Things seem to be improving in education in developing

countries, at least as far as enrolment is concerned.

Across the world, literacy rates have gone up, school

enrolment rates are rising and dropout rates are falling.

Much of the improvement has taken place in the regions

that most needed it, in relatively low income countries

that previously had very low enrolment ratios. Improvements

in educational outcomes have been particularly marked

for girls and young women, so gender gaps are falling.

In some regions, gender gaps have even been reversed,

even in tertiary education which was traditionally

the hardest gap to bridge.

This is clearly good news, even if critics can point

out that in several parts of the world these improvements

are still nowhere near fast enough. And of course

the bare fact of enrolment tells us very little about

the quality of education and its relevance for both

those being educated and for the society. Even so,

increasing enrolment is an important first step.

What is particularly interesting in several developing

regions, including the most populous parts of the

world, is that there has also been significant increase

in tertiary education. Once again, this is good news.

But it does have implications for the future that

are still inadequately analysed.

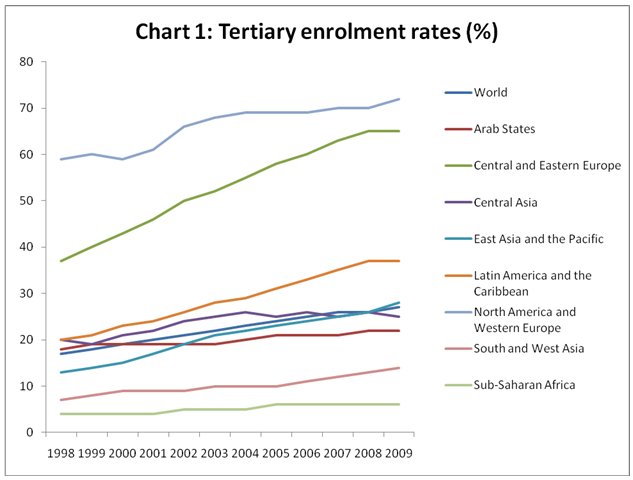

UNESCO data on enrolment in education provide some

relevant indicators. Chart 1 shows the enrolments

in tertiary education by region. The first point to

note is that while globally tertiary enrolment rates

have been rising, regional differences still remain

dramatic. These spatial variations are possibly even

more marked within the developing world than globally.

Thus, tertiary enrolment rates have been rising fairly

rapidly in Latin America and the Caribbean as well

as East Asia and the Pacific, but much more slowly

in the Arab States and in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

Despite

the recent increases in such enrolment in east Asia

(and to a lesser extent South Asia), higher education

enrolment in these regions still remains at less than

half the rates achieved in Europe and North America,

and also still well below other developing regions

like Latin America. What that in turn suggests is

that - especially in the more rapidly growing regions

- higher education enrolment rates will increase even

more sharply in the near future.

