For the global economy, August 2011 was a particularly

bad month. A string of economic indicators released

early that month suggested that close to four years

after the onset of the global recession in December

2007 a sluggish world economy was set to sink again.

Sentiment too was at an exceptional low. Though completely

out of line and even irresponsible, the first-in-history

downgrade of US Treasury bonds by Standard and Poor's

did reflect the mood in the market. Though the assessment

was based on wrong numbers, the fact that the debt

of world's most powerful country that was home to

its reserve currency was even considered to be of

suspect quality was telling.

Besides the never-ending crisis in Europe, one factor

explaining this despondency was the fear of a second

recession within half a decade. The news from almost

all sources was disconcerting. Recovery from the recession

was still sluggish in the U.S., Japan, that had been

experiencing long-term stagnation, had been devastated

by a wholly unexpected exogenous shock. And, France

had announced that it had experienced virtually no

growth in that quarter. But the real dampener was

the release of evidence that the strongest economy

in the rich nation's club-Germany-was losing all momentum,

registering a growth rate of just 0.1 per cent in

the second quarter. The real economy crisis had penetrated

Europe's core, pointing to the possibility of a return

to recession in the Eurozone as a whole (which registered

0.2 per cent growth).

For an India that is now more integrated with the

world economy this has to be bad news. But if the

Government of India is to be believed, the Indian

economy is not likely to be very adversely affected

by the current round of global volatility. Finance

Ministry sources argue that the Indian economic growth

story is so robust that the current uncertainty will

cause no more than a minor blip in its confident trajectory.

Consider, for example, the Indian government's response

to the market collapse that followed the US debt standoff

and subsequent Standard and Poor's downgrade. While

acknowledging that India would be impacted, the effort

was to play down the likely intensity of that impact.

''Our institutions are strong and [we] are prepared

to address any concern that may arise on account of

the present situation,'' Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee

reportedly stated. He also promised that the government

''will fast track the implementation of the pending

reforms and keep a close eye on international developments.''

That response misses the point. The problem is not

that India is not adequately reformed, but that past

reforms have resulted in its greater integration through

flows of goods, services and finance with the global

economy.

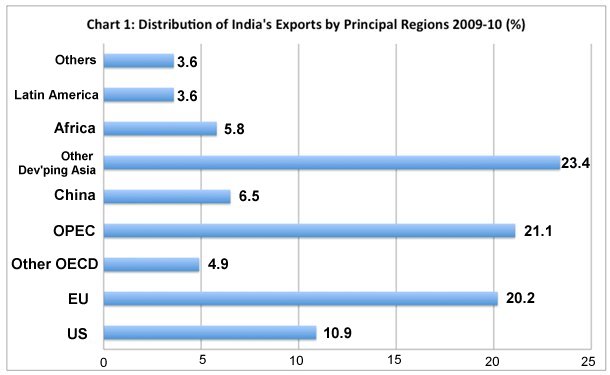

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

One

obvious and important consequence of the global downturn

is bound to be a fall in exports revenues. As Chart

1 shows, the European Union accounts for 20.2 per

cent of India's merchandise exports and the US for

another 10.9 per cent. Thus, markets accounting for

close to a third of India's exports are already stagnating

or in recession. Only two regions can, hypothetically,

counter this tendency: Developing Asia (excluding

China) and the OPEC countries. The former accounts

for a sizable 23.4 per cent of India's exports and

the latter for another 21.1 per cent. However, most

of developing Asia would be adversely affected by

the OECD downturn to a greater extent than India.

And unless geopolitical developments intervene, a

global recession would moderate oil prices and dampen

import demand from the OPEC bloc. Finally, the hope

that China would be a balancing force is of less relevance

to India since it accounts for just 6.5 per cent of

the latter's exports. Overall, India is likely to

take a hit in terms of its exports of goods, which

has been a source of buoyancy recently.

The other significant source of demand and revenue

that is likely to be adversely impacted is services.

As per Balance of Payments data, gross revenues from

the exports of software services amounted in 2010-11

to as much as 24 per cent of the gross revenues from

merchandise exports. In 2009-10, the US alone accounted

for 61 per cent of India's total software exports.

European countries (including the UK) followed with

as much as 26.5 per cent. If these two regions are

the first to be hit by the recession, it is unlikely

that software export revenues would remain unscathed.

Over the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, services accounted

for 66 per cent of the increment in India's GDP. And

revenues from software services amounted to 9.4 per

cent of the GDP from services (excluding public administration

and defence). The deceleration or decline in software

export revenues is bound to affect GDP growth adversely.

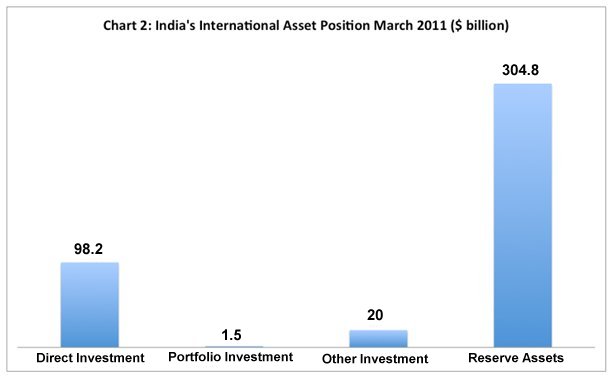

Besides export volumes and revenues, the other reason

why India is likely to be adversely affected by global

uncertainty is exposure to global finance. Direct

exposure to international financial assets, including

the now less valuable debt issued by OECD governments,

is only a small part of the problem. As the distribution

of India's gross international asset position (Chart

2) indicates, the two important forms those assets

take is direct investment and accumulated reserve

assets. Portfolio and other forms of investment are

small or negligible. Since private players largely

hold direct investment assets, the squeeze in global

demand would affect the overseas revenues of these

firms, but possibly not do too much damage to the

Indian economy.

