Themes > Features

22.09..2010

Ignoring Asset Price Inflation

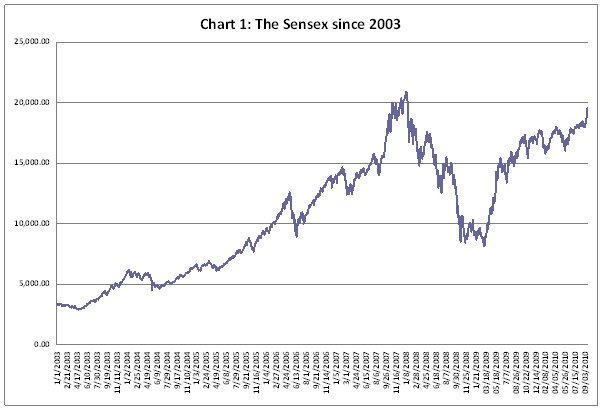

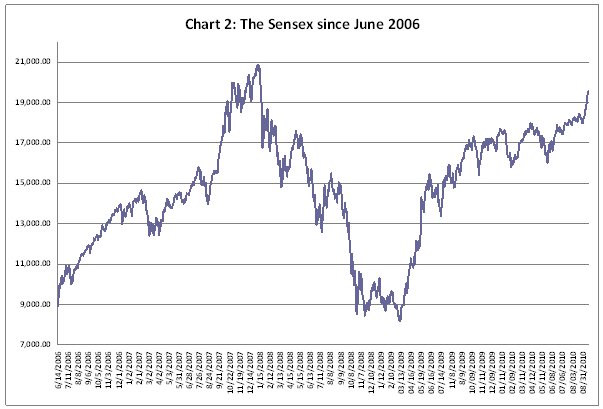

The recent action taken by the Reserve Bank of India to hike repo and reverse repo rates has been interpreted as a shift in focus to inflation control resulting from a combination of comfortable growth figures and disconcerting increases in the prices of goods, especially food articles. What is surprising is that little concern is being expressed and action being taken with regard to the sharp increase in asset prices, especially equity prices. India's stock market recovery over the last year and a half is a bit too remarkable for comfort (Charts 1 and 2). From its March 9, 2009 level of 8,160, the Sensex at closing soared to touch 19,594 on September 17, 2010. This is not far short of the 20,870 peak the index closed at on September 1, 2008. This steep increase the index has registered in recent months occurs when the after effects of the global crisis are still being felt in various parts of the world where the recovery has been halting and unemployment still rampant.

This rapid rise in stock prices cannot be justified by movements in corporate sales and profits. In fact, the price earnings ratio of many Sensex companies now stands at levels which many market observers see as unsustainable, resulting in recommendations that investors should book profits and hold cash till the market corrects itself. Those comfortable with the market's rise would of course argue that investors, expecting a robust recovery, are implicitly factoring in future earnings trends, rather than relying on earnings figures that are the legacy of a recession. However, there are obvious reasons for caution. In the coming months the once-for-all component in the stimulus that the Sixth Pay Commission's recommendations provided would wane. And once the windfall gains from privatisation and spectrum sales are inadequate to reduce the deficit on the government's budget, a cutback of government expenditure is likely. Finally, exports are still doing badly and the global recovery is widely expected to be gradual and limited. That would limit the stimulus provided by India's foreign trade. Given these circumstances, excessive optimism with regard to corporate earnings is hardly justified. The change in perception from one in which India was a country that weathered the crisis well to one that sees India as set to boom once again is not grounded in fundamentals of any kind.

This

implies that the current bull run can be explained only as being the

result of a speculative surge that recreates the very conditions that

led to the collapse of the Sensex from its close to 21,000 peak of around

a year ago. This surge appears to have followed a two stage process.

In the first, investors who had held back or withdrawn from the market

during the slump appear to have seen India as a good bet once expectations

of a global recovery had set in. This triggered a flow of capital that

set the Sensex rising. Second, given the search for investment avenues

in a world once again awash with liquidity, this initial spurt in the

index appears to have attracted more capital, triggering the current

speculative boom in the market.

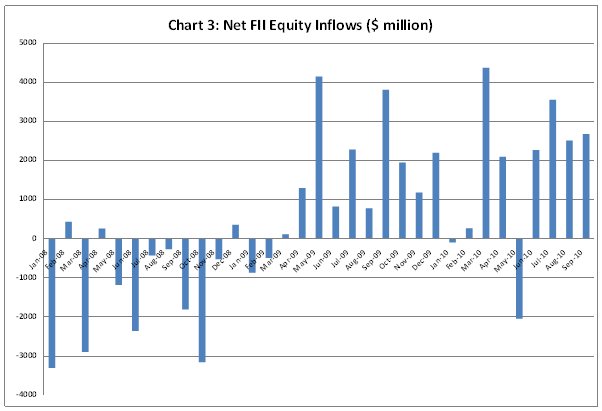

While these are possible proximate explanations of the transition from

slump to boom, they in turn need explaining. In doing so, we have to

take account of the fact that, as in the past, foreign investors have

dominated stock market transactions and had an important role in triggering

the current stock market boom. As compared to the net sales of equity

to the tune of $14.84 billion by foreign institutional investors during

crisis year 2008, they had made net purchases of equity worth $17.23

billion during 2009. During 2010 that figure had touched $15.62 billion

by the middle of September. In fact figures on FII investment do not

tell the whole story on the effects of foreign investors on equity prices.

