It

is not just a revamp, claims the government, but altogether

new. After many rounds of reduction of the marginal

tax rate and years of tinkering with the structure

of direct taxes it claims to have decided to drastically

alter the direct tax regime. To that end it has launched

a debate that would lead up to the introduction of

legislation to put in place a new direct tax code.

The discussion paper accompanying the draft code attempts

to draw attention to a number of features of the new

code: the definition of income, clarity regarding

who can be taxed and the treatment of exemptions.

But discussion on the code is likely to be dominated

by the extent of taxation of personal and corporate

incomes that the new regime would involve.

In this regard there is one aspect of the new code

that is welcome. It seeks to rationalize the innumerable

tax exemptions given to both high-income personal

income tax payers and corporations. The consequence

of this would be enhanced revenue generation and a

greater degree of transparency in the tax structure.

It would also possibly lead to greater equity, since

most tax exemptions are either directed at or more

easily exploited by those in higher income tax brackets.

Budget documents for 2009-10 estimate that the “tax

expenditures” on account of foregone taxes during

2008-09 amounted to Rs. 68,914 crore in the case of

corporate taxes, Rs. 5116 crore in the case of non-corporate

(partnerships, associations of persons, bodies of

individuals) tax payers and Rs. 34,437 crore in the

case of income taxes. This amounts to around 17 per

cent of the gross tax revenues which accrued to the

central government according to the revised estimates

for that year. Recouping a significant share of this

would make a considerable difference to the budgetary

position of the government and increase its fiscal

manoeuvrability.

However, if this and greater transparency and equity

were the objectives that the government was pursuing

then a revamp of the existing tax law to get rid of

a wide range of unnecessary exemptions would have

been adequate. That the government is pursuing objectives

other than these is clear from its unorthodox decision

to include in the documents for discussion on the

proposed Direct Tax Bill a proposal for a new structure

of direct tax rates. That structure could lead to

a sharp reduction of taxes currently paid by individuals

and corporates in different tax brackets under the

present tax regime.

The way this is to be ensured is a significant widening

of the tax slabs leading to a situation where individuals

would pay only 10 per cent tax as long as they remain

in the slab Rs.1,60,000 to Rs. 10,00,000, 20 per cent

in the slab Rs.10,00,000 to Rs. 25,00,000 and 30 per

cent thereafter. Further, the corporate tax rate is

to be reduced from 30 per cent to 25 per cent and

the minimum alternate tax (MAT) is to be calculated

on the value of gross assets, 2 per cent of which

will have to be paid at the minimum by all non-banking

companies.

Currently, the income tax payer pays 10 per cent tax

on income between Rs. 1.6 lakh and Rs. 3 lakh, 20

per cent between Rs. 3 lakh and Rs. 5 lakh, and 30

per cent beyond Rs. 5 lakh. This means, for example

that an individual who earns a lakh of rupees every

month by way of taxable salary will see a substantial

reduction in the amount of income tax paid. Moreover,

the ceiling on tax-free acquisition of savings instruments

has been increased from Rs.1 lakh to Rs. 3 lakh, even

though the range of instruments eligible for that

concession has been reduced.

By specifying these rates and ranges, even while indicating

that they are also subject to discussion, clearly

ties the hand of the government. Taxes, which are

increasingly seen as “hurting” the tax payer and not

as financing beneficial public provision, are such

that once the government proposes a level it can go

downwards from there but not upwards without opposition.

This implies that the government has chosen to significantly

cut rates by widening tax slabs and adjusting the

number of rates.

The government’s own view is that such comparisons

between the proposed direct tax regime and the existing

one are not valid, because what we have is a structural

transformation in regime. One way of interpreting

that statement could be that it is implicitly declaring

that the potential reduction in revenues as a result

of wider slabs and lower rates would be more than

neutralised by the reduction in exemptions under the

proposed regime and by the increased compliance that

a lighter tax regime would encourage. For example

salaries in the private sector are expected to be

computed on a cost-to-company basis and the imputed

rental value of rent free accommodation (for example)

is to be treated as part of the salary.

