How is Indian Industry Faring?

With

outsourcing of services emerging the employment issue of the times,

the performance of India's services sector is under scrutiny. In a recent

article in the Financial Times (September 1, 2004), Stephen Roach, the

chief economist of Morgan Stanley declared: ''The impetus that services

have given to India's growth has been … impressive. The services portion

of India's GDP increased from 40.6 per cent in 1990 to 50.8 per cent

in 2003 – accounting for 62 per cent of the cumulative increase in GDP.''

There is one important problem with such an assessment. It often tends

to generalise the dynamism, albeit from a small base, of IT-enabled

and software services to the services sector as a whole. As

Table 1 indicates,

the services share in GDP increased by close to 9 percentage points

between 1990-91 and 2001-02, which was much higher than increases during

earlier decades. But a decomposition of that increase suggests (i) that

public administration and defence was an insignificant contributor to

that increase contrary to the belief in some quarters; and (i) the increase

was almost equally due to Trade, hotels and restaurants, Transport,

storage and communications and Financing, insurance and real estate

Table

1: Percentage points Change in Shares in GDP of Selected Services |

|||||

|

1950-51

TO 60-61 |

1960-61

TO 1970-71 |

1970-71

TO 80-81 |

1980-81

TO 90-91 |

1990-91

TO 2001-02 |

|

Trade,

hotels & restaurant |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

0.4 |

2.5 |

Transport,storage

& comm. |

0.6 |

0.7 |

1.6 |

0.0 |

2.2 |

Financing,ins.,

real estate & business services |

-0.6 |

-0.2 |

0.6 |

3.2 |

2.8 |

Community,social

& personal services |

-0.2 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

Public

administration & defence |

0.3 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

Services |

1.0 |

3.2 |

4.4 |

4.0 |

8.9 |

The

first of these features is positive inasmuch as it indicates that services

growth is not just a fall-out of rising government expenditure. However,

the second suggests that there has been a generalised expansion in private

services. This suggests that assessments based on the aggregate services

figure do not take full account of the nature of the expansion of the

services sector, separating out the more dynamic elements epitomised

by IT-enabled and financial services from segments that could reflect

the distress-driven spill over into services activities of a population

driven out of land and not absorbed by industry.

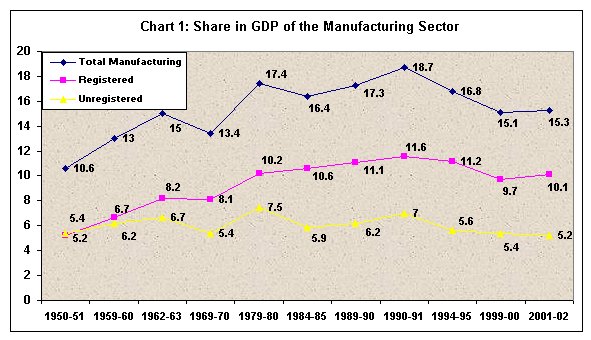

The possibility that the latter is an important influence on the growth

of services arises from the growing evidence that the commodity producing

sectors, viz. agriculture and manufacturing are either in crisis or

performing poorly. Consider for example the manufacturing component

of the industrial sector. Its share in GDP (Chart

1)

has

fallen during the second half of the 1990s and immediately thereafter.

And that fall has characterised both the registered and unregistered

manufacturing sector. Given the fact that the share of manufacturing

in India was already smaller than in many other successful developing

countries, this trend should give cause for concern. In fact this has

led some economists like Vijay Joshi of Oxford University to argue (Business

Standard September 2, 2004) that even though India features among the

world's top growth performers during the last two decades, the character

of that growth ''raises doubts about whether it can be maintained at

its present rate''.

However, overall such concern has been limited, if not altogether missing,

for a number of reasons. Post-liberalisation, there has been a substantial

increase in the extent of ''product innovation'' or availability of

new manufactured goods in the Indian market. International firms that

were permitted limited entry into the Indian market prior to liberalisation

are increasingly visible in recent times. Profit figures of some Indian

manufacturing firms suggest that they are in robust health. And official

figures of the growth of manufacturing output point to a substantial

degree of buoyancy in the manufacturing sector.

However, many of these are superficial indicators of industrial performance.

Product innovation could be accompanied by a decline in domestic value

added, because of a rise in the import intensity of domestic production.

Transnational firms could be displacing domestic production or acquiring

Indian firms rather than contributing to any net increase in output.

And higher profits for a few may be accompanied by lower profits or

losses for the majority. What is more, the profitability of at least

some of the successful firms could be due to ''other income'' from activities

outside manufacturing, especially their participation in financial activities.

The real indicators of performance, therefore, are the actual figures

of trends in production. Unfortunately, close scrutiny of these figures

does not provide a satisfactory answer. As

Table 2 shows, the lead indicator of industrial performance, the

Index of Industrial Production, suggests that after close to two decades

of depressed growth, the trend rate of growth of manufacturing recovered

to 6.1 per cent during the decade starting in 1985-86. That rate of

growth was indeed creditable, even if below that touched during the

decade-and-a-half immediately after the launch of planned development.

Further, this creditable rate of growth of manufacturing appears to

have been sustained during the subsequent years as well.

Table

2: Annual Trend Rates of Growth based on the IIP |

||||

|

Total |

Manf. |

Min.

