It

has been some time now since the government has stopped

bothering too much about the balance of payments.

Indeed, the continuous and even excessive build-up

of foreign exchange reserves (which now stand at more

than $310 billion, making India’s holding the fourth

largest in the world) suggests that the problem may

be one of plenty rather than scarcity, far removed

from the days when the foreign exchange constraint

was seen as binding upon domestic economic growth.

This has led to an attitude of complacency, not only

among policy makers but even among the wider public,

whereby balance of payments issues are rarely taken

as potential problems. It is even common to hear the

argument that the best way to manage the current inflation

within the country is simply to liberalise imports

further, on the assumption that our foreign exchange

situation is presently quite comfortable. Yet this

argument is flawed not only because it ignores the

potential damage to domestic activity and employment

from more imports, but because it underestimates the

fragility of recent tendencies in the balance of payments.

In fact, there are several sources of concern in the

recent pattern of external payments. The build-up

of reserves has been led by substantial inflows in

the capital account, which are either debt-creating

or inherently short-term and speculative in nature.

And this has been accompanied by the emergence and

increase in current account deficits, which make India’s

foreign reserve accretion fundamentally different

from and more problematic than it is in other countries

with large reserves, such as Japan and China.

For much of the past decade, India’s current account

was in surplus, because the trade deficits were more

than compensated by substantial increases in remittances

from workers abroad and software exports. However,

in recent years deficits have emerged, largely because

of the significant growth in trade imbalance. In the

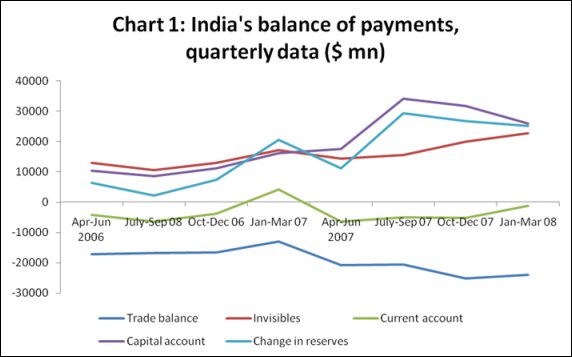

past two years, as Chart 1 shows, the current account

has been in deficit in almost every quarter, and the

imbalance has widened sharply in 2007-08.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart 1 also shows the very significant role played

by net invisibles, which have been growing continuously

in almost every quarter. The trade balance, by contrast,

has been deterioriating, and quite sharply after April

2007. This has led to a trade deficit for the entire

financial year 2007-08 of more than $90 billion. The

increase in net invisibles has not been enought to

counteract this, so that the total current account

deficit for the year was $17.4 billion. By the last

quarter of 2007-08, this meant that the current account

deficit amounted to 1.6 per cent of GDP, and the trade

deficit alone amounted to 8.4 per cent of GDP!

This is the trade deficit based on the RBI’s figures,

which are quite different from the commercial data

released by the DGCI&S. Indeed, the difference

between the import data from the two sources has grown

from $5.5 bn in 2006-07 to $12.8 bn in 2007-08. This

is largely because the RBI data include some imports

made by government (including of defence equipment

and the like) that do not go through the customs process

and are therefore not recorded by the DGCI&S.

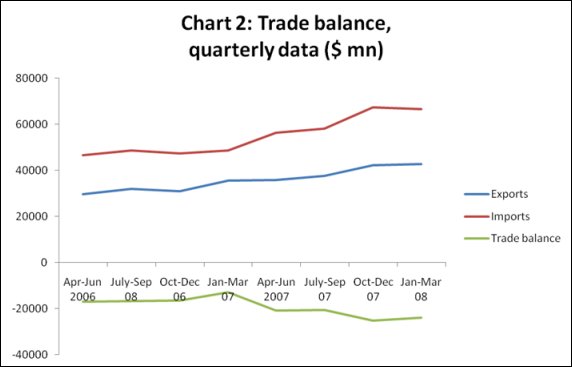

The worsening of the trade balance has been rapid

after March 2007, as indicated in Chart 2. This is

essentially because of a sharp acceleration in imports,

since exports continued to grow at more or less the

same rate as before. Over the year, exports increased

(in dollar terms) by 24 per cent but imports increased

by 30 per cent.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

It is often believed that the rapid growth of imports

in 2007-08 was essentially because of the dramatic

increase in oil prices, which naturally affected the

aggregate import bill. Certainly this played a role,

but some non-oil imports also increased rapidly. Therefore,

while oil imports in the last quarter of 2007-08 were

89 per cent higher (in US dollar terms) than in the

same quarter of the previous year, non-oil imports

were also higher by 31 per cent.

