There

are important changes taking place in labour markets

in India. The results of the latest large round of

the National Sample Survey Organisation, which took

place in 2004-05, have just been released. They reveal

some significant changes in the employment patterns

and conditions of work in India over the first half

of this decade.

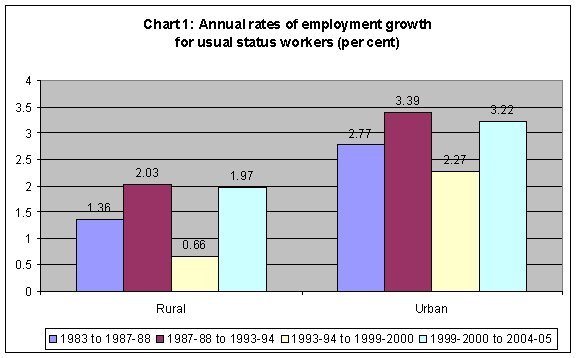

First,

aggregate employment has been growing again. The first

important change from the previous period relates

to aggregate employment growth itself. The late 1990s

was a period of sharp deceleration of aggregate employment

generation, which fell to the lowest rate recorded

since such data began being collected in the 1950s.

However, the most recent period indicates a recovery,

as shown in Chart 1.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

While aggregate employment growth

(calculated at compound annual rates) in both rural

and urban India was still slightly below the rates

recorded in the period 1987-88 to 1993-94, it clearly

recovered sharply from the deceleration of the earlier

period. The recovery was most marked in rural areas,

where the earlier slowdown had been sharper.

At

the same time, however, unemployment rates have also

been increasing, and are now the highest ever recorded.

Unemployment measured by current daily status, which

describes the pattern on a typical day of the previous

week, accounted for 8 per cent of the male labour

force in both urban and rural India, and between 9

and 12 per cent of the female labour force, which

is truly remarkable, and very worrying in a country

that provides nothing in the form of unemployment

benefit or insurance.

But perhaps the most significant change of has been

in the pattern of employment. There has been a significant

decline in wage employment in general, which includes

both regular contracts and casual work. While regular

employment had been declining as a share of total

usual status employment for some time now (except

for urban women workers), wage employment had continued

to grow in share because employment on casual contracts

had been on the increase.

But the latest survey round suggests that even casual

employment has fallen in proportion to total employment.

In fact, the share of casual labour has fallen for

all categories of workers - men and women, in rural

and urban India. The sharpest decline has been in

agriculture, where wage employment in general has

fallen by a rate of more than 3 per cent per year

between 1999-2000 and 2004-05.

But even for urban male workers, total wage employment

is now the lowest that it has been in at least two

decades, driven by declines in both regular and casual

paid work. For women, in both rural and urban areas,

the share of regular work has increased but that of

casual employment has fallen so sharply that the aggregate

share of wage employment has fallen. So there is clearly

a real and increasing difficulty among the working

population, of finding paid jobs in any form.

This is probably the real reason why there has been

a very significant increase in self-employment among

all categories of workers in India. The increase has

been sharpest among rural women, where self-employment

now accounts for nearly two-thirds of all jobs. But

it is also remarkable for urban workers, both men

and women, among whom the self-employed constitute

45 and 48 per cent respectively, of all usual status

workers.

All told, therefore, around half of the work force

in India currently does not work for a direct employer.

This is true not only in agriculture, but increasingly

in a wide range of non-agricultural activities, and

in both rural and urban areas.

Self-employment is often eulogised as representing

an advance from the drudgery of paid work and the

possibly tyranny of employers. And of course there

are cases where self-employment is of this preferable

and more liberated variety, where the joys of being

one’s own boss more than compensate for the increased

insecurity of income and greater difficulties of arranging

the sale of one’s produced goods or services.

But the particular context in which self-employment

has arisen in India in recent years suggests that

these more positive experiences may account for only

a minority of increase in self-employment. Instead,

more and more working people are forced to work for

themselves because they simply cannot find paid jobs.

In the case of less educated workers without access

to capital or bank credit, this in turn means that

they are forced into petty low productivity activities

with low and uncertain incomes.

The latest NSS report confirms this, with some very

interesting information about whether those in self-employment

actually perceive their activities to be remunerative.

It turns out that just under half of all self-employed

workers do not find their work to be remunerative.

This is despite very low expectations of reasonable

returns - more than 40 per cent of rural workers declared

they would have been satisfied with earning less than

Rs. 1500 per month, while one-third of urban workers

would have found Rs. 2000 to be remunerative.

This new trend requires a significant rethinking of

the way analysts, policy makers and activists deal

with the notion of ''workers''. The older categories,

methods of analysis and policies become largely irrelevant

in this context.

For example, how does one ensure decent conditions

of work when the absence of a direct employer means

that self-exploitation by workers in a competitive

market is the greater danger? How do we assess and

ensure ''living wages'' when wages are not received

at all by such workers, who instead depend upon uncertain

returns from various activities that are typically

petty in nature? What are the possible forms of policy

intervention to improve work conditions and strategies

of worker mobilisation in this context?

This significance of self-employment also brings home

the urgent need to consider basic social security

that covers not just hired workers in the unorganised

sector, but also those who typically work for themselves.

This makes the pending legislation on social security

for workers in the unorganised sector especially important.

It is time we revised our labour policies to deal

more effectively with the changing circumstances.