& Qu. |

Elect. |

|

1950-51

to 64-65 (a) |

7.2 |

7.1 |

5.9 |

13.6 |

1965-66

to 79-80 (b) |

4.7 |

3.8 |

6.9 |

6.2 |

1965-66

to 74-75 (b) |

4.3 |

2.7 |

9.4 |

3.8 |

1975-76

to 84-85 (c) |

4.9 |

4.3 |

6.6 |

7.3 |

1985-86

to 94-95 (d) |

6.2 |

6.2 |

4.2 |

8.3 |

1994-95

to 03-04 (e) |

5.7 |

6.1 |

2.6 |

5.3 |

Notes:

a) Based on series with base 1950-51 =100

b) Based on series with base 1970 =100

c) Based on series with base 1970 =100

d) Based on series with base 1980-81 =100

e) Based on series with base 1993-94 =100

This picture of industrial buoyancy is not just corroborated but strengthened

by figures on trends in GDP in the manufacturing sector. The GDP in

registered manufacturing not only grew at a faster rate (of 6.9 per

cent) during 1985/86 to 1994/95 than suggested by the IIP, but that

rate of growth rose by a full percentage point to 7.9 per cent during

1994/95 to 2002-03. This brought it close to what was achieved during

the first three Five Year Plans. The unregistered manufacturing sector,

data for which is as expected less reliable, is also reported to have

grown in recent years at rates higher than recorded during any time

in India's post-Independence history. (See

Table 3)

Table

3: Annual Trend Rates of Growth of Manufacturing GDP |

||||

|

Manufacturing |

Registered |

Unregistered

|

||

1950-51

to 64-65 |

6.7 |

8.2 |

5.2

|

|

1965-66

to 79-80 |

6.5 |

7.2 |

5.3

|

|

1965-66

to 74-75 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

3.9

|

|

1975-76

to 84-85 |

5.4 |

6.2 |

4.2

|

|

1985-86

to 94-95 |

6.1 |

6.9 |

4.8

|

|

1994-95

to 02-03 |

6.1 |

7.9 |

5.7

|

|

Differences between trends in GDP in registered manufacturing and in

the IIP are to be expected. While initial estimates of GDP in registered

manufacturing for any year are based on trends in the IIP, these figures

are subsequently revised based on the results of the Annual Survey of

Industries. The latter, because of its methodology and coverage, is

considered a more reliable source of information on the registered manufacturing

sector. Further, it has been argued in the past that the IIP underestimates

the rate of growth of the registered manufacturing sector, which tends

to be higher when computed from value added figures provided by the

ASI with a lag.

However, there is reason to believe that this alone cannot explain recent

differences in the rates of growth of manufacturing GDP and the IIP.

Table 4

provides a comparison between annual rates of growth of registered manufacturing

based on value added figures from the ASI deflated by the GDP deflator

and the rates yielded by the IIP. There are gaps in the series because

data problems have resulted in the information for particular years

being excluded from the time series on principal characteristics of

the factory sector provided by the ASI on its web site. The available

figures suggest that, while it is true that during most years in the

1980s the IIP yielded rates of growth which were lower than warranted

by the ASI figures on value added and value of output, in the 1990s

the reverse seem to be true and with rather wide margins in some years.

Table

4: Annual Growth Rates of Value of Output and Value Added from the ASI and the IIP Rates of Growth of: |

||||

|

VoO

ASI |

NVA

ASI |

IIP

|

||

1982-83 |

11.8 |

9.7 |

1.4

|

|

1983-84 |

1.4 |

12.9 |

5.7

|

|

1984-85 |

6.4 |

-2.2 |

8

|

|

1988-89 |

9.3 |

11.5 |

8.7

|

|

1989-90 |

14.7 |

13.3 |

8.6

|

|

1990-91 |

8.4 |

11.3 |

9

|

|

1991-92 |

-1.3 |

-5 |

-0.8

|

|

1992-93 |

12.2 |

18.4 |

2.2

|

|

1996-97 |

4.8 |

6.9 |

7.3

|

|

1997-98 |

9.8 |

3 |

6.7

|

|

1998-99 |

-10.9 |

-16.9 |

4.4

|

|

1999-2000 |

12 |

4.2 |

7.1

|

|

2000-2001 |

-3 |

-12.9 |

5.3

|

|

2001-2002 |

1.1 |

-2.2 |

2.9

|

|

In

sum, the use of alternate series on output and value added in the registered

manufacturing sector yields results relating to its rate of growth that

do not permit any clear judgement on how Indian industry has been faring.

If the ASI is adopted as a more reliable source, performance appears

to be poor or even pathetic; but if the IIP or GDP figures are taken,

the performance is indeed good. In the event, we are left with no clarity

about the actual performance of the industrial sector. However, the

point to note is that the stagnation and decline of the share of GDP

contributed by the manufacturing sector occurs despite the high rates

of growth in manufacturing GDP reflected in figures from the National

Accounts Statistics.

This implies that answering the question as to whether the stagnation

and decline in manufacturing GDP and the rise in the share of services

in GDP is the sign of a new dynamism associated with a new growth trajectory,

requires assessing more disaggregated data wherever available. Till

such time that such an assessment is made, optimistic generalisations

regarding India's growth performance and prospects have to be treated

with some scepticism.