Table 1 provides an idea of the commodity categories

that were the main drivers of export and import growth

over the past year. The most rapid growth of exports

was for agricultural commodities, which is a circumstance

with both positive and negative features. The export

of engineering goods was also quite rapid, as were

exports of gems and jewellery and chemicals. Agricultural

goods were dominantly exported to West Asia, whereas

engineering goods and ores and minerals were increasingly

exported by India to China.

Table

1:

Important Trade

Items in 2007-08 |

|

Share %

|

Growth %

|

|

Exports |

|

Engineering goods |

20.91 |

11.65 |

|

Petroleum products |

15.64 |

18.46 |

|

Gems &

Jewellery |

12.36 |

9.47 |

|

Chemicals & related

products |

13.63 |

4.71 |

|

Textiles |

11.38 |

-2.08 |

|

Agriculture & allied

products |

8.43 |

37.16 |

|

Ores & minerals |

5.66 |

14.42 |

|

Leather & leather

goods |

2.16 |

1.21 |

|

Electronic goods |

2.11 |

1.48 |

|

Imports |

|

Petroleum products |

32.75 |

34.97 |

|

Machinery |

13.81 |

23.94 |

|

Electronic goods |

8.55 |

27.77 |

|

Gold |

7.08 |

17.5 |

|

Iron & steel |

3.53 |

41.12 |

|

Pearls, precious &

semi-precious stones |

3.33 |

6.59 |

|

Transport equipment |

3.07 |

65.31 |

| Organic

chemicals |

3.05 |

32.83 |

|

Source:

DGCI&S |

Table

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

Two items of exports deserve special mention. First,

the export of petroleum products has increased rapidly

from 2005 when domestic private refining companies

were first allowed to export, and last year amounted

to more than 15 per cent of the total value of exports.

Such exports (mainly of high-speed diesel, motor spirit

and other light oils and preparations) are dominated

by one private refiner, and interestingly the UAE

and Singapore have emerged as the major markets for

this. Second, textiles and textile products, which

were earlier among the more dynamic exports, actually

declined in value over the past year, reflecting the

increased competitive pressure from other developing

countries, especially China, in the phase after the

removal of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement.

Table 1 makes it clear that petroleum products were

not the only rapidly increasing imports. While aggregate

imports grew in value by 30 per cent over the year,

oil imports increased by 35 per cent. But the import

of transport equipment (including motor vehicles)

increased by 65 per cent, of iron and steel by 41

per cent and of organic chemicals by 33 per cent.

Even machinery and electronic goods imports increased

rapidly, reflecting the domestic investment and middle

class consumption booms.

Table

2: Major Trading

Partners

in 2007-08 |

|

Share %

|

Growth %

|

|

Exports |

|

USA |

13.02 |

-2.37 |

|

UAE |

9.66 |

13.62 |

|

China |

6.78 |

15.66 |

|

Singapore |

4.31 |

0.46 |

|

UK |

4.14 |

4.21 |

|

Imports |

|

USA |

11.3 |

37.99 |

|

UAE |

8.1 |

28.98 |

|

China |

5.62 |

38.44 |

|

Singapore |

5.51 |

0.08 |

|

UK |

4.58 |

28.15 |

|

Source:

DGCI&S |

Table

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

These commodity-wise trends were mirrored in the direction

of trade. The most significant tendency was the continuing

decline in the importance of the USA in India’s merchandise

trade. Exports to the US actually declined US dollar

terms, and imports from the US barely increased. As

a result, by the last quarter of 2007-08, China had

emerged as the largest trading partner for India,

with imports from that country significantly outpacing

exports to it. As is evident from the import data,

the increase in non-oil imports by India was dominated

by China. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have become important

in intra-industry trade in petroleum products, as

noted above.

