Since

euphoria over the BSE Sensex breaching one more psychological

barrier, the 8000 mark, preoccupies the media, new

signs of economic vulnerability remain unflagged and

ignored. According to the latest trade statistics

released by the Directorate General of Commercial

Intelligence and Statistics relating to the first

five months of this financial year (April-August),

the deficit in India's merchandise trade stood at

$17431.2 million as compared with $9728.5 during the

corresponding period of the previous year. This 80

per cent increase in the deficit, if it persists over

the rest of the year, could take India's trade deficit

to close to $50 billion over the financial year 2005-06.

It could be argued that such an increase was inevitable

given the sharp increase in the international prices

of oil, which was and is expected to substantially

increase India's oil import bill. Indeed, over the

first five months of this financial year, oil imports

rose in value by close to 37 per cent, rising from

$12002 million to $16428 million. However, what is

noteworthy is that over the same period non-oil imports

also rose by a similar 37 per cent from $26803 million

to $37763 million. In the event, despite a creditable

23 per cent increase in the dollar value of India's

exports during April-August 2005, the trade deficit

has widened substantially. Even if the increase in

the oil import bill is seen as temporary because oil

prices must moderate and even fall, the same cannot

be said of the non-oil import bill. Clearly import

liberalisation has meant that any buoyancy in the

economy, even if it is not focussed on the commodity

producing sectors, results in import bill increases

that match those generated by events like the current

oil shock. If that increase has to be moderated or

reversed for any reason, lower economic growth must

be the price that has to be paid.

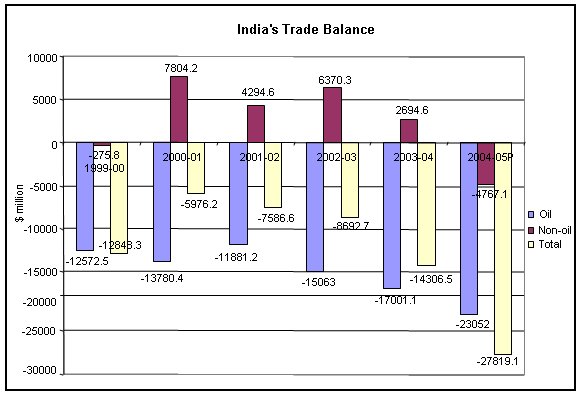

The full significance of this trend comes through

when we note that one comforting feature of India's

balance of trade between 2000-01 and 2003-04 has been

the surplus on the non-oil merchandise trade account

(see Chart). That surplus helped partially moderate

the effects of a rising oil trade deficit, which rose

sharply between 2001-02 and 2004-05, partly because

of a gradual increase in oil prices and partly as

a result of dramatic increases in the domestic consumption

of oil and oil products. However, in 2004-05, the

non-oil trade balance was once again negative, removing

the partial cushion offered by the trade in non-oil

products against the effects of a rising oil trade

deficit at a time when the rise in oil prices was

sharper. What is happening is that, in a period when

oil prices have registered particularly sharp increases,

the non-oil import bill has kept pace with the oil

import bill, resulting in a massive widening of the

deficit on the merchandise trade account.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

It is of course true that even during the previous

two financial years, the widening deficit on the trade

account was not a cause for concern because of significant

inflows of foreign exchange on account of remittances

and exports of software and IT-enabled serves. According

to the Reserve Bank of India, private transfers brought

in a net amount of $20.5 billion during 2004-05 and

software services exports contributed another 16.6

billion dollars. This net inflow went a long way towards

financing India's foreign exchange requirement in

that year on account of the merchandise trade deficit

and the deficit under other items of what are termed

''invisibles''. As a result, the deficit on the current

account of the balance of payments was relatively

small. Since India has also been a net recipient of

substantial capital inflows on account of debt and

foreign direct and portfolio investment, this led

to a huge accumulation of foreign exchange reserves

that implied a comfortable balance of payments situation.

It now appears that India's relatively strong current

account position is weakening rapidly. As noted above

a combination of rising oil prices and dramatic increases

in non-oil imports is resulting in a substantial widening

of the merchandise trade deficit. Simultaneously,

there is evidence that recent increases in remittance

inflows are tapering off. Net remittances, which rose

from $16.4 billion in 2002-03 to $22.6 billion in

2003-094, was down to $20.5 billion in 2004-05. While

net revenues from software services, continue their

increase from $8.9 billion in 2002-03 to $11.8 billion

in 003-04 and $16.6 billion in 2004-05, the current

account can be expected to widen because of the other

two developments.

