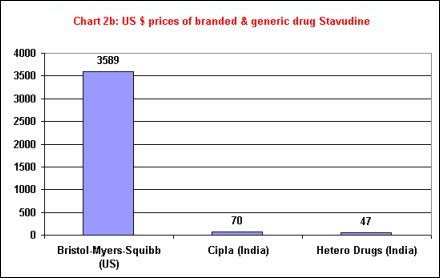

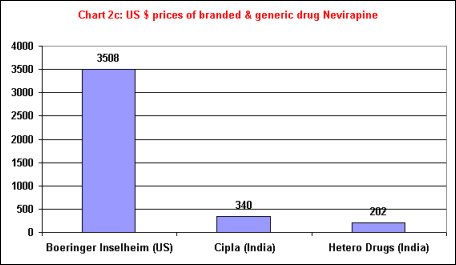

As Charts 2a, 2b and 2c, show, the prices

of branded or patented products are often far higher than the prices of

similar medicines produced by alternative or generic sources.

The use of market

segmentation to earn monopoly profits is obviously constrained by the

possibility of undercutting by competitors producing generic substitutes.

This possibility, and the opposition of multinational drug companies to

allowing it, was dramatically illustrated by the battle between the Indian

drug company Cipla and major MNC players over providing cheaper drugs for

AIDS patients in Africa.

The fact that

competition

from generic producers will result in the lowering and levelling of prices

of medicines is very clear even from the pricing behaviour of large

multinational drug companies in different markets. Not only do MNCs price

differently in different markets, but they tend to charge much less when

generic drug substitutes are available.

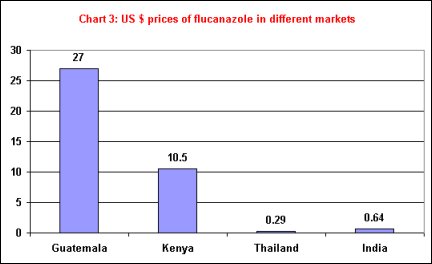

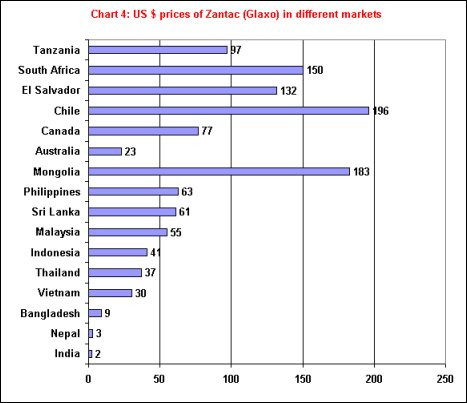

This is sharply evident

from Chart 3, which shows prices of Flucanazole in different markets, and

Chart 4, which indicates the different prices charged by Glaxo for its

anti-ulcer drug Zantac. Such pricing bears little relation to per capita

income in the country concerned, but is much more dependent upon the

existence of generic substitutes like Ranitidine, which is why the drug is

the cheapest in

India.

The TRIPS Agreement

This context explains

why there have been major concerns about the enforcement of the TRIPs

agreement, particularly with reference to health conditions in developing

countries, since the agreement is seen as increasing the power of large

corporations who may be in a position to capture patents, vis-à-vis state

regulatory authorities.

The agreement requires all WTO member states to grant patents for

pharmaceutical products or process inventions for a minimum of twenty

years. The major shift for countries like India was that the TRIPs

agreement forces upon member countries a patent regime that recognizes

product patents for chemicals and pharmaceuticals. The earlier Indian

Patent Act allowed for only process patents in these areas, which created

the possibility of reverse engineering especially for drugs, a factor that

was crucial in the rapid development of the generic drug industry in

India.

Some of the most frequently expressed concerns about the adverse

implications of TRIPs for public health include the following:

-

Increased patent protection leads to higher drug prices, while the number of patented drugs of importance from a public health point of view is likely to increase in the coming years.

-

The access gap between developed and developing countries, and between rich and poor in all countries, will continue to increase, especially as producers in developing countries have to wait for twenty years before they can have access to innovations.

-

Enforcement of the WTO regulations has an effect on local manufacturing capacity and removes a source of generic innovative quality drugs on which the poorer countries depend.

-

While technology transfer is actually to be discouraged, there are no incentives or provisions to ensure that increased revenues will go towards the development of essential medical technologies.

It is now much more widely recognized that there is no necessary correlation between socially desirable and necessary R&D in drug development, and a tight patent regime. Indeed, much of the major research in pharmaceuticals and medicine, both in the past and currently, is under the aegis of publicly funded institutions across the world. Table 2 indicates that R&D expenditure forms a relatively small part of the total revenues for large pharma companies, and is significantly less than marketing expenses. It is also worth noting that even in many western countries, pharmaceutical products remained unpatentable until the 1980s or even the 1990s, with no adverse implications for research.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, even this restrictive agreement did leave

member states a certain amount of freedom in modifying their regulations.

