Themes > Features

08.09..2008

India's Hitech Lag

As

India's government gloats over its US-brokered entry into the world's

nuclear club, it may be sobering to examine the implications of some information

collated in the recently released biennial Science and Engineering Indicators

report of the National Science Foundation (NSF) of the US. Concerned with

the evidence of a growing erosion of US dominance in high technology areas,

these reports have in recent years paid considerable attention to emerging

trends in high technology production and commerce. An important issue

here is the change in the geography of high-technology manufacturing,

with new producers growing rapidly and establishing a presence in global

production and trade. The NSF adopts the OECD’s classification in this

regard and includes the following sectors in the high technology category:

(i) Aerospace, (ii) Pharmaceuticals, (iii) Office and computing machinery,

(iv) Radio, television and communications equipment, and (v) Medical,

precision and optical instruments.

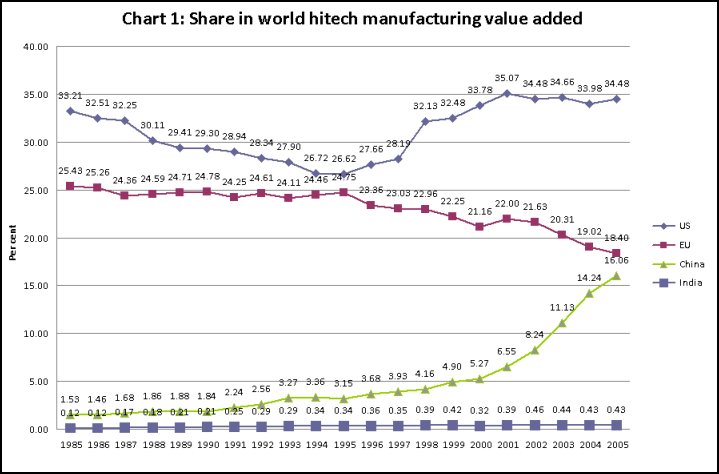

If in the past US attention used to be directed at Japan as an emerging competitor, more recently China and India have been under the scanner. When it comes to hi-tech manufacturing, the focus on China is indeed warranted. But, India, which attracts disproportionate attention because of its success as an exporter of software and IT-enabled services and its recent high rate of growth, has lagged far behind. Thus, if we take the 20-year period from 1985 to 2005, the share of China’s hi-tech manufacturing industries in global value added in the high technology sectors, which rose slowly from 1.53 per cent to 3.15 per cent over the decade 1985 to 1995, subsequently shot up to 16.06 per cent by 2005 (Chart 1). On the other hand, over the 20-year period as a whole India’s share in global high technology manufacturing value added increased from a negligible 0.12 per cent to an almost equivalent and insignificant 0.43 per cent. Interestingly, the US which had seen a substantial decline in its share of global value added in hi-tech areas between 1985 and 1995, managed to reverse this tendency during the second half of the 1990s, largely as a result of an expansion of the radio, television and communications sector and partly because of advances in Office and computing machinery. Thus China’s gain was at the expense of the EU and the rest of the world outside the US.

