Discussions

of GDP growth at both national and international levels

often get carried away by relatively recent trends.

But it is sometime useful to situate recent income

growth in the longer term context, if only to remind

ourselves of the structural processes involved.

It is also useful because the second half of the twentieth

century is generally perceived as the most dynamic

in the history of capitalism. It is also seen as a

period in which at least some developing countries

managed to improve their relative position in the

global income hierarchy, in different phases and through

different trajectories.

There are various ways in which this is supposed to

have occurred. Import substituting industrialisation

in the 1950s and 1960s played a role in diversifying

large developing and thereby generating a higher rate

of GDP growth. Oil exporting countries benefited from

the oil price increases of the second half of the

1970s, which enabled some of them top move to a higher

level of per capita income. According to some analysts,

the most recent "globalisation" phase of

the 1990s has enabled some countries – China and India

in particular – to benefit from more open global trade

and thereby increase per capita incomes and reduce

poverty.

All this would presumably have operated to create

more convergence of incomes between the developed

and developing worlds, even if in fits and starts,

such that the gap between per capita incomes of countries

across the world would start reducing. While this

can and has been examined with econometric analyses

of varying degrees of sophistication, it is also possible

to just look at the overall evidence on GDP growth

patterns from different sources.

Table 1 provides evidence on shares of various regions

over the period 1950-1998, of global population and

global GDP re-estimated according to Purchasing Power

Parity (PPP). These are based on data provided in

an OECD study by Angus Maddison (Angus Maddison: The

World Economy: A Millenial Perspective, OECD Paris

2001).

PPP estimates are used instead of nominal exchange

rates to compare income across economies, because

of the widely observed reality that currencies command

different purchasing power in different countries,

than is suggested by the nominal rates. However, there

are some well-known problems in the estimates of income

using exchange rates based on PPP, not least of which

are the issues of choosing comparable baskets of goods

and the poor quality of the data on actual prices

prevailing in different countries (including large

developing countries such as China and India) that

are used in such studies, which affect the reliability

of such calculations.

There is a less talked about but equally significant

conceptual problem with using PPP estimates. In general,

countries that have high PPP, that is where the actual

purchasing power of the currency is deemed to be much

higher than the nominal value, are typically low-income

countries with low average wages. It is precisely

because there is a significant section of the workforce

that receives very low remuneration, that goods and

services are available cheaply. Therefore, using PPP-modified

GDP data may miss the point, by seeing as an advantage

the very feature that reflects greater poverty of

the majority of wage earners in that economy.

Nevertheless, PPP-based estimates have been widely

used, even though they are likely to overestimate

incomes of working people in lower-income countries

for the reasons described above. Maddison's estimates,

presented in Table 1, allow us to track the relative

population and income shares by broad category of

country for the latter half of the 20th century.

Table

1: Shares

of global population and income in PPP terms |

|

Percent share of world population |

Per cent share of world output

in PPP terms |

|

Developed

Countries |

|

1950 |

19 |

57 |

|

1973 |

15.6 |

50.9 |

|

1998 |

12.1 |

45.6 |

|

Developing Countries |

|

1950 |

70.4 |

30 |

|

1973 |

75.2 |

36.1 |

|

1998 |

81 |

49 |

|

Eastern

Europe and Former USSR |

|

1950 |

10.6 |

13.1 |

|

1973 |

9.2 |

12.8 |

|

1998 |

6.9 |

5.4 |

|

Source:

Angus Maddison (2001) |

Table

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

It is evident that, as far as

the countries that were known as "developed"

in 1950 are concerned, there has been relatively little

change in the per capita income position vis-a-vis

the rest of the world, especially since the mid-1970s.

In 1950 the developed countries received nearly 60

per cent of global income, but they also accounted

for almost 20 per cent of world population. In the

twenty five years after 1973, the share of the income

of the developed countries fell by only 10 per cent,

or 5.3 percentage points, whereas the share of population

declined by 22 per cent or 3.5 percentage points.

So even in PPP terms, just above one-tenth of global

population in the developed countries still receives

nearly half the world's income.

Consider the same ratios for the developing countries

taken as a group. This category includes all the “success

stories” of the developing world in East Asia and

elsewhere, the socialist countries outside of Eastern

Europe and the former USSR as well as several oil-exporting

countries that have benefited from global oil price

booms. There has been some improvement in global income

shares for this group as a whole, but this has been

far outpaced by the growing share of the developing

world in global population. So, between 1950 and 1998

developing countries managed to increase their share

of global income by 15 per cent, or nearly 11 percentage

points, their share of global population increased

by a whopping 63 per cent, or 19 percentage points,

so that there was no relative increase in per capita

terms.