Consequently, a greater share of the net capital flows

that India attracts in the form of debt and foreign

direct and portfolio investment would now be needed

to finance the current account deficit. This would

be perfectly acceptable if these capital inflows were

being used to build productive capacities that can

support exports and earn the foreign exchange needed

to meet future foreign repayment commitments that

today's inflows imply. That, however, is clearly not

happening. Portfolio flows create no additional capacities,

though FII investments drive the current stock market

boom and create the euphoria that explains the lack

of concern about potential external vulnerability.

And to the extent that foreign debt and direct investment

inflows are indeed creating new capacities, they are

not generating export revenues to finance the rising

non-oil and oil import bill.

This is not surprising. It has been clear for some

time now that unlike what occurred in the late 1980s

and early 1990s in second-tier East Asian industrialisers

like Thailand and Malaysia, and very much unlike what

has been happening in China for close to a decade-and-a-half

now, ''non-financial'' investments financed with foreign

capital in India have not been directed at greenfield

projects that contribute to an expansion of exports.

Rather, they have principally been: (i) directed at

increasing the share of foreigners in firms they already

control consequent to the relaxation of ceilings on

foreign holdings in domestic joint ventures catering

to the domestic market; (ii) used for acquisitions

of local firms that provide foreign investors with

a share in the domestic market for a range of products;

and (iii) concentrated in greenfield projects in infrastructural

services such as power and telecommunications, which

in any case are sectors that produce ''non-tradables'',

or services that are not normally exported to foreign

markets.

The only area in which an increase in foreign presence

involves export revenues as a rule is the software

and IT-enabled services sector. But even though export

revenues from this sector have been rising rapidly,

the sector is still too small to make up for the foreign

exchange profligacy of the rest of the economy. Overall

import liberalisation, combined with a concentration

of incomes in sections of the population with a significant

pent-up demand for imported or import-intensive goods,

has resulted in an excess of demand for foreign exchange

relative to current account earnings.

The incipient tendency towards external vulnerability

that this entails has thus far been ignored for two

reasons. First, India's exports have been performing

better in recent years than they did in the past.

Second, India has been such an attractive destination

for foreign financial investors that inadequacy of

foreign exchange has become a feature of a rarely

remembered past.

Other than for 2001-02, when India's exports declined

marginally, exports in dollar terms have been rising

at over 20 per cent an annum over most years of this

decade. This has been the focus of statements by Commerce

Ministry spokespersons. As and when any reference

is made to import growth, a rise in the import bill

is presented more as evidence of recovery in the industrial

sector, rather than as a cause for concern because

that rate has implications for the merchandise trade

deficit.

Implicit in this view is the belief that a trade deficit

does not matter, since invisible revenues ensure that

a rise in the trade deficit does not automatically

translate into a rise in the current account deficit

and that, even if it does, capital flows are more

than adequate to cover the likely increase in the

current account deficit. Recent experience has shown

that the import surge is such that even with reasonable

export growth this view is no longer true. What is

more, periodic currency crises elsewhere in the world

suggest that reliance on purely hot money flows to

finance such a current account deficit is by no means

a sensible strategy.

But there is a more fundamental problem here. The

success of any liberalisation strategy depends in

the final analysis on the realisation of a rate of

export growth that can deliver growth without balance

of payments problems that are structural. This makes

comparisons of the rate of export growth over time

meaningless. Allowing for a reasonable lag, what is

needed is a rate of export growth at any point of

time that covers the increase in imports that liberalisation

involves as well generates the revenues needed to

meet commitments associated with capital inflows.

It would be absurd to use more capital inflows to

cover past capital flow commitments, since this involves

a spiral of dependence on capital inflows. Such dependence

implies even greater fragility if such capital flows

are of a kind that are footloose and investors can

exit the country with as much enthusiasm as they showed

when they entered.

What the evidence on India's trade trends suggest

is that even as dependence on volatile capital flows

increases, an export growth rate that is presented

as creditable appears increasingly adequate to cover

the import surge in non-oil imports. Add on a surge

in the oil import bill and that inadequacy is all

the greater. This implies that the dependence on volatile

flows to sustain the balance of payments is rising.

If the current boom in the stock market reaches its

inevitable peak, then not only will new capital flows

dry up but past capital flows would seek to exit the

country. That is a denouement that must be avoided

if India is not to follow the example of ''emerging

markets'' like Mexico, South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia,

Malaysia, Brazil, Turkey and Argentina. If it does,

then it could be the next case where a financial crisis

can be the means to ensure neo-colonial conquest of

a country whose elite sees itself as populating a

rising global power.