As

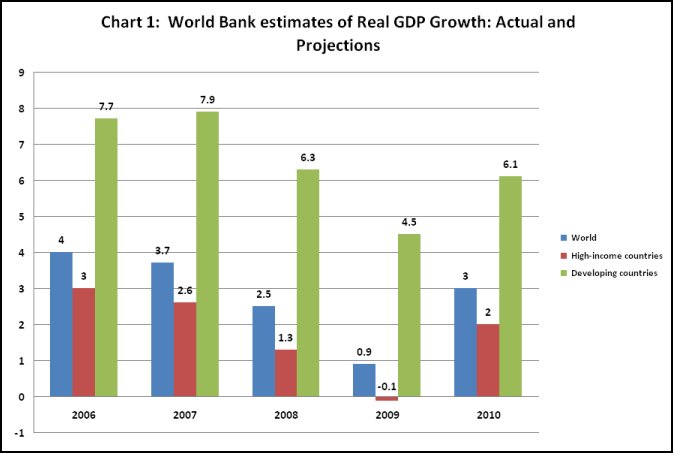

2008 entered its final month, predictions of where

the world economy is heading turned dire. The World

Bank projected world output to grow by a mere 0.9

per cent in 2009 (as compared with 2.5 per cent in

2008 and a high of 4 per cent in 2006) and world trade

to contract by a significant 2.1 per cent (compared

to positive rates of growth of 6.2 per cent in 2008

and a high of 9.8 per cent in 2006). (Chart 1). Moreover,

the World Bank could identify no possible driver for

a recovery in the coming months.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

Other projections are even more pessimistic. Chapter

1 of the UN's World Economic Situation and Prospects

2009, released in advance at the Doha Financing for

Development conference, estimates that the rate of

growth of world output which fell from 4.0 per cent

in 2006 to 3.8 per cent in 2007 and 2.5 per cent in

2008 is projected to fall to -0.5 per cent in 2009

as per its baseline scenario and as much as -1.5 per

cent in its pessimistic scenario.

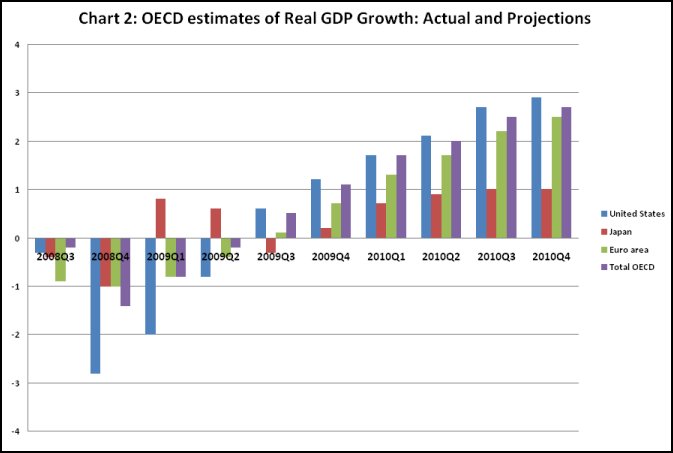

Finally, the recently released preliminary edition

of the OECD's Economic Outlook for end-2008 shows

that GDP in most OECD countries declined in the third

quarter and is likely to fall also in the fourth (Chart

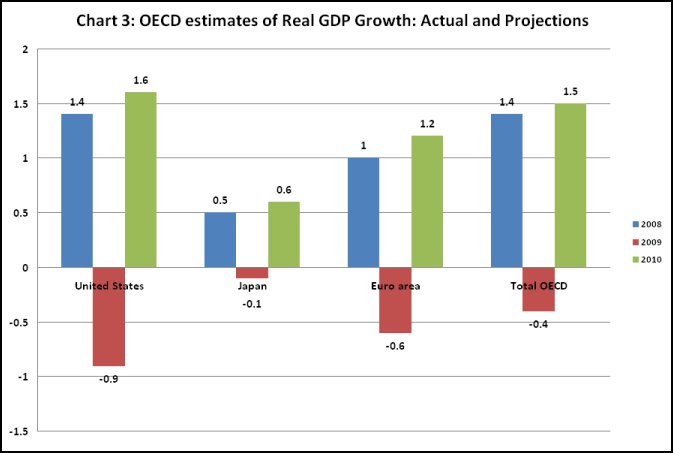

2). In the event, GDP growth in the OECD area which

fell from 3.1 per cent in 2006 to 2.6 per cent in

2007 and 1.4 per cent in 2008 is projected to fall

to -0.4 per cent in 2009 (Chart 3), and the unemployment

rate which rose from 5.6 per cent to 5.9 per cent

between 2007 and 2008 is expected to climb to 6.9

per cent in 2009 and 7.2 per cent in 2010.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

If these predictions turn out to be true, the prognosis

is that what was a recession in 2008 could turn into

a depression in 2009. Looking back, 2008 was a year

when the recession unfolded. The recession in the

US, reports indicate, is not recent but about a year

old and ongoing. Short term indicators are disconcerting,

but do not convey the real picture. Preliminary estimates

of GDP growth in the United States during the third

quarter of 2008 point to decline of half a percentage

point. But GDP growth during the previous two quarters

was positive at 2.8 and 0.9 per cent respectively.

The only other quarter since early 2002 when growth

was negative was the fourth quarter of 2007. Thus,

going by the popular definition of a recession-two

consecutive quarters of decline in real gross domestic

product-the US is still to slip into recessionary

contraction.

But the independent agency which is the more widely

accepted arbiter of the cyclical position of the US

economy is the Business Cycle Dating Committee of

the National Bureau of Economic Research. This committee,

which adopts a more comprehensive set of measures

to decide whether or not the economy has entered a

recessionary phase, has recently announced that the

recession in the US economy had begun as early as

December 2007. That already makes the recession 11

months long, which has been the average length of

recessions during the post-war period. There is much

pessimism on how long this recession would last as

well. According to the OECD, for most countries "a

recovery to at least the trend growth rate is not

expected before the second half of 2010 implying that

the downturn is likely to be the most severe since

the early 1980s, leading to a sharp rise in unemployment.''

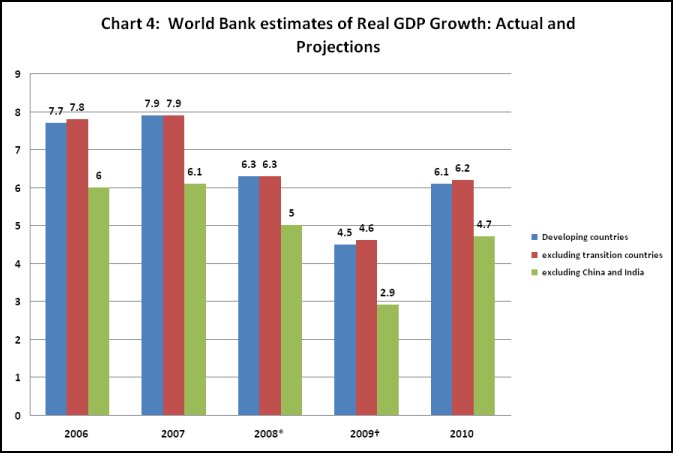

In fact, differential in the distribution of the impact

of the recession and a recovery in 2010 are the only

positive elements in analyst predictions. Most predictions,

as for example that of the World Bank, hold that the

decline in growth rates in emerging markets would

be much less than in the US. Thus, growth in developing

countries as a whole is expected to fall from 6.3

percent in 2008 to 4.5 per in 2009, only to recover

to 6.1 per cent in 2010. This is mainly due to China

and India without which the figures are more disappointing,

but still relatively creditable 5, 2.9 and 4.7 per

cent respectively. (Chart 4). In fact, expectations

now are generally that developing countries would

grow at relatively high rates in normal times. Thus,

Hans Timmer, who directs the bank's international

economic analyses and projections is reported to have

declared: ''You don't need negative growth in developing

countries to have a situation that feels like a recession.''

Chart

4>> Click

to Enlarge

However,

even here, the numbers are proving to be disconcerting.

China's growth has been slipping even if still relatively

high. But nobody can ignore the fact that manufacturing,

which is the engine of growth in that country is hugely

dependent on exports to developed country markets,

especially the US. Second, according to Bank of Korea

estimates, South Korea's economy will contract in

the last quarter of 2008 and grow at its slowest pace

in 11 years in 2009. According to its estimates, the

economy, the fourth largest in Asia, would shrink

by 1.6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008, and

grow only at 2 per cent in 2009, and 3.7 per cent

for full 2008. And the month-on-month annual rate

of growth of India's Index of Industrial Production

fell by 0.4 per cent in October, for the first time

in 15 years.