The countries of the former Soviet Union and Eastern

Europe have typically been treated as outside of both

these categories, and it is interesting to note how

this process worked out for these countries. Between

1950 and 1973, the conditions appeared broadly stable,

that is, there was a slight decline in both population

and global GDP shares. However, after 1973 – or more

accurately, probably after 1989 and the collapse of

the Berlin Wall – there has been a sharp decline in

population share (35 per cent, or 4 percentage points),

associated with an even sharper decline in income

share (59 per cent, or 8 percentage points).

Given all the problems of basing inter-country income

comparisons on PPP estimates, it is worth looking

at comparisons based on nominal exchange rates, which

do provide some idea of inter-country income differentials

especially in a world in which trade penetration is

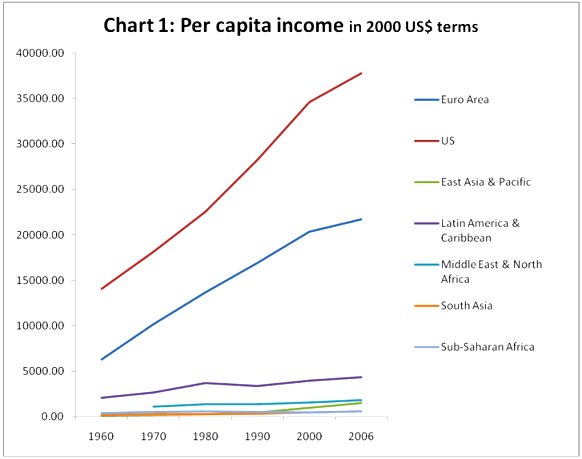

increasing. Chart 1 provides the evidence on per capita

incomes across some major countries and country groupings

for the period 1960-2006, based on the World Bank’s

World Development Indicators.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

This chart shows very clearly how large the global

income gaps are. The initial differences in per capita

incomes (in 1960 in this case) were so large that

even quite rapid increases in per capita incomes in

some regions over the subsequent four and half decades

have not managed to make the gap more repsectable.

Thus, while the per capita income of the fastest growing

developing region – East Asia – increased by more

than ten times over this period compared to an increase

of less than three times for the US, in 2006, the

average income for US was still fifteen times that

of East Asia.

For other developing regions the per capita income

gaps have been even larger and in some cases growing.

Thus, the per capita GDP in the current Euro area

in 1960 was 34 times that of South Asia; but by 2006,

it had increased to 36 times. For Sub-Saharan Africa,

the widening gap was even more stark. In 1960, the

per capita income of the countries that are now in

the Euro Area was 15 times that of Sub-Saharan Africa;

by 2006, the difference was as large as 38 times.

Latin America was then and remains the richest developing

region, yet the per capita income gaps between it

and both the US and the EU have increased in the past

forty six years. Even for countries in the Middle

East and North Africa, which contains several major

oil exporters, the income gaps have grown substantially

with respect to both the US and the Euro Area countries.

Another way of examining this is to look at the share

of countries or regions in world GDP in dollar terms,

rather than in PPP terms. It turns out that at nominal

exchange rates, the share of developing countries,

even the largest and most dynamic ones, remains quite

puny. Even in the first six years of this century,

after more than two decades of rapid growth in China

and India, the two countries account for less than

7 per cent of global GDP compared to 30 per cent for

the US (changed relatively little from the 1960s)

and 14 per cent for Japan. The share of China, India,

Brazil and Argentina together in 2000-06 was less

than 10 per cent.

This pattern is at least partly because the growth

performance of the developing world has been so uneven.

Within the developing world, only East Asia and the

Pacific and South Asia show any significant acceleration

of growth since the 1960s or indeed higher growth

rates than the developing world. Furthermore, it is

evident that for South Asia the acceleration is relatively

recent, so it is really only East Asia and the Pacific

that in the aggregate has shown rapid growth over

a prolonged period.

The other developing regions showed higher growth

rates during the import substitution phase, and do

not appear to have benefited much from the "globalisation"

phase in GDP growth terms. If the 1980s was a "lost

decade" for Latin America, with declines in real

GDP, the subsequent decade was not much better, especially

given the low base. Even the recent spurt has led

to average growth rates of less than 2 per cent per

annum. Meanwhile Sub-Saharan Africa has experienced

two lost decades, with average real GDP (in aggregate,

not per capita terms) falling continuously in the

1980s and the 1990s.

So the picture of a very dynamic and rapidly changing

world economy, in which developing countries are emerging

as the major players, may be overplayed. A longer

term perspective on growth suggests that for much

of the developing world, relative positions in the

international economy have hardly changed at all.