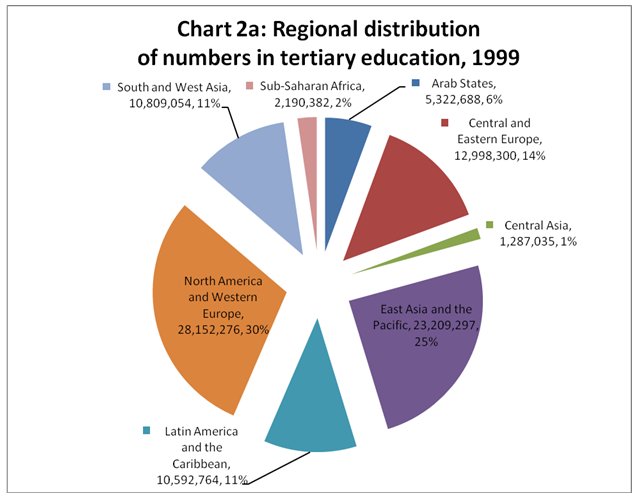

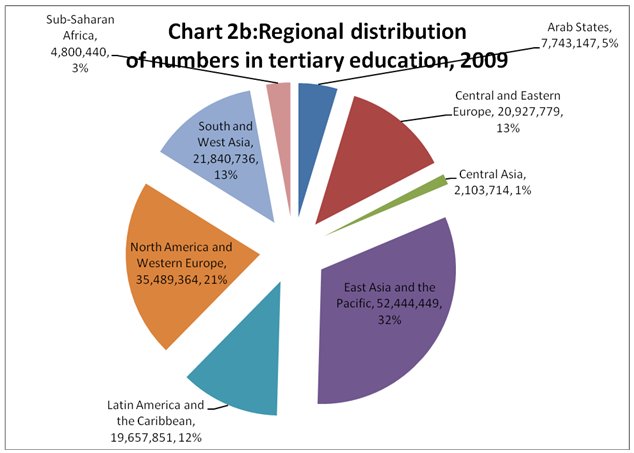

This is significant simply because these are the regions

with very large populations and especially with large

(and mostly growing) numbers of youth. This in turn

will affect the regional distribution of those in

higher education quite significantly. This has already

happened to some extent over the last decade, as Charts

2a and 2b indicate. In 1999, North America and Western

Europe accounted for nearly one-third of the numbers

of those engaged in tertiary education; by 2009 the

proportion had fallen to just above one-fifth. Meanwhile

the share of East Asia increased from one quarter

to nearly one-third.

Chart

2a >>

Click

to Enlarge

Chart

2b >>

Click

to Enlarge

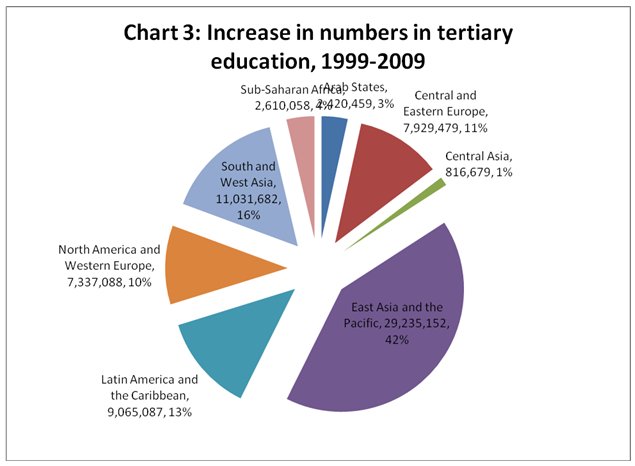

This tendency is confirmed by looking at the increases

in enrolment numbers in Chart 3. In the decade until

2009 the total number of those enrolled in tertiary

education across the world increased by more than

70 million, of whom nearly 60 per cent came from Asia.

42 per cent of the increase came only from East Asia

and the Pacific (driven by significant increases in

China). The other regions with demographic structures

tilted towards the young are South Asia and West Asia

- together they accounted for only 16 per cent of

the increased enrolment in the past decade, but this

is likely to be greater in the coming period, given

increases in secondary education in these regions.

Since Asia and sub-Saharan Africa continue to have

much lower average tertiary enrolment rates (averaging

10 to 20 per cent compared to more than 60 per cent

in the advanced countries), this proportion is likely

to increase even further in the near future. So the

bulk of new entrants into higher education will come

from these regions in the coming decade.

Chart

3 >>

Click

to Enlarge

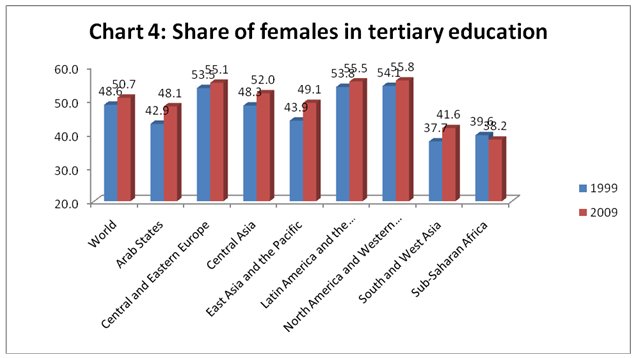

It is noteworthy that the number of women in tertiary

education has increased at a much faster rate than

for men, as shown in Chart 4. Globally, women now

outnumber men in tertiary education! In some regions

(like North America, Western Europe, Latin America

and Eastern Europe) the ratio is significantly above

half. This too is a process of great significance,

because it is likely to bring in its wake all sorts

of social and economic changes - and hopefully a much

greater degree of gender equality in other spheres

of life as well.

Chart

4 >>

Click

to Enlarge

The increase in tertiary education in the developing

world is clearly a positive sign - and obviously there

is much scope for substantially more such increase

in the coming years. But, like all positive changes,

it also brings forth challenges, and many of these

are still not recognized in full. The most obvious

challenge is that of ensuring enough productive employment

to meet the expectations of these new graduates.

This issue of ensuring jobs for the young are going

through more levels of education than the previous

generation has several interrelated aspects. The first

is that of sheer quantity of available jobs. Even

during the phase of global boom, the most dynamic

economies in the world were simply not creating enough

paid employment to meet the needs of those willing

to supply their labour. In some countries this reflected

in rising rates of open unemployment, especially among

the youth; in other countries with poorly developed

social protection and unemployment benefits, disguised

unemployment was more the norm. But this was during

the boom - obviously the Great Recession and subsequent

continuing uncertainty in global markets have made

things a lot worse. So in most economies, there are

simply not enough jobs being created, even for those

who have received higher levels of education.

The second aspect is that of quality, of matching

education and skills with the available jobs, or what

is often described as the ''employability'' of the

labour force. This problem of skills mismatch is a

problem even in growing economies, which face severe

labour shortages for some kinds of workers and massive

oversupply in others. Often this is not in spite of,

but because of, market forces, because markets and

higher educational institutions tend to respond with

lags to the demands of employers for particular skills,

and then to oversupply certain skills.

This can have troubling social implications. Simply

because of the shortage of higher level jobs, many

young people are forced to take jobs that require

less skills and training than they have actually received,

and are of lower grade than their own expectations

of their employability. This in turn can create resentment

and other forms of alienation that get expressed in

all sorts of ways.

The third aspect - and one that we all ignore at our

peril - is related to the second, but reflects a slightly

different process. The recent increase in tertiary

enrolment across the world is certainly to be welcomed,

but it should be noted that a significant part of

that has been in private institutions with much higher

user fees. As public investment in education has simply

not kept pace with the growing demand for it, there

has been in many societies, a mushrooming of private

institutions - many of whom are designed to cater

to the demand for supposedly more ''marketable'' skills

such as in technology, IT and management.

This is especially true in developing countries, where

private institutions charging very high fees have

in some cases come to dominate higher education. In

India, for example, around two-thirds of such enrolment

is now estimated to be in private colleges and universities

and similar institutes. Even in countries where public

education still dominates, there are moves to increase

fees.

This creates another complication around the issue

of employability. Many students, including those coming

from relatively poor families, have invested a great

deal of their own and their familiesí resources in

order to acquire an education that comes with the

promise of a better life. In the developing world,

this hunger for education is strongly associated with

the hope of upward mobility, leading families to sell

assets like land and go into debt in the hope of recouping

these investments when the student graduates and gets

a well-paying job.

But such jobs, as noted earlier, are increasingly

scarce. And so these many millions of young people

who will emerge with higher degrees, often achieved

not just with a lot of effort but a lot of financial

resources, are likely to find it even harder to find

the jobs that they were led to expect. This does not

augur well for social and political stability. Policy

makers across the world, and particularly in developing

countries with a demographically youthful society,

need to be much more conscious of this challenge than

they seem to be at present.

*

This article was originally published in the Business

Line on September 6, 2011.