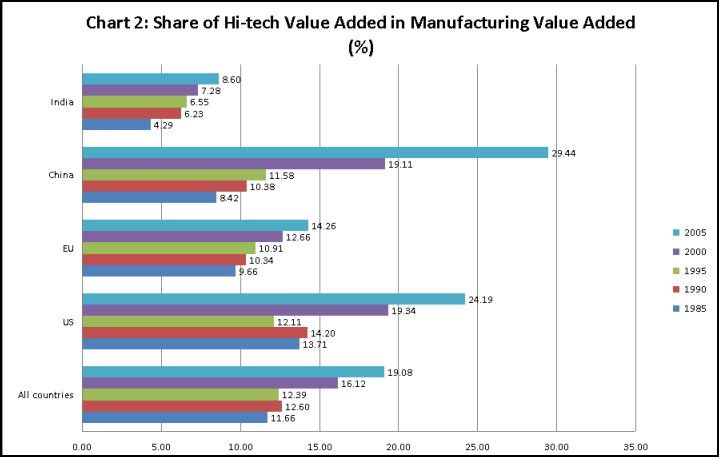

The remarkable performance of China is also reflected in the relative share of the high technology sectors in its manufacturing sector as a whole. Chart2 compares the relative share of value added in the hi-tech sectors in aggregate manufacturing value added in a number of countries. Across the world that share rose from 11.66 per cent in 1985 to 19.08 per cent in 2005. The EU’s performance tracked this trend well, with the relevant share rising in its case from 9.66 to 14.26 per cent. The US performed better, with the share in its case rising from 13.7 to 24.2 per cent. India’s performance, however, is unimpressive. While the share in India doubled from 4.3 to 8.6 per cent, the absolute value of that share was much less than the global average. On the other hand China’s performance was remarkable, with the hi-tech share in its case rising from 8.4 to 29.4 per cent of manufacturing value added over this 20 year period.

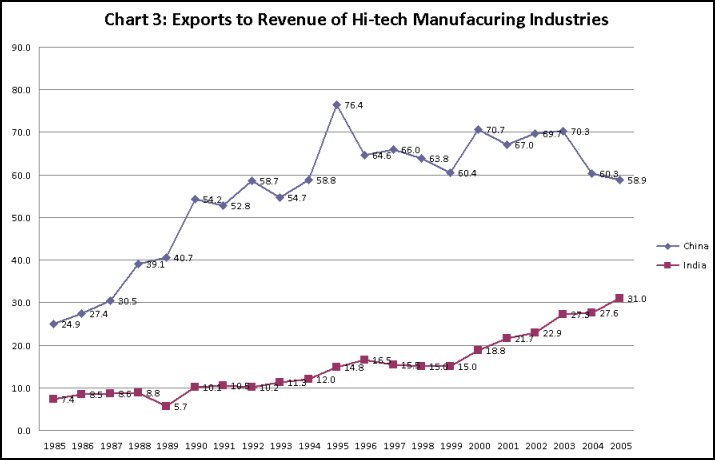

As is to be expected and been noted often, given its per capita income, China's rise in the global league tables for hi-tech manufacturing was the result of a rapid expansion of exports. The ratio of export sales to revenues rose from 25 per cent in 1985 to more than 75 per cent in the mid-1990s, only to moderate later as domestic consumption of high technology products rose along with incomes. By 2005 that ratio had fallen below 60 per cent (Chart 3), because of a rise in domestic consumption and not because of a decline in exports..

If in the past US attention used to be directed at Japan as an emerging competitor, more recently China and India have been under the scanner. When it comes to hi-tech manufacturing, the focus on China is indeed warranted. But, India, which attracts disproportionate attention because of its success as an exporter of software and IT-enabled services and its recent high rate of growth, has lagged far behind. Thus, if we take the 20-year period from 1985 to 2005, the share of China’s hi-tech manufacturing industries in global value added in the high technology sectors, which rose slowly from 1.53 per cent to 3.15 per cent over the decade 1985 to 1995, subsequently shot up to 16.06 per cent by 2005 (Chart 1). On the other hand, over the 20-year period as a whole India’s share in global high technology manufacturing value added increased from a negligible 0.12 per cent to an almost equivalent and insignificant 0.43 per cent. Interestingly, the US which had seen a substantial decline in its share of global value added in hi-tech areas between 1985 and 1995, managed to reverse this tendency during the second half of the 1990s, largely as a result of an expansion of the radio, television and communications sector and partly because of advances in Office and computing machinery. Thus China’s gain was at the expense of the EU and the rest of the world outside the US.

The remarkable performance of China is also reflected in the relative share of the high technology sectors in its manufacturing sector as a whole. Chart2 compares the relative share of value added in the hi-tech sectors in aggregate manufacturing value added in a number of countries. Across the world that share rose from 11.66 per cent in 1985 to 19.08 per cent in 2005. The EU’s performance tracked this trend well, with the relevant share rising in its case from 9.66 to 14.26 per cent. The US performed better, with the share in its case rising from 13.7 to 24.2 per cent. India’s performance, however, is unimpressive. While the share in India doubled from 4.3 to 8.6 per cent, the absolute value of that share was much less than the global average. On the other hand China’s performance was remarkable, with the hi-tech share in its case rising from 8.4 to 29.4 per cent of manufacturing value added over this 20 year period.