While merchandise trade may show a large imbalance,

in the past the surplus on invisibles has generally

been large enough to make the current account positive

or in very small deficit. This was generally because

of two important inflows: the receipts from exports

of software services, which include many IT-enabled

services such as Business Process Outsourcing, and

remittances from Indian workers abroad which come

in as private transfers.

Table

3:

Invisible Payments

in 2007-08, $ mn |

|

Credit |

Debit

|

Net |

|

Total Services |

87,687 |

50,137 |

37,550 |

|

Software

Services |

40,300 |

3,249 |

37,051 |

|

Business

Services |

16,624 |

16,668 |

-44 |

|

Other

Services |

30,763 |

30,220 |

543 |

|

Private

Transfers |

42,589 |

1811 |

40,778 |

|

Investment

Income |

13,799 |

19,038 |

-5,239 |

|

Travel |

11,349 |

9,231 |

2,118 |

|

Source:

RBI |

Table

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

However, in 2007-08, while these inflows remained

large, there are other indications that invisible

payments cannot be counted upon to finance the trade

deficit to the same extent in future. Thus, while

software exports remained buoyant, they are unlikely

to remain unaffected by the slowdown in the major

market, the US, in the current year.

However, private transfers are more complex. That

part of remittances which is from the US may be adversely

affected, but the rise in oil prices in imparting

new dynamism to oil-exporting West Asian countries

where most Indian workers abroad currently reside.

Inward remittances amounted to nearly $43 bn in 2007-08,

increasing by 47 per cent over the previous year.

They were almost equally divided between inward remittances

for family maintenance, and local withdrawals or redemptions

from NRI deposits. In 2007-08, the inflows and outflows

under NRI deposits were almost the same. But a growing

proportion of withdrawals from NRI deposits are repatriated,

rather than used within the country. This ratio increased

from 15 per cent of total withdrawals in 2006-07 to

35 per cent in 2007-08.

Two negative elements of the invisibles balance deserve

more analysis. Investment income predictably exhibits

a deficit. Both inflows and outflows of investment

income have increased sharply in 2007-08. However,

the rise in inflows should not suggest that the much-vaunted

new international clout of Indian corporates is finding

expression in the balance of payments as well, as

reinvested earnings of Indian investment abroad accounted

for only a small part of the inflows. Instead, these

inflows were dominated by the interest earnings on

foreign exchange reserves held abroad, which amounted

to more than $10 bn, or 73 per cent of the total inflows

on this account.

Meanwhile, interest payments on external commercial

borrowing (ECB) emerged as one of the largest outflows

of investment income in 2007-08, amounting to $4.2

bn – an increase of 250 per cent over the previous

year! The relaxation of rules for ECBs has clearly

led to a significant expansion of such borrowing by

Indian companies, and some of this may become more

problematic as higher global interest rates and deceleration

of growth affect the ability to repay. Repatriation

of dividends and profits by multinational firms operating

in India remained high at $3.3 bn.

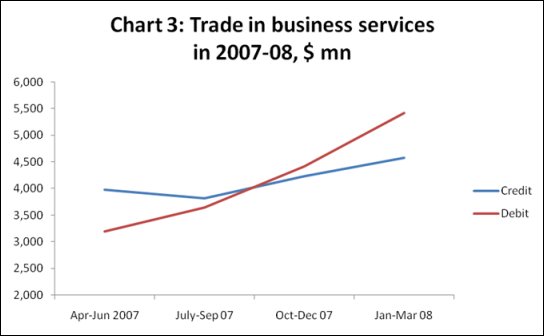

The other significant negative item is that of business

services. While the deficit on this account was small,

it is still significant because this was a positive

item until very recently. In fact, this account turned

negative only in the middle of last year, as Chart

3 shows. Within business services, over the entire

year, the categories of business and management consultancy

and architectural, engineering and other technical

services showed substantial deficits.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

The travel account of invisibles is still in surplus,

but that surplus has been declining in recent years

as economic liberalisation has increased both the

volume and value of outbound tourist and business

traffic by Indian residents. Travel payments (outflows)

increased sharply by 38 per cent in 2007-08.

Clearly, therefore, there are some areas of concern

in recent trends in the current account. When these

are combined with the clear signs of fragility in

the captial acount, including the heavy dependence

upon short-term flows, we cannot continue to treat

the accretion to the country’s foreign exchange reserves

as a sign of strength.