These developments make predictions of a significant

growth recovery in 2010 appear optimistic. A question

that troubles analysts is how long this recession

will last. The recovery assessments are based on the

assumptions that the crisis in financial markets would

be resolved soon and that there would be no negative

feedback loops both between the real sector and the

financial sector (which would exacerbate the financial

crisis) and within the real sector (which would intensify

the crisis in the real economy), before the positive

effects of intervention by governments materialize

in full. Such assumptions are indeed tenuous, increasing

the lack of certainty about a recovery. Thus, job

losses in the US are increasing the number of housing

foreclosures. Around 7 per cent of mortgage loans

were reported to be in arrears in the third quarter,

and another 3 per cent are at some stage of the foreclosure

process. According to the Mortgage Bankers' Association,

about 2.2 million homes will have entered foreclosure

proceedings by the end of this year. This would intensify

the financial crisis as well as dampen consumer spending,

and could worsen the downward spiral.

Yet, unemployment figures suggest that at the moment

the recession is only intensifying. On December 5,

2008, the Bureau of Labour Statistics in the US reported

that employers had reduced the number of jobs in their

facilities by 533,000, taking the unemployment rate

in the US to 6.7 per cent. This reduction-which is

the highest monthly fall in 34 years-comes after job

losses of 320,000 in October and 403,000 in September.

Total job losses through 2008 are 1.9 million. This

means that the 2.5 million jobs that President-elect

Obama is promising to deliver through his fiscal stimulus

package would just about recover the jobs lost during

the recessionary period preceding his swearing in,

and leave untouched the backlog of unemployed and

those entering the labour force during this period.

While 2008 was the year of crisis, the origins of

this crisis go back to the middle of 2007 when evidence

that homeowners who had borrowed to finance the property

they purchased had begun defaulting on their debt.

Soon it became clear that too many people with limited

or poor creditworthiness had been induced to borrow

large sums by banks eager to exploit the large amounts

of liquidity and the low level of interest rates in

the system. An unsustainable proportion of defaults

seemed inevitable. What was disconcerting in the events

that followed was that this ''sub-prime'' problem soon

spread and created a systemic crisis that soon bankrupted

a host of mortgage finance companies, banks, investment

banks and insurance companies, including big players

like Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers and AIG.

The reasons this occurred are now well known. The

increase in sub-prime credit occurred because of the

complex nature of current-day finance that allows

an array of agents to earn lucrative returns even

while transferring the risk. Mortgage brokers seek

out and find willing borrowers for a fee, taking on

excess risk in search of volumes. Mortgage lenders

finance these mortgages not with the intention of

garnering the interest and amortization flows associated

with such lending, but because they can sell these

mortgages to Wall Street banks. The Wall Street banks

buy these mortgages because they can bundle assets

with varying returns to create securities with differing

probability of default that are then sold to a range

of investors such as banks, mutual funds, pension

funds and insurance companies. Needless to say, institutions

at every level are not fully rid of risks but those

risks are shared and rest in large measure with the

final investors in the chain. And unfortunately all

players were exposed to each other and to these toxic

assets. When sub-prime defaults began this whole structure

collapsed leading to a financial crisis of giant proportions.

The crisis had a number of consequences in the developed

countries. It made households whose homes were now

worth much less more cautious in their spending and

borrowing behavior, resulting in a collapse of consumption

spending. It made banks and financial institutions

hit by default more cautious in their lending, resulting

in a credit crunch that bankrupted businesses. It

resulted in a collapse in the value of the assets

held by banks and financial institutions, pushing

them into insolvency. All this resulted in a huge

pull out of capital from the emerging markets: Net

private flows of capital to developing countries are

projected to decline to $530 billion in 2009, from

$1 trillion in 2007. The effects this had on credit

and demand combined with a sharp fall in exports,

to transmit the recession to developing countries.

All of these effects soon translated into a collapse

of demand and a crisis in the real economy with falling

output and rising unemployment. This is only worsening

the financial crisis even further.

A crisis of this nature requires holes to be plugged

at many places simultaneously. While there is wide

agreement that what is needed is a globally coordinated

and huge fiscal stimulus, the actual effort on the

ground remains fragmented and meagre. Because of this

results are disappointing, threatening to make this

crisis the most protracted in a long time. Year 2008

is likely to be remembered as a year in which a crisis

of immense proportions unfolded.