As is to be expected and been noted often, given its per capita income, China's rise in the global league tables for hi-tech manufacturing was the result of a rapid expansion of exports. The ratio of export sales to revenues rose from 25 per cent in 1985 to more than 75 per cent in the mid-1990s, only to moderate later as domestic consumption of high technology products rose along with incomes. By 2005 that ratio had fallen below 60 per cent (Chart 3), because of a rise in domestic consumption and not because of a decline in exports..

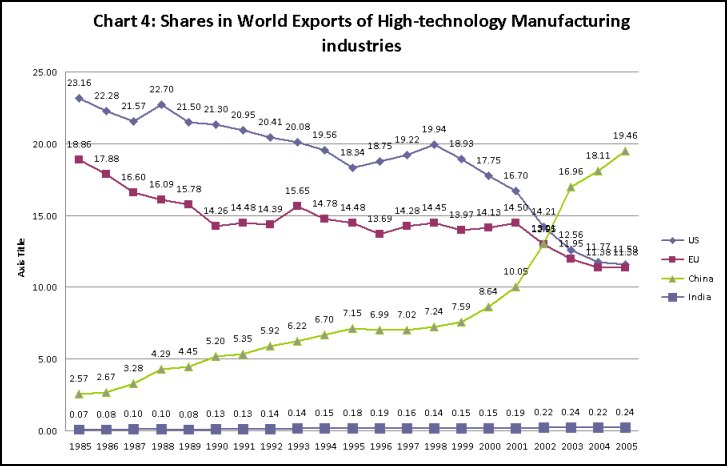

China's

success on the export front has meant that its presence in global hi-tech

trade is even greater than in production, with its share in global hi-tech

manufacturing exports having risen from a little more than 2.5 per cent

in 1985 to close to 20 per cent in 2005 (Chart 4). This rise paralleled

a decline in the shares of both the US and the EU in global trade in

these products. On the other hand, India has been and remains a non-existent

player in global markets for high technology manufacturing.