Chart

2 >>

Click

to Enlarge

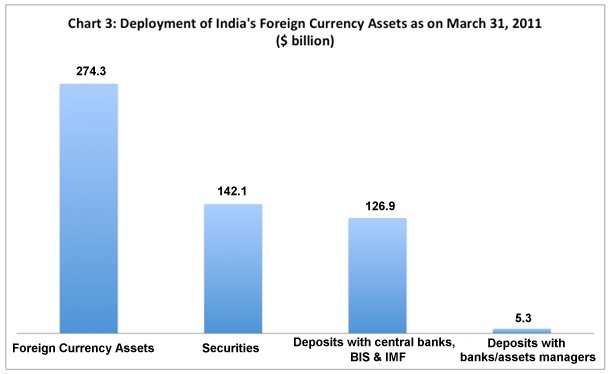

What is more of an issue is the fate of the $274 billion

of foreign currency assets (out of a total of $305

billion of reserve assets) held by India. While $127

billion of these are held as deposits with central

banks, the Bank of International Settlements (BIS)

and the IMF, as much as $142.1 billion is invested

in securities, consisting largely of government securities

(Chart 3). With the uncertainty surrounding the value

and soundness of public debt, the danger of the erosion

of the value of those assets is now significant. For

example, India holds $41 billion of US Treasury securities

that have been downgraded recently by S&P. The

balance is likely to be in the even more suspect public

debt of European governments.

Chart

3 >>

Click

to Enlarge

In addition to this, banks in India reporting to the

BIS have disclosed holdings amounting to $31.3 billion

in financial assets abroad. Of these, $14.9 billion

are the external positions of banks in foreign currencies

vis-à-vis the non-bank sector abroad. These

exposures too are vulnerable given the volatility

in financial markets in the OECD countries.

While the sums involved may be small (relative to

the $1.2 trillion held by China in US Treasury bonds,

for example) they are of significance because of the

nature of India's reserves. Unlike in the case of

China, the reserves that insure India against adverse

global responses are not earned through current account

surpluses, but are drawn from what foreign investors

have delivered in the past. They represent liabilities

that are being held as assets that on average yielded

returns as low as 2.09 per cent over the year ended

June 201 (down from 4.16 during 2008-09). If the value

of those assets is eroded, other things constant,

India's ability to cover its liabilities is eroded

as well.

Besides this there is the fact that because of the

presence of legacy capital in the country (consisting,

as of March 2011, of $204 billion of direct investment,

$174 billion of portfolio investment and $265 billion

of debt and other investments) India is vulnerable

to global investor sentiment. International finance

may assess its so-called fundamentals very differently

from the way they are assessed by the government.

Consider the issue that now captures financial market

attention: public debt. The experience in Greece,

Spain, Portugal and elsewhere suggests that finance

capital is increasingly ''intolerant'' of what is perceived

as excessive public debt. Though India's gross public

debt to GDP ratio declined from 75.8 per cent to 66.2

per cent between 2007 and 2011, it still is among

the highest in the region. India's 66.2 per cent level

compares with Malaysia's 55.1, Pakistan's 54.1, Philippines'

47, Thailand's 43.7, Indonesia's 25.4 and China's

16.5 (Eswar Prasad calculations quoted in ''Comparing

the burden of public debt'', interactive graphic on

the Financial Times website).

It is no doubt true that a number of factors make

Indian public debt less of a problem than in many

other contexts. To start with, much of public debt

in India is denominated in Indian rupees and is owed

to resident agents and therefore is unlikely to be

adversely affected by uncertainty in international

debt and currency markets. Secondly, within the country

public debt is largely held by the banking system

dominated by public sector banks. They are subject

to government influence and are unlikely to respond

to developments in ways that make bond prices and

yields extremely volatile. Given these circumstances,

public debt is not a potential trigger for a crisis

and in any case should not worry private financial

interests.

But if a wrong downgrade can make a difference to

US markets and interest rates, so can it for India's.

It is in that background that we should view reports

of S&P's statement that fiscal capacities in Asian

emerging markets, including India, have shrunk relative

to 2008. This, it has argued, would mean that in the

event of a second global slowdown: ''The implications

for sovereign creditworthiness in Asia-Pacific would

likely be more negative than previously experienced,

and a larger number of negative ratings actions would

follow.''

If, for its own reasons, S&P needs a target to

declare that some governments in the Asia-Pacific

are excessively indebted, then India is in the firing

line. India has been a favoured target of foreign

finance. And if it does not satisfy the latter's requirements,

it can fall out of favour. Clearly, a fiscal surplus

and a low public debt to GDP ratio are part of those

requirements even if for the wrong reasons. India

has neither.

*

This article was originally published in Business

Line on August 23, 2011.