The danger here as can be seen even in the early responses

to the draft code is that the debate in the run up

to legislative action would force the restoration

of a range of exemptions while sticking with the proposed

new slabs and rates. Moreover, monitoring whether

value of perquisites are actually computed and included

in salary would be difficult and evasion through such

exclusion can be as much or higher than in the case

of evasion of post-exemption income and tax calculations.

The expected quid-pro-quo may not materialise and

revenues may in fact decline.

Given this, the belief that the new code would contribute

to an increase in tax collections is largely based

on the faith that reduced tax rates would contribute

to better compliance. Needless to say, this faith

in the “Laffer curve” is neither theoretically nor

empirically grounded. In the event, the new tax code

is ill-advised for at least two reasons. The first

is that it comes at a time when despite the consensus

that public capital formation and public expenditure

on social infrastructure and social protection are

grossly inadequate in India, the deficit in the budget

of the central government is rising. Even though there

are expectations that the deceleration in growth in

India induced by the global crisis is hitting bottom,

there is substantial agreement that the government

must keep expenditure high if the rate of growth is

not to slump further. This would lead to inflation

if it is financed by borrowing rather than by a draft

on private savings through taxation given the fact

that food price inflation is already high and a truant

monsoon is likely to intensify supply constraints.

This then is the least propitious time to launch an

adventurous experiment in resource mobilisation involving

a cut in direct tax rates.

But the case against the code is not just short term.

It would also abort the much-needed correction of

the decline and stagnation of the tax-GDP ratio at

the centre. One striking feature of the 1990s, which

was the first decade of accelerated economic reform,

is that despite evidence of reasonably good growth

rates and signs of growing inequality, there was no

improvement in the Centre’s ability to garner a larger

share of resources to finance expenditures it considered

crucial. Even when corporate profits and managerial

salaries were reported to be rising sharply, taxes

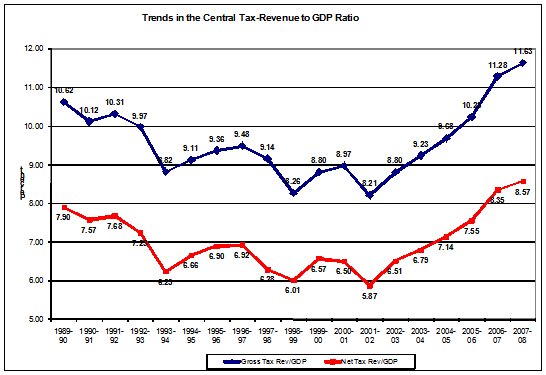

did not appear as buoyant. The Central tax GDP ratios

in India were declining for much of this period. And

despite the increase in the ratio in recent years,

they exceeded the level they were at in 1989-90 only

in 2006-07 (Chart ). Despite high growth, improved

profitability and signs of increased inequality (which

should improve tax collection), the increase has been

adequate to just about put the tax GDP ratio back

to its immediate pre-liberalisation levels. Thus an

effort to raise this ratio even further is what is

called for.

If these imperatives have been ignored in the new

code it must be because of the view that households

taxed lightly would increase their consumption and

firms taxed lightly would invest more, and enhance

consumption and investment would drive growth. There

are three problems with this argument. First, it underestimates

the role that public expenditure in general and public

capital formation in particular plays in crowding

in private investment, as amply illustrated by past

Indian experience. Second, it privileges GDP growth

even at the cost of reducing the role of direct taxation

in moderating the inequalising character of recent

economic growth. Finally, it completely ignores the

important role of tax-financed public expenditure

in alleviating poverty, providing social protection

and advancing human development.

The tax code is a signal that UPA II plans to continue

with the policy of cajoling private capital into investing

for growth with concessions that have adverse equity

and welfare implications.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge