The

leaders of organised manufacturing in India complain

much. About intrusive government, inadequate economic

reform, overly high taxation, inflexible labour markets

and much else. Even if there is an element of truth

in any or all of these, this does not seem to have

affected the sector's ability to garner higher profits

in the years after liberalisation. The sector seems

to have done extremely well for itself since the early

1990s.

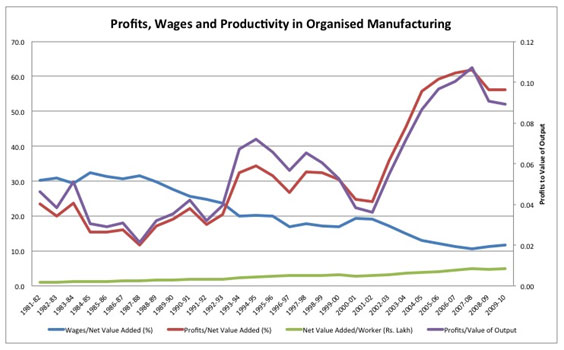

Consider trends emerging from the official Annual

Survey of Industries relating to the organised manufacturing

sector depicted in the accompanying chart.

Chart

1 >> (Click

to Enlarge)

To start with, since the early 1990s, when liberalisation

opened the doors to investment and permitted much

freer import of technology and equipment from abroad,

productivity in organised manufacturing has been almost

continuously rising. Net value added (or the excess

of output values over input costs and depreciation)

per employed worker measured in constant 2004-05 prices

(represented by the green line), rose from a little

over Rs. 1 lakh to more than Rs. 5 lakh. That is,

productivity as measured by net product per worker

adjusted for inflation registered a close to five-fold

increase over this 30-year period. And more than three-fourths

of that increase came after the early 1990s.

Unfortunately for labour, and fortunately for capital,

the benefit of that productivity increase did not

accrue to workers. The average real wage paid per

worker employed in the organised sector, calculated

by adjusting for inflation as measured by the Consumer

Price Index for Industrial Workers [CPI(IW) with 1982

as base], rose from Rs. 8467 a year in 1981-82 to

Rs. 10777 in 1989-90 and then fluctuated around that

level till 2009-10. The net result of this stagnancy

in real wages after liberalisation is that the share

of the wage bill in net value added or net product

(the blue line), which stood at more than 30 per cent

through the 1980s, declined subsequently and fell

to 11.6 per cent or close to a third of its 1980s

level by 2009-10.

A corollary of the decline in the share of wages in

net value added was of course a rise in the share

of profits (red line). However, the trend in the share

of profits is far less regular than that of the other

components in net value added. Between 1981-82 and

1992-93, the ratio of profits to net value added fluctuated

between 11.6 per cent and 23.4 per cent. During much

of the next decade (1992-93 to 2002-03) it remained

at a significantly higher level, fluctuating between

20.4 per cent and 34.3 per cent, but showed clear

signs of falling during the recession years 1998-99

to 2001-02.

However, the years after 2001-02 saw the ratio of

profit to net value added soar, from just 24.2 per

cent to a peak of 61.8 per cent in 2007-08. These

were indeed the roaring 2000s! Unfortunately for manufacturing

capital, the good days seem to be at an end. There

are signs of the profit boom tapering off and even

declining between 2006-07 and 2009-10. But this latter

period being short, we need to wait for more recent

ASI figures to arrive at any firm conclusions.

As of now, what needs explaining is the remarkable

boom in profits at the expense of all other components

of net value added. An interesting feature that emerges

from the chart is the fact that the ratio of profits

to value of output (violet line), or the margin on

sales, tracks closely the irregular trend in the share

of profits in value added described above. Increases

in profit shares have clearly been the result of a

rise in the mark up represented by the profit margin

to sales ratio, or the ability of capital to extract

more profit from every unit of output.

Interestingly, the periods in which the ratio of profits

to the value of output has risen, leading to sharp

increases in profit shares, were also the years when

the two post-liberalisation booms in manufacturing

occurred. The first of those was the mini-boom of

the mid-1990s, starting in 1993-94 and going on to

1997-98, which was fuelled by the pent-up demand in

the upper income groups for a range of goods that

had remained unsatisfied prior to the liberalisation

of imports and foreign investment rules. The second

was the stronger and more prolonged boom after 2002-03,

led by new sources of demand, which was arrested by

the global financial crisis in 2008-09. The coincidence

of the profit and the output booms suggests that,

in periods of rising demand, the organised manufacturing

sector in India has been able to exploit liberalisation

in two ways. First, it has been able to expand and

modernise using imported technologies, raising labour

productivity significantly in the process. Secondly,

it has been able to ensure that the benefit of that

productivity increase accrues almost solely to profit

earners, because of the conditions created by the

''reformed'' economic environment.

As a result, the mark up rose significantly or sharply

in these periods and delivered a profit boom. The

evidence is clear. Big industrial capital has been

a major beneficiary of reform. Its complaints are

not to be taken too seriously.

*

This article was originally published in the Hindu,

10 May 2012, and is available at

http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/Chand

rasekhar/article3403450.ece