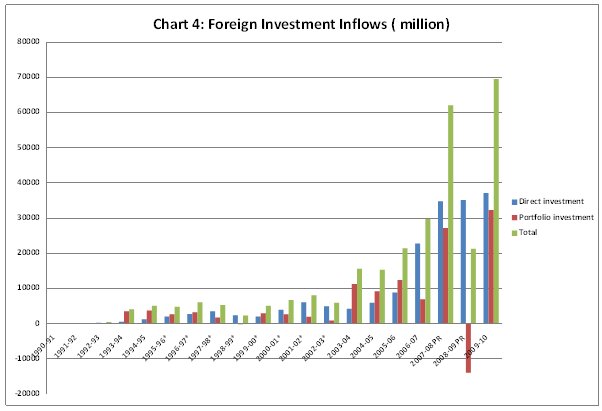

Figures from the RBI indicate that not only did foreign portfolio investment,

which fell from $27.3 billion in 2007-08 to a negative $13.86 billion

in 2008-09, bounce back to $32.38 billion in 2009-10, but foreign direct

investment has risen consistently from $34.83 billion to $35.18 billion

and $37.18 billion over these years. In the event total foreign investment

was close to a record $70 billion in 2009-10. Since any investment equal

to or exceeding 10 per cent of stock in a company by a single investor

is defined as direct investment, a significant amount of purely private

investment gets treated as direct investment in the figures. Thus, speculative

financial investments could have been significantly higher in recent

months.

It is not surprising that foreign institutional investors have returned to the market. They need to make investments and profits to recoup losses suffered during the financial meltdown. And they have been helped in that effort by the large volumes of credit provided at extremely low interest rates by governments and central banks in the developed countries seeking to bail out fragile and failing financial firms. The credit crunch at the beginning of the crisis gave way to an environment awash with liquidity as governments and central bankers pumped money into the system at near-zero interest rates. Financial firms have chosen to borrow and invest this money in markets where returns are promising so as to quickly turn losses into profit. Some was reinvested in government bonds in the developed countries, since governments were lending at rates lower than those at which they were borrowing. Some was invested in commodities markets, leading to a revival in some of those markets, especially oil. And some returned to the stock and bond markets, including those in the so-called emerging markets like India. Many of these bets, such as investments in government bonds, were completely safe. Others such as investments in commodities and equity were risky. But the very fact that money was rushing into these markets meant that prices would rise once again and ensure profits. In the event, bets made by financial firms have come good, and most of them have begun declaring respectable profits and recording healthy stock market valuations.

It

is to be expected that a country like India would receive a part of

these new investments aimed at delivering profits to private players

but financed at one remove by central banks and governments. In their

case the ''carry trade'' appears extremely profitable. Not surprisingly,

India has received more than a fair share of these investments. One

way to explain this would be to recognise the fact that India fared

better during the recession period than many other developing counties

and was therefore a preferred hedge for investors seeking investment

destinations. The other reason is the expectation fuelled by the return

of the UPA to government, this time with a majority in Parliament and

the repeated statements by its ministers that they intend to push ahead

with the ever-unfinished agenda of economic liberalisation and ''reform''.

The UPA II government has, for example, made clear that disinvestment

of equity in or privatisation of major public sector units is on the

cards. That caps on foreign direct investment in a wide range of industries

including insurance are to be relaxed. That public-private partnerships

(in which the government absorbs the losses and the private sector skims

the profits) are to be encouraged in infrastructural projects, with

government lending to or guaranteeing private borrowing to finance private

investments. That the tenure of tax concessions given to STPI units

and units in SEZs are to be extended. And that corporate tax rates are

likely to be reduced and capital gains taxes perhaps abolished.

All of this generates expectations that there are likely to be easy

opportunities for profit delivered by an investor-friendly government

in the near future, including for those who seek out these opportunities

only to transfer them for profit soon thereafter. These opportunities,

moreover, are not seen as dependent on a robust revival of growth, though

some expect them to strengthen the recovery. In sum, whether intended

or not, the signals emanating from the highest economic policy making

quarters have helped talk up the Indian market, allowing equity prices

to race ahead of earnings and fundamentals. Once the speculative surge

began, triggered by the inflow of large volumes of footloose global

capital, Indian investors joined the game financed very often by the

liquidity being pumped into the system by the Indian central bank. The

net result is the current speculative boom that seems as much a bubble

as the one that burst not so long ago. What is more, that bubble is

being expended by the strengthening of the rupee that the capital inflows

result in, which promises even higher returns on carry trade investments.

There are three conclusions that flow from this sequence of events.

The first is that using liquidity injection and credit expansion as

the principal instrument to combat a downturn or recession amounts to

creating a new bubble to replace the one that went bust. The problem

is that while the error was made largely in the developed countries,

where the so-called stimulus involved injecting liquidity and cheap

credit into the system, the effects are felt globally including in emerging

markets like India. The second is that so long as the rate of inflation

in the prices of goods is in the comfort zone, central bankers stick

to an easy money policy even if the evidence indicates that such policy

is leading to unsustainable asset price inflation. It was this practice

that led to the financial collapse triggered by the sub-prime mortgage

crisis in the US. Third, that governments in emerging markets like India

have not learnt the lesson that when a global expansion in liquidity

leads to a capital inflow surge into the country it does more harm than

good, warranting controls on the excessive inflow of such capital. Rather,

goaded by financial interests and an interested media, the government

treats the boom as a sign of economic good health rather than a sign

of morbidity, and plans to liberalise capital controls even more. In

the event, we seem to have engineered another speculative surge. The

crisis, clearly, has not taught most policy makers any lessons.

©

MACROSCAN 2010