Themes > Features

5.09.2012

Financial Convergence in Asia*

The

discussion on the direction that financial regulation should take in

Asia inevitably turns to the diversity in regulation across countries

in its search for an appropriate combination of policies and measures.

The presumption here is that the rich diversity in the region offers

a menu from which a combination of institutions and instruments and

a corresponding regulatory framework can be put together. The case for

focusing on Asian policy has been strengthened by the resilience displayed

by Asian countries during the global financial crisis of 2007-08 and

after, despite their substantial integration with the global financial

system.

While there is a case for such an effort to learn from diversity, there

is also much evidence that monetary, fiscal and financial policies and

the associated macroeconomic scenario have been converging across Asian

countries since the onset of financial liberalisation and more so since

the Southeast Asian financial crisis of 1997. The ostensible role of

the 1997 crisis in influencing macroeconomic policy in these countries

has been much discussed after the global crisis. The 1997 experience,

it is argued, persuaded these countries to maintain a high volume of

foreign exchange reserves to deal with any volatility in cross-border

capital flows and excessive fluctuations in their currencies, leading

to a situation of capital flows from South to North, rather than North

to South as under the Bretton Woods system.

Among the many commonalities in the evolution of financial structures

in the region, there are a few that are particularly striking. The first

is, of course, the evidence of the growing integration of these economies

with the international financial system, which is reflected in a rising

ratio of net capital flows to GDP in almost all of these countries after

2003 and an increase in foreign bank claims on these countries in recent

years (Table 1). This is because, even while reserves accumulate, these

countries continue with open door policies that encourage cross-border

inflows of capital. The resulting outcome is relevant not merely because

it amounts to a reversal of the trend seen in the immediate post-1997

years, when as a result of the crisis the access of many countries to

foreign finance appeared to be falling. Clearly, countries now are able

to attract capital and are also unable to avoid or are willing to address

the dangers (in the form of balance of payments and/or currency crises)

of dependence on volatile cross-border flows.

From a policy point of view, the increase in the presence of foreign

capital has necessitated changes in the regulatory framework governing

finance in these countries. Governments in the region have adopted more

liberal rules with regard to the functioning of different kinds of markets

and institutions, provided greater space for new instruments such as

derivatives, and shown a willingness to shift to globally accepted rules

for regulation. One consequence has been a rapid shift to a Basel-type

regulatory framework for the banking system. In fact, countries in the

region are on average more eager to move on to Basel III than seems

to be the case even in the developed countries where the crisis that

forced the transition from Basel II to III occurred. The message seems

to be that if countries choose to adopt a macroeconomic policy framework

that emphasises the need to attract large volumes of foreign capital,

reform of the regulatory structure governing finance in a common, globally

dictated direction seems to be a prerequisite.