For example, the terms

invention

and discovery

are not defined in the agreement, yet how they are defined could have

important implications, especially in the biotechnology field. The

agreement says that member states may provide limited exceptions to the

patent holder’s exclusive rights in their laws.

National public authorities may be allowed, within the conditions laid

down in the agreement, to issue compulsory licences against the patent

owner’s will when justified by the public interest. The agreement does

not prohibit parallel imports. These restore price competition for

patented products by allowing the importation (without the holder’s

consent) of identical patented products which have been manufactured for a

lower price in another country.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Thus, compulsory licensing and parallel importing policies are two policy tools which can still play an important role in helping developing country governments make essential medicines more affordable to their citizens, although their use is being sought to be restricted by drug MNCs and their home country governments.

Compulsory Licensing

Compulsory licensing

may occur as follows: when reasons of general interest justify it,

national public authorities may allow the exploitation of a patent by a

third person without the owner’s consent. This involves a government

giving a manufacturer—which could be a company, government agency or other

party—a licence to produce a drug for which another company holds a

patent, in exchange for the payment of a reasonable royalty to the patent

holder. The effect is to introduce generic competition and drive prices

down, as has occurred in India. Compulsory licensing can lower the prices

of medicines by 75 per cent or more. Zimbabwe, for example, could issue a

license to a local company for an HIV/AIDS drug manufactured by

Bristol-Myers Squibb. The Zimbabwean firm would then manufacture the drug

for sale in Zimbabwe under a generic name, and pay a reasonable royalty to

Bristol-Myers Squibb on each sale.

Five kinds of use without authorization of the right holder are expressly

envisaged by the agreement [Correa 1999, 2000]:

-

licences for public non-commercial use by the Government;

-

licences granted to third parties authorised by the Government for public non-commercial use;

-

licences granted in conditions of emergency or extreme urgency;

-

licences granted to remedy a practice determined after administrative or judicial process to be anti-competitive;

-

licences arising from a dependent patent.

In addition, since the

agreement does not state that these are the only cases authorized, member

states are not limited in regard to the grounds on which they may decide

to grant a licence without the authorization of the patent holder. They

are in practice only limited in terms of the procedure and conditions to

be followed. Thus, in principle, compulsory licences can be issued for

considerations of public health as well as to prevent anti-competitive

practices and possible uses connected with monopoly.

Parallel Imports

Another strategy for

lowering drug prices is by parallel imports. Parallel importing involves a

government or another importer shopping in the world market for the lowest

priced version of a drug rather than accepting the price at which it is

sold in their country. In the pharmaceutical market, as has been shown,

prices tend to vary dramatically. Since parallel imports involve imports

of a product from one country and resale, without authorization of the

original seller, in another, thereby allowing the buyer to search for the

lowest world price, they can also be a tool to enable developing countries

to lower prices for consumers.

Both the promotion and the transfer of technology, as well as public

health or nutrition could justify derogation of the patentee's exclusive

rights. Scrutiny of the exceptions existing in much national legislation

gives an idea of the different possibilities [Correa, 1999]:

-

parallel importation of the protected product;

-

acts carried out on a private basis and for non-commercial purposes;

-

scientific research and experiments involving the patented invention;

-

preparation of drugs by unit and on medical prescription in pharmacy dispensaries;

-

a person being, in good faith, already in possession of the invention covered by the patent;

-

tests carried out before the expiry of the patent to establish the bio-equivalence of a generic drug.

In addition to these measures, as pointed by Correa [2000], there is scope within the TRIPs Agreement (under Article 30) for a number of exceptions to exclusive patent rights. Such exceptions must of course meet certain conditions: that is, they must be limited, they should not unreasonably conflict with the normal exploitation of the patent, and exceptions should not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner. Given these conditions, there is a wide range of exceptions that can be provided that are within the scope of Article 30, such as:

- acts done privately and/or on a non-commercial scale, or for a non-commercial purpose

- use of the invention for research

- use of the invention for teaching purposes

- experimentation for teaching purposes

- preparation of medicines under individual prescriptions

- experiments made for the purpose of seeking regulatory approval for marketing of a product after the expiry of a patent

- use of the invention by a third party that had used it bona fide before the date of application of the patent.

As can be seen, even

though the TRIPs provisions were restrictive, governments that were

anxious to ensure drug development for public health purposes could still

endeavour to push for more flexible patent regimes, if they were not

prevented from doing so by other forces. The problem was, of course, that

many developing country governments have found it difficult to implement

the more flexible provisions because of other kinds of external pressure.

The US government and other developed country governments, in particular,

because of their own large drug lobbies like phaRMa, have been

aggressively restricting governments that have or had intellectual

property rules such as compulsory licensing and parallel imports, designed

to make essential medicines more affordable to their citizens.

The Debate on TRIPS and Public Health in the WTO

This is why developing

countries were keen on explicit recognition in the WTO that public health

requirements could permit the legal implementation of loopholes that

already existed in the TRIPs document. All the subsequent activity has

been devoted to nothing more ambitious than a restatement of that basic

right.

