On

April 4, the US Department of Commerce succumbed to

protectionist pressures and chose to launch investigations

to check whether textile imports from China were disrupting

US markets. US Commerce Secretary, Carlos Gutierrez,

is reported to have said that the decision was the

first step in a process to determine whether the US

market for these products is being disrupted and whether

China is playing a role in that disruption. The immediate

excuse was evidence of a sharp rise in the quantum

of imports of certain varieties of Chinese textiles

into the US market, quota restrictions on which under

the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA) were lifted as of

January 1, 2005. As Table 1 indicates, import increases

during the first quarter of the year in select categories

that are controversial have varied from an excess

of 250 per cent to as much as 1600 per cent. However,

there is need for caution when quoting these figures,

because they are growth rates computed on a base kept

low by the MFA's quota regime.

Table

1: Increase in Imports of Specific Categories

of Textiles: Jan-March 2005 |

Category |

Volume

Growth (Percentage)

|

|

|

Cotton

Hosiery |

1084

|

Cotton

Knit Shirts, MB |

1003

|

W/G

Knit Blouse |

1499

|

Cotton

Skirts |

1102

|

Cot.M/B

Trousers |

1492

|

W/G

Slacks, etc. |

1612

|

Cotton

Underwear |

408

|

M-MF

Underwear |

260

|

Table

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

But

touting such figures, US industry associations have

been accusing the Chinese of dumping to an extent

that disrupts the US market and damages the domestic

industry. In the event, they are demanding that the

government should invoke a clause included in China's

WTO accession conditions that permits the US government

to restrict import growth to 7.5 per cent a year till

2008. The Bush government that has recently begun

its second term has been quick to oblige, even though

domestic political pressures are not as overwhelming.

There are, however, a number of reasons to hold that

the US response is either alarmist or orchestrated

to justify a protectionist response. We must recognise

that quotas under the MFA, which limited the quantum

of exports into individual segments of the global

textile market from the most competitive textile exporters,

had two kinds of effects. First, it reduced the competition

faced by US (domestic) suppliers of textiles from

imports from the most cost-competitive centres of

global textile production, allowing the former to

sustain higher levels of output. Second, it reduced

competition between exporters from more and less competitive

locations targeting the same market, by restricting

the volume of exports from more competitive producers.

As a result of these two different forces at play,

the lifting of quotas was expected to have two different

effects. One was an increase in the total quantum

of imports of restricted items into individual markets

because of increased imports from all locations that

are cost-competitive relative to domestic suppliers.

The second was a re-division of an individual market

among exporters, with more cost-competitive suppliers

displacing less cost-competitive ones in individual

segments.

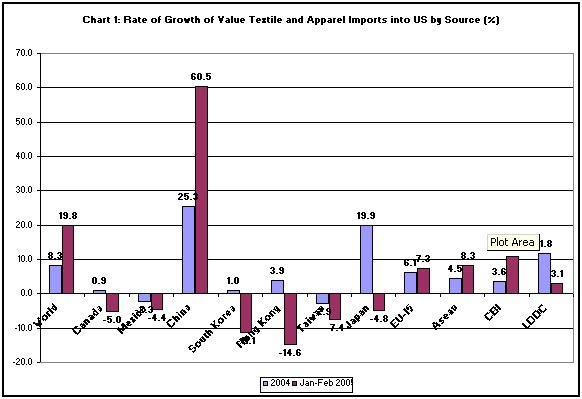

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

As Chart 1 makes clear, both these tendencies are

visible in the US market. Considering all items of

textile and apparel imports, the US trade balance

report which provides the most comprehensive data,

indicates that total imports into the US market rose

by close to 20 per cent in the first two months of

2005 (relative to the corresponding period of the

previous year) as compared with 8.3 per cent during

2004. Thus the removal of quotas did result in a substantial

increase in imports into the US market that would

have resulted in some displacement of domestic production.

However, the increase in imports from China, which

amounted to 60.5 per cent during January-February

2005 as compared with 25.3 per cent in 2004, was not

wholly directed at the displacement of US production.

Rather, increased imports from China were accompanied

by a decline or slowing down of imports from other

sources such as Mexico, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan

and Japan. That is, after the removal of quotas, Chinese

imports were outcompeting imports into the US from

other sources that were earlier “protected” by the

MFA regime.

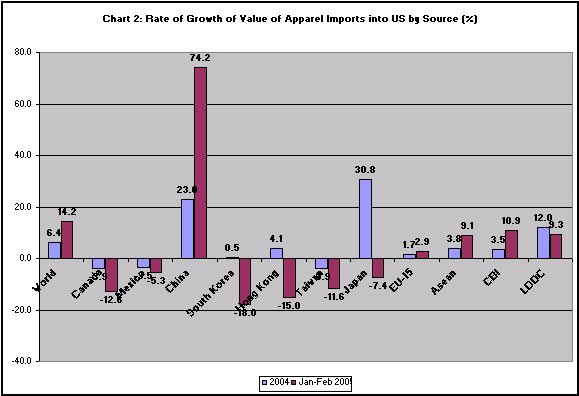

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

This is not to say, however, that China is wiping

the floor clean. There are other countries such as

the EU-15, the ASEAN countries and countries belonging

to the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) that have

been able to increase the rate of expansion of their

exports. What is disconcerting however is that the

Least Developed Countries (LDCs), which do not receive

the same special benefits as the CBI group in US markets,

have seen a significant decline in the rate of growth

of their exports to the US market. But this may partly

be due to the disruption caused by the tsunami in

at least some of these countries, such as Mauritius.

Some of these features are sharper if we consider

an area like apparel, which is where the bulk of the

increase in imports into the US from China has taken

place. As Chart 2 indicates, while China's apparel

exports to the US grew by close to 75 per cent during

the first two months of 2005, as compared with 23

per cent during 2004, this was accompanied by a substantial

degree of displacement of imports from Canada, Mexico,

South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Further, besides

increases in imports from country-groupings such as

the EU-15, ASEAN and the CBI, LDCs have registered

a much smaller decline in the rate of growth of imports

than is suggested by aggregate figures.

In sum, not all of China's dramatic export increase

during the first quarter of 2005 was on account of

the displacement of US production. It was partly because

of displacement of export increases from other countries.

And there were countries other than China which contributed

to the growth in overall textile imports into the

US. Above all, as Table 2 makes clear, the effect

of the increase in Chinese exports on exports to the

US from individual developing countries has not been

as adverse as had been expected.