Table

1: International bank claims, consolidated (Bn USD) |

|||||

Europe

|

|||||

2005-Q4 |

2007-Q1 |

2009-Q1 |

2012-Q1 |

||

China |

44.3 |

90.0 |

98.7 |

261.0 |

|

Hong

Kong |

192.6 |

223.8 |

240.5 |

359.9 |

|

Indonesia |

12.6 |

19.5 |

22.7 |

36.1 |

|

India |

49.0 |

78.6 |

112.1 |

150.6 |

|

South

Korea |

120.7 |

165.5 |

159.5 |

161.4 |

|

Malaysia |

32.0 |

43.7 |

39.9 |

57.0 |

|

Singapore |

70.6 |

101.0 |

120.3 |

179.8 |

|

Thailand |

11.5 |

17.5 |

15.5 |

21.8 |

|

Japan

|

|||||

2005-Q4 |

2007-Q1 |

2009-Q1 |

2012-Q1 |

||

China |

13.1 |

18.6 |

24.3 |

52.9 |

|

Hong

Kong |

19.2 |

23.9 |

28.6 |

50.8 |

|

Indonesia |

3.8 |

6.0 |

7.2 |

15.5 |

|

India |

5.9 |

8.4 |

11.7 |

25.2 |

|

South

Korea |

15.7 |

21.6 |

25.6 |

48.0 |

|

Malaysia |

5.8 |

6.3 |

9.1 |

13.7 |

|

Singapore |

11.8 |

16.9 |

26.0 |

40.8 |

|

Thailand |

9.8 |

12.6 |

14.5 |

35.1 |

|

US |

|||||

2005-Q4 |

2007-Q1 |

2009-Q1 |

2012-Q1 |

||

China |

9.8 |

21.7 |

51.6 |

76.9 |

|

Hong

Kong |

22.6 |

21.3 |

29.2 |

47.6 |

|

Indonesia |

2.8 |

4.9 |

5.9 |

12.7 |

|

India |

20.5 |

36.4 |

40.5 |

72.0 |

|

South

Korea |

54.6 |

71.5 |

72.4 |

94.7 |

|

Malaysia |

9.9 |

13.1 |

13.1 |

20.2 |

|

Singapore |

20.5 |

24.8 |

30.6 |

64.0 |

|

Thailand |

3.5 |

6.1 |

6.6 |

12.3 |

|

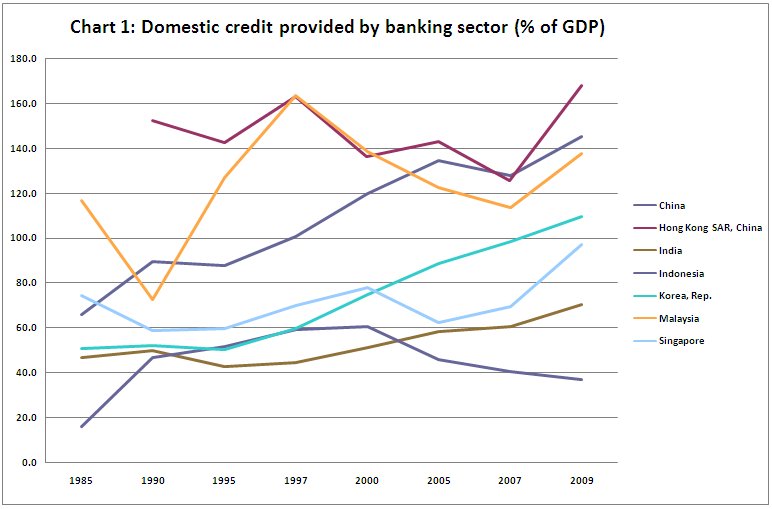

A second element of commonality in these countries appears to be a growth process associated with a large expansion of bank credit. Bank credit growth has overshot GDP growth in almost all countries, resulting in a sharp increase in the bank credit to GDP ratio (Chart 1). As is well known, banks, given their dependence on deposits for their capital, would prefer to avoid exposure to illiquid assets with lower resale value such as industrial capital equipment, because it would expose them to the risks associated with liquidity mismatches. The net result has been a substantial increase in credit to the household sector or in retail credit/personal loans for housing, for purchases of automobiles and durables and for consumption. According to estimates relating to the middle of the last decade: ''Of the domestic credit that banks have extended to private borrowers, a growing share has gone to consumers. In 2004, consumer lending accounted for 53 per cent of total bank lending in Malaysia, 49 per cent in Korea, 30 per cent in Indonesia, 17 per cent in Thailand, 15 per cent in China, and 10 per cent in the Philippines.'' Even in countries where the estimates suggest that retail lending is low, such as China and Thailand, this is because banks that do not lend directly to the household sector often do so indirectly. They provide credit to a second tier of intermediaries, often in the informal financial sector, which in turn lend to households. While a large proportion of these loans is for housing, other loans such as for purchases of automobiles or to finance credit-card receivables have also increased considerably. The focus seems to be on lending short term or against assets considered more liquid.

The third common feature in the evolution of Asian financial structures

is the kind of financial diversification visible in these economies.

Given the huge increase in banks' claims on other sectors of the economy,

the financial transformation of Asia has not been accompanied by a reduction

in the importance of banks in the financial sector. Rather banks still

account for a substantial share of assets resting in the financial sector.

Yet the evidence of a growing role for stock and bond markets and insurance

companies, mutual funds and pension funds is overwhelming. But the nature

of this presence needs examination.

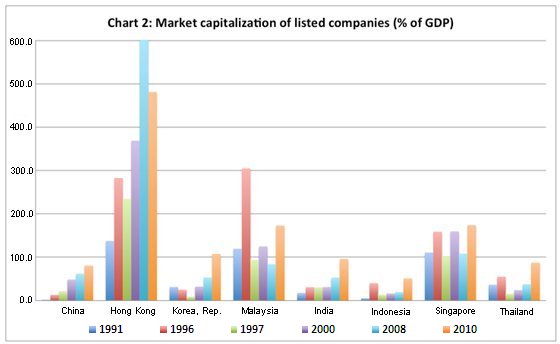

Consider, to start with, the stock markets in these countries. An index

like the ratio of market capitalization to GDP (Chart 2), to a much

greater extent than the number of listed companies or the volume of

trading, points to a huge increase in the size of these markets. However,

much of this is a result of the inflation in stock prices that has resulted

from trading in the secondary market. The IPO market (or the role of

the stock market as a source of capital to finance corporate investment)

is still limited and highly volatile in terms of volumes mobilised.

Asset price inflation occurs partly because of the inflow of foreign

capital and domestic surpluses into the secondary market which is both

narrow (in terms of the number of companies whose shares are listed

and actively traded) and shallow (in terms of the number of shares of

these companies available for trading after taking account of the holdings

of promoters and long-term investors). In sum, though the stock market

seems present and growing in size and visibility, it is as yet not an

important agent from the point of view of making finance a supply-side

spur to corporate investment.

Interestingly, the development of the bond market too remains limited

and highly uneven across the region (Table 2). It is only in South Korea

that the corporate local currency bond market exceeds the government

bond market in size. Moreover, even where bond markets are developed,

government securities seem to account for a significant share of all

securities issued in the domestic market. There are differences in the

relative shares of the corporate bond market in the incremental growth

of these markets; but just as banking dominates the financial sector,

government securities still dominate bond markets in most contexts.

This is of significance given the trend towards reining in government

borrowing not just from central banks but also from the open market.

Unless counterbalanced by the growth of the corporate bond market, this

could see some shrinking in the relative importance of bond markets

in these countries.

As for other segments of the financial sector such as insurance companies,

pension funds and mutual funds, growth is driven largely by three factors.

One is the lack in many of these countries of an extensive system of

social security, necessitating investment in insurance or financial

assets to provide for contingencies and retirement. The second is the

growing privatisation of parts of even the limited insurance and pension

system, encouraging entry of a new set of private institutions, including

foreign ones. And the third is the lack of adequate savings options

for sections of the middle class emerging from the process of rising

per capita incomes. They then turn to investments in mutual funds as

a means to invest small sums in equity or debt markets. However, the

resources mobilised in these sectors too are not percolating into the

productive sectors.

Table

2: Size of LCY Bond Market in % GDP (Local Sources) |

|||||||||||||||

Ratio

of government local currency bonds to GDP (%) |

Ratio

of corporate local currency bonds in GDP (%) |

||||||||||||||

CN |

HK |

ID |

KR |

MY |

SG |

TH |

CN |

HK |

ID |

KR |

MY |

SG |

TH |

||

Dec-95 |

5.3 |

12.6 |

15 |

6.9 |

12.6 |

0 |

8.9 |

0.5 |

|||||||

Dec-00 |

16.6 |

8.2 |

35.4 |

25.7 |

38 |

26.6 |

22.8 |

0.3 |

27.6 |

1.4 |

48.8 |

35.2 |

20.9 |

4.5 |

|

Dec-05 |

36.4 |

9.2 |

17.1 |

45.9 |

42.6 |

37.4 |

37.6 |

2.8 |

38.8 |

2.1 |

42.1 |

31.7 |

28.8 |

8.1 |

|

Dec-11 |

33.9 |

37.1 |

11.4 |

47.5 |

56.6 |

47 |

54.5 |

11.4 |

31.9 |

2 |

67 |

38 |

28.2 |

13 |

|

Finally, a fourth common feature, but one that is uneven in evolution across countries is the increase in securitisation and the growth of derivatives markets. Given the substantial increase in bank credit and its role in financing a segmented and diverse retail market, banks would want to transfer risk for a fee. To do that they need to create low risk securities by combining assets from different markets, geographies and income groups. Once the securitisation process begins, the distance to complex derivatives is short, and there is a replication of the market for complex and opaque assets in Asian developing countries as well.

The implications of these features of the evolution of Asian finance need emphasising. The functional school of finance and the votaries of financial liberalisation it has spawned make a case for financial diversification, financial deepening (with a higher ratio of financial assets to GDP), and increased financial intermediation on the grounds that it facilitates the process of intermediation between savers and investors and does so in the most ''efficient'' way possible. This suggests that finance is an instrument facilitating investment from the supply side by mobilising capital and channelling it to the high return projects that might otherwise be deprived of needed support.

However, as noted above, the recent Asian experience would suggest that financial proliferation largely facilitates new lines of business in financial services and affects the real economy more from the demand side through the debt-financed household expenditure it promotes. One consequence is that excessive exposure to retail markets becomes a source of fragility in these countries just as it did in the developed countries.

As compared to this it was during the years of regulation and so-called ''financial repression'' with its development banks, directed credit programmes and differential interest rates, that efforts were made to channel finance into productive activities, including in sectors like agriculture that would have been otherwise deprived of credit at reasonable interest rates. During those years finance was important as a supply side facilitator of investment, but the proliferation of financial markets, institutions and instruments was limited. That did not, however, limit but rather helped the financing of the real economy.

* This article was originally published in the Business Line on 3 September 2012.

©

MACROSCAN 2012