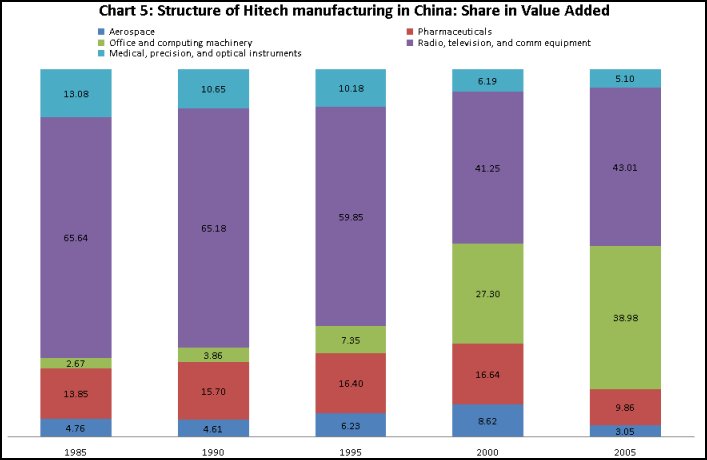

What

is of interest is the structure of the hi-tech manufacturing sectors in

these countries. In the case of China the sector was completely dominated

by the Radio, television and communications equipment sector in the mid-1980s,

when it accounted for almost two-thirds of all hi-tech manufacturing value

added (Chart 5). Since then the production of Office and computing machinery

has been rising rapidly so that by 2005 it accounted for 39 per cent of

hi-tech value added, while that of Radio, television and communications

equipment had fallen to 43 per cent. In sum, information technology hardware

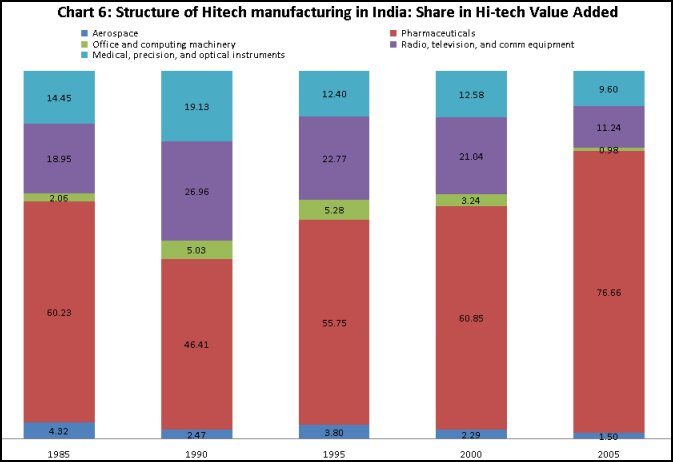

is central to China’s hi-tech success. On the other hand, though India

is considered an information technology power, these two information technology

sectors, which accounted for around 20 per cent of hi-tech value added

in 1985, contributed just about 12 per cent of that value added in 2005

(Chart 6).

Interestingly, the industries that have come to dominate the hi-tech sector in China are the same as those in the US. In 1985, the aerospace industry accounted for close to 50 per cent of value added in hi-tech manufacturing in the US, whereas Office and computing machinery and Radio, television and communications equipment together contributed just 12.25 per cent. By 2005, the share of the latter two sectors had risen to almost 55 per cent. Thus China's trajectory was similar to that of the global leader.

The structure of India's hi-tech sector on other hand was completely different. What is noteworthy is the high share of pharmaceuticals in India’s hi-tech industries. That sector accounted for 60 per cent of value added in 1985 and a massive 77 per cent in 2005. It is well known that India’s pharmaceutical prowess came as a result of a combination of protection for domestic production, control over the operations of foreign firms in India, and, above all, a patenting regime that recognized process patents and not product patents. These were all policies typical of the interventionist, import substituting strategy of development adopted during the first three decades after Independence. The result was the growth of a large and diverse pharmaceutical industry which could ensure the availability of good quality drugs at prices that were among the lowest in the world. The capacities and technological capabilities built up during that time has meant that even though India has given up many of these policies and today recognizes product patents as well, it is in a position to compete globally in many drugs that are off patent or are on the way to being so.

Interestingly, the industries that have come to dominate the hi-tech sector in China are the same as those in the US. In 1985, the aerospace industry accounted for close to 50 per cent of value added in hi-tech manufacturing in the US, whereas Office and computing machinery and Radio, television and communications equipment together contributed just 12.25 per cent. By 2005, the share of the latter two sectors had risen to almost 55 per cent. Thus China's trajectory was similar to that of the global leader.

The structure of India's hi-tech sector on other hand was completely different. What is noteworthy is the high share of pharmaceuticals in India’s hi-tech industries. That sector accounted for 60 per cent of value added in 1985 and a massive 77 per cent in 2005. It is well known that India’s pharmaceutical prowess came as a result of a combination of protection for domestic production, control over the operations of foreign firms in India, and, above all, a patenting regime that recognized process patents and not product patents. These were all policies typical of the interventionist, import substituting strategy of development adopted during the first three decades after Independence. The result was the growth of a large and diverse pharmaceutical industry which could ensure the availability of good quality drugs at prices that were among the lowest in the world. The capacities and technological capabilities built up during that time has meant that even though India has given up many of these policies and today recognizes product patents as well, it is in a position to compete globally in many drugs that are off patent or are on the way to being so.

This

competitiveness is reflected in the growing external orientation of India’s

hi-tech sectors, possibly driven by pharmaceuticals. The ratio of exports

to revenue in the hi-tech industries rose from 7.5 to 15 per cent between

1985 and 1999, and then doubled again to 31 per cent by 2005. The period

between 2000 and 2005 was also one in which the share of pharmaceuticals

in hi-tech manufacturing value added in India rose from 61 to 77 per cent.

This suggests that pharmaceutical production and exports are the most

successful components of India’s otherwise dismal hi-tech manufacturing

performance. Office and computing machinery with its less than 1 per cent

share in 2005 and Radio, television and communications equipment with

its 11 per cent contribution to hi-tech manufacturing value added are

conspicuous by their small presence or near absence. India’s two-decade

long liberalization and "reform" programme has only worsened

its hi-tech lag. This is a feature that must be factored in when attempting

to redress the imbalance.

so.

©

MACROSCAN 2008