Table

2: US Textile Imports by Country Major Shipper's

Report ($ Mill.) |

|

|

|

|

|

Growth

Rate |

|

2003 |

2004 |

Jan-Feb

2004 |

Jan-Feb

2005 |

Jan-Feb

2004 |

Jan-Feb

2005 |

World |

77434 |

83312 |

12284.1 |

14010

|

7.6 |

14.0 |

China |

11608.8 |

14559.9 |

2002.9 |

3362.4

|

25.4 |

67.9 |

Asean |

11678.2 |

12143.6 |

1867.7 |

2014

|

4.0 |

7.8 |

CAFTA |

9244.6 |

9578.6 |

1266.9 |

1408.4

|

3.6 |

11.2 |

EU-15 |

4336.5 |

4530 |

687.5 |

730.9

|

4.5 |

6.3 |

Sub-Sahara |

1534.9 |

1781.8 |

253.2 |

282.5

|

16.1 |

11.6 |

Bangladesh |

1939.4 |

2065.7 |

324.6 |

359.4

|

6.5 |

10.7 |

Cambodia |

1251.2 |

1441.7 |

234.3 |

259.1

|

15.2 |

10.6 |

Fiji |

79.6 |

85.8 |

13.9 |

7.7

|

7.8 |

-44.6 |

India |

3211.5 |

3633.4 |

588.1 |

737

|

13.1 |

25.3 |

Indonesia |

2375.7 |

2620.2 |

445.4 |

477.6

|

10.3 |

7.2 |

Japan |

522.4 |

641.7 |

78.3 |

79.8

|

22.8 |

1.9 |

South

Korea |

2567 |

2579.7 |

393.9 |

344.3

|

0.5 |

-12.6 |

Laos |

3.9 |

2.1 |

0.3 |

0.1

|

-46.2 |

-66.7 |

Malaysia |

737.5 |

764.3 |

117.3 |

109.8

|

3.6 |

-6.4 |

Maldives |

93.7 |

81 |

12.5 |

4.7

|

-13.6 |

-62.4 |

Mauritius |

269.1 |

226.6 |

43.1 |

37.5

|

-15.8 |

-13.0 |

Mexico |

7940.8 |

7793.3 |

1144.9 |

1097.2

|

-1.9 |

-4.2 |

Mongolia |

181.1 |

229.1 |

25.8 |

21.7

|

26.5 |

-15.9 |

Nepal |

155.3 |

130.6 |

25.9 |

16

|

-15.9 |

-38.2 |

Pakistan |

2215.2 |

2546 |

371.4 |

396.9

|

14.9 |

6.9 |

Philippines |

2040.3 |

1938.1 |

323.6 |

299.9

|

-5.0 |

-7.3 |

Singapore |

270.8 |

244.1 |

34.1 |

34.1

|

-9.9 |

0.0 |

Sri

Lanka |

1493 |

1585.2 |

258.6 |

305.5

|

6.2 |

18.1 |

Taiwan |

2185 |

2103.9 |

308.3 |

283.6

|

-3.7 |

-8.0 |

Thailand |

2071.7 |

2198.2 |

314.1 |

372.8

|

6.1 |

18.7 |

Vietnam |

2484.3 |

2719.7 |

361.8 |

430.2

|

9.5 |

18.9 |

Table

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

What needs to be noted is that the displacement of

US production, to the extent that it occurred, is

a sign that the US has not adequately restructured

its industry during the long years of protection resorted

to for this very purpose. The protection afforded

to developed country textile production with the aim

of restructuring those industries began in the 1961,

when the Long Term Agreement on textiles was signed.

That agreement provided the developed countries with

a 10-year respite, during which they were expected

to either phase out a part of their uncompetitive

textile production, “burdened” by high wages, or modernise

their textile industries to render them competitive.

The promise to do away with protection in ten years

did not materialise. Protection was continued under

the Multi-Fibre Agreement, which was once more scrutinised

for phase-out under the Uruguay Round Agreement of

1994. But even under that agreement, the phase-out

of quotas was back-loaded, with quotas on close to

half of global textile trade kept in place till January

1, 2005. It is well known that most developed countries

first lifted quotas on items of less relevance to

developing country trade, reserving true liberalisation

till the beginning of 2005.

What the first-quarter surge in textile exports to

the US indicates is that despite 45 years of protection

expressly justified by the need to restructure the

industry, the US has not done so, unlike countries

such as the UK whose dependence on textiles during

the early stages of their industrialisation was even

greater. But the US is not the only culprit. Even

countries in the EU (such as France and Italy) are

using the US resistance to the Chinese export surge

as the basis for a demand for greater protection for

their own textile production. The European Union's

trade commissioner, Peter Mandelson, has been resisting

pressure to impose restrictions on Chinese textile

imports, on the grounds that the available evidence

of market disruption is inconclusive and could not

justify curbs for the time being. However, his ambivalent

postures, resulting from differences within the Community,

suggest that the EU too might resort to import curbs.

Responding to calls from countries like Sweden not

to impose such curbs, since that would amount to protectionism,

Mandelson declared: We should not confuse protection

with protectionism.

All this controversy arises despite efforts by China

to dampen the growth of its textile exports since

January 2005 to temper the reaction to likely export

increases. In December 2004, China imposed export

tariffs of Rmb0.2-Rmb0.3 per item in some cases and

Rmb0.5 per kilogramme in others in response to concerns

in the US and Europe that Chinese textile exports

might surge following the expiry of quotas on January

1. Now, China is contemplating further export tariffs.

Expectations are that China might raise export tariffs

by as much as Rmb2-Rmb4 per piece. Such action is

being contemplated despite the danger that Chinese

exporters are likely to be badly hit, because prices

for garment orders are fixed several months before

shipment.

China's need to bend over backwards to placate the

US results from three factors. First, China's own

dependence on the US market for exports that have

become a major engine for its growth. Second, the

huge trade and current account deficit on the US balance

of payments, which is resulting in a depreciation

of the dollar and rising the spectre of a financial

crash and global recession. Third, the huge US trade

deficit with China that the former wants to reduce

by getting China to revalue its currency. The message

is clear, if developing countries record a deficit

on their balance of payments it is their problem and

a reflection of their mismanagement. If the US records

a deficit on it external account that is everybody's

problem and a reflection of a global “imbalance” that

needs correction.

Unfortunately, imposing curbs on Chinese textile imports

into the US or the EU may not resolve the problem

either of unemployment in the US and EU textile industries

or the deficit on the US trade account. It would merely

serve to increase textile exports from other developing

countries to the US and EU. But the fact that this

could be used to divide developing country exporters

and win the support from some of them in the battle

against China may suit the US and EU. It helps win

allies in the battle to force China to turn inwards

rather than grow on the basis of burgeoning exports.

Globalisation is good only when the US-and perhaps

the EU-reaps its benefita. If that does not happen,

protectionism or voluntary export restraint is the

preferred alternative.