In

recent years, well-to-do Indians have been sending

foreign exchange abroad to acquire assets either directly

or indirectly, through their relatives resident in

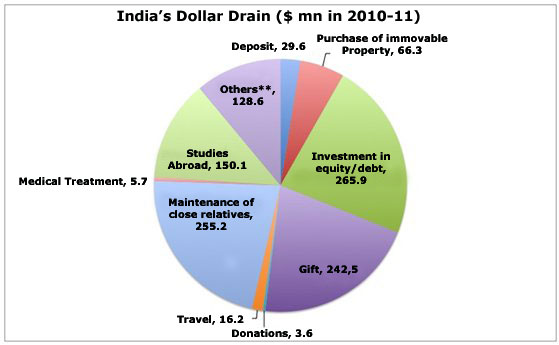

foreign locations. In 2010-11, for example, Indian

residents invested $266 million (around Rs. 1,300

crore) in equity abroad and bought immovable property

worth $66 million. That aside they gifted money to

or financed the expenditures of kith and kin abroad

to the tune of around $500 million (Rs 2,500 crore)

in that year. Add to this, remittances abroad for

purposes such as studies, travel and medical treatment,

and what is termed ''outward remittances by resident

Indians'' by the Reserve Bank of India totalled $1.2

billion in 2010-11.

Chart

1 >> (Click

to Enlarge)

That might seem small relative to the magnitude of

India's trade and of capital inflows into the country.

But it is a figure that is rising. Estimated at $9.6

million in 2004-05 and $72.8 million in 2006-07, the

figure jumped to $440.5 million in 20007-08 and has

almost tripled itself by 2010-11.

The spurt in capital outflow was, of course, policy

induced. In February 2004 the government announced

a new Liberalised Remittance Scheme for Indian residents,

marking a small but significant push in the direction

of full rupee convertibility. Under the Scheme, resident

individuals were permitted to convert rupees into

foreign exchange to acquire and hold immovable property

or shares or debt instruments or any other of a set

of specified assets outside India, without prior approval

of the Reserve Bank. They were also permitted for

this purpose to open, maintain and hold foreign currency

accounts with banks outside India for carrying out

transactions permitted under the Scheme.

The scheme seems to have been motivated by the need

to increase demand for foreign exchange in the country,

to exhaust a part of the large flows of foreign capital

that were finding their way to India. But when the

scheme was launched, the ceiling on transfer for capital

account purposes was set at $25,000 per person per

calendar year. Finding the flow inadequate for its

purposes the government hiked the ceiling to US $

50,000 in December 2006 (per year) and further to

US $ 1,00,000 (per year) in May 2007. At that point,

remittances towards gift and donation by a resident

individual as well as investment in overseas companies

were subsumed under the scheme and included in the

ceiling. This too proved insufficient and the ceiling

was raised just four months later in September 2007

to $200,000 per person per year. This implies that

a family of five would be permitted to transfer a

total sum of a million dollars a year under the heads

of investments and gift. This is what has resulted

in the remittance trickle out of the country turning

into a significant drain.

Note that 2007-08 was the year when India was the

target of a foreign (fixed and portfolio) investment

surge. Investment inflows rose from a historical peak

of $29.8 billion dollars in 2006-07 to $62.1 billion

dollars in 2007-08. Along with this surge in capital

inflows, foreign currency assets with the Reserve

Bank of India rose from $192 billion on March 31,

2007 to $299 billion on March 31, 2008. Very clearly

the capital inflow surge was forcing the central bank

to buy up the surplus foreign exchange in the country,

to prevent excessive appreciation of the currency,

since that was eroding the competitiveness of India's

exports. The result was that the RBI was burdened

with excess foreign reserves, and was therefore finding

it difficult to control money supply. Managing monetary

policy and the exchange rate at the same time was

proving a problem. In response, the government decided

to stimulate demand for foreign exchange from the

private sector. To that end it hiked the right of

the well-heeled Indian to purchase foreign currency

in India to acquire assets abroad. India's rich responded

leading to the sharp increase in remittances to finance

the acquisition of such assets.

Significantly, the four heads under which remittance

outflows have increased the most between 2006-07 and

2010-11 are: investment in equity/debt (from $21 million

to $266 million); gifts to close relatives (from $7

million to $243 million); maintenance of close relatives

(from negligible amounts to $255 million); and, purchase

of immovable property (from $9 million to $66 million).

Clearly there is a decision being made here to sell

domestic assets, convert domestic currency into foreign

exchange and hold assets abroad.

Fortunately for India, the global crisis of 2008 curtailed

and then moderated capital inflows and stabilised

India's foreign currency assets at lower levels. If

not the liberalisation in policy may have continued

and the ceiling on outflows relaxed even further.

As a result the outflow surge may have been greater.

This emerging trend could change the perception of

what constitutes a foreign remittance in the vocabulary

of an Indian. As of now, when you speak of remittances

in India, the image conjured is one of the myriad

Indians, skilled and unskilled, working as temporary

migrants and sending home a part of their earnings.

Private transfers, consisting largely of such remittances

amounted to $53 billion in 2010-11. That was more

or less exactly equal to the inflows on account of

exports of software services in that year. Given the

hype surrounding the software industry, it is clear

that the short-run Indian migrant is clearly an unsung

hero in recent Indian development.

Compared to such figures the $1.2 billion of outward

remittances being discussed here is still miniscule.

But the rising Indian appetite to invest abroad could

prove a problem if economic uncertainty increases,

especially uncertainty with regard to the rupee were

to rise. Such uncertainty could trigger capital flight

in a liberalised environment. Even if a tenth of the

top one per cent of Indians enter the category of

households that can mobilise the equivalent of $200,000

a year, the sum involved would be $240 billion. That

is by no means small, even relative to India's $260

billion reserve of foreign currency assets, since

much of that reserve is built with capital that has

the right to exit the country. India's elite may well

choose to economically secede from the country, precipitating

a crisis in the balance of payments.

*

This article was originally published in the Hindu

on 7th April 2012 and is available at

http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/Econo

my_Watch/article3290980.ece