Developing countries were essentially seeking a declaration recognizing

their right to implement certain pro-competitive measures, notably

compulsory licences and parallel imports, as needed to enhance access to

health care. They were frustrated by the opposition and pressure exerted

on some countries by the pharmaceutical industry and governments.

Moreover, some felt that the final proviso in Article 8.1 establishing

that any measures adopted,

inter alia, to protect public health should be consistent with the

provisions of the TRIPs agreement, provided

less

protection for public health than under the corresponding exceptions of

Article XX (b) of GATT and the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and

Technical Barriers to Trade agreements.

TRIPs Article 8.1 states: ‘Members may, in formulating or amending their

laws and regulations, adopt measures necessary to protect public health

and nutrition, and to promote the public interest in sectors of vital

importance to their socio-economic and technological development, provided

that such measures are consistent with the provisions of this Agreement.’

The GATT Article XX: ‘Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to

prevent the adoption or enforcement by any contracting party of measures

necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health.’

The Doha declaration on TRIPs and public health was the first step towards

the restatement of such rights. It stated that ‘Each Member has the right

to grant compulsory licences and the freedom to determine the grounds upon

which such licences are granted’, and that ‘Each Member has the right to

determine what constitutes a national emergency or other circumstances of

extreme urgency, it being understood that public health crises, including

those relating to HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other epidemics, can

represent a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency.’

However, the agreement did not specify conditions for parallel imports,

instead providing the now-infamous Paragraph 6, which ran as follows: ‘We

recognize that WTO Members with insufficient or no manufacturing

capacities in the pharmaceutical sector could face difficulties in making

effective use of compulsory licensing under the TRIPs Agreement. We

instruct the Council for TRIPs to find an expeditious solution to this

problem and to report to the General Council before the end of 2002.’

If the WTO establishment had been serious about fulfilling this promise,

the most straightforward way would have been for the exporting country to

make a limited exception from the patent privilege under Article 30. It is

noteworthy that so far the developed countries have succeeded in forcing

the discussion in the TRIPs Council away from the possibilities inherent

in Article 30 of the TRIPs agreement, which were discussed above. Instead,

they have focussed on Article 31, which is much more limited, constraining

and cumbersome.

The basic statement, which was finally cleared on 30 August, had actually

been formulated in 2001, but was held up by the US government on behalf of

its Big PhaRMA lobby (which incidentally had generously funded the Bush

and Republican election campaigns). The modified version that is now

cleared, has put in many more restrictions which drastically limit the

ability of importing countries to access cheaper generic substitutes, and

therefore contain the ability of such generic manufacturers to benefit

from economies of scale and emerge as real competitors of the large drug

companies.

All that the new statement does is waive the obligations of the exporting

country under Article 31(f) of the TRIPs agreement with respect to the

grant by it of a compulsory licence to a company, which was supposed to be

for the domestic market only. Export can be permitted to importing

countries that fulfil the following conditions.

First, the eligible importing member can only be a least developed

country or a developing country that does not have adequate facilities to

produce the drug in question. This importing country has to make a

notification to the TRIPs Council that:

- specifies the names and expected quantities of the products needed;

- confirms that the eligible importing Member in question, (other than a least developed country Member) has established that it has insufficient or no manufacturing capacities in the pharmaceutical sector for the products in question in one of various ways are which specified; and

- confirms that, where a pharmaceutical product is patented in its territory, it has granted or intends to grant a compulsory licence in accordance with Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement and the provisions of this decision.

Importing countries

also have to ensure legal administrative means of preventing

re-exportation of any such drugs.

Similarly, the compulsory licence issued by the exporting member

has to contain the following conditions:

- only the amount necessary to meet the needs of the eligible importing Member(s) may be manufactured under the licence and the entirety of this production shall be exported to the Member(s) which has notified its needs to the Council for TRIPS;

- products produced under the licence shall be clearly identified as being produced under the system set out in this Decision through specific labelling or marking. Suppliers should distinguish such products through special packaging and/or special colouring/shaping of the products themselves, provided that such distinction is feasible and does not have a significant impact on price; and

- before shipment begins, the licensee shall post on a website information relating to the quantities being supplied to each destination and the distinguishing features of the products;

- (c) the exporting Member has to notify the TRIPS Council of the grant of the licence, including the conditions attached to it. The information provided has to include the name and address of the licensee, the products for which the licence has been granted, the quantities for which it has been granted, the countries to which the products are to be supplied and the duration of the licence, and the address of the relevant website.

It is amazing that the same developing countries which had been clamouring for a quick and fair resolution of the problem, have agreed to a decision that is so patently imbalanced in favour of large multinational patent holders, so restrictive and so unworkable for exporters and importers of generic drugs. The suspicion must be that this agreement, which had been held up for so long by the developed countries (especially the US) and the multinational drug lobby, has now been hammered down the throats of the unfortunate developing country negotiators, simply in order to show some results before the Cancun Meeting. If this is so, it certainly augurs badly for the outcome of other trade negotiations in Cancun.

© MACROSCAN

2003