| |

|

|

|

|

Women

Workers in Urban India |

| |

| Feb

6th 2007, C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh |

|

In

the era of globalisation, it has become commonplace

to argue that trade openness in particular generates

processes that encourage the increased employment of

women, particularly in export-oriented activities. In

addition, development in general and higher per capita

incomes are supposed to lead to more employment in services

and shifts from unpaid household work to paid work,

which also involve more paid jobs for women workers.

Data

from the recent large sample employment survey of the

NSSO would appear to provide confirmation of this perception.

Work participation rates of women workers have increased

in 2004-05, not only in comparison with 1999-2000 when

they had fallen sharply, but also in comparison to a

decade earlier. However, this process needs to be considered

in more detail to see whether it is indeed the positive

process outlined above. Since this is meant to be much

more marked in urban areas, this article is concerned

with changes in employment patterns of urban women workers

in India.

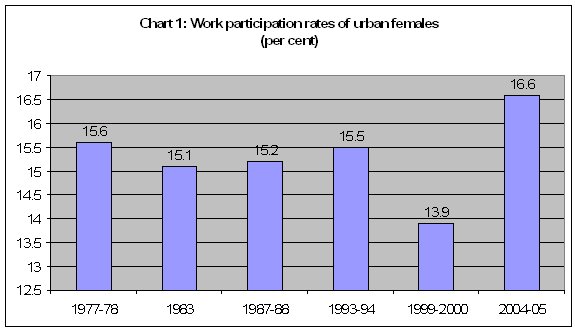

As Chart 1 shows, work participation rates have indeed

increased and in 2004-05 were at the highest rate of

the past 25 years. (The year 1999-2000 now appears to

be a significant outlier, and other problems with that

data suggest that the long terms trends are confirmed

by the most recent data.) Of course, these work participation

rates are still low by international standards, and

reflect substantial variation across states, with southern

states showing generally higher rates.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

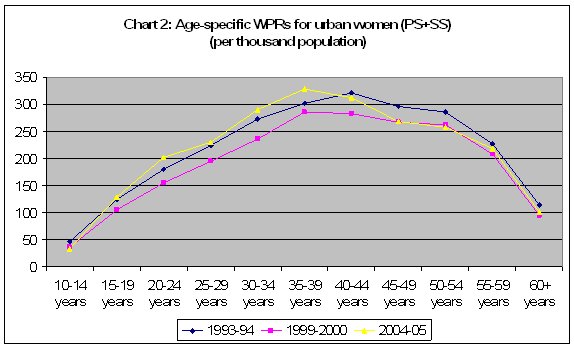

Chart 2 shows how the age specific work participation

rates for urban women have changed over the past decade.

There is a general tendency for women to enter into

paid work at younger ages than previously - participation

rates among younger urban women increased by about

2 percentage points compared to 1993-94 and 5 percentage

points compared to 1999-2000. And the peak work participation

rate for urban women has shifted from the age group

40-44 years in 1993-94 to 35-39 years in 2004-05.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

So what type of employment do urban women workers

find? Table 1 shows that there has been an overall

decline in casual employment and a general increase

in regular work and self-employment. The shift is

especially marked in the case of principal activity,

with more than 42 per cent of urban women workers

now reporting themselves as having a regular job.

When subsidiary activities are included, self-employment

assumes greater significance, with nearly 48 per cent

reporting as self-employed.

Table

1: Type of employment of usually employed urban

women |

|

Principal

Status only |

Principal

+ Subsidiary Status |

|

|

Self-employed |

Regular |

Casual |

Self-employed |

Regular |

Casual |

|

1983 |

37.3 |

31.8 |

30.9 |

45.8 |

25.8 |

28.4 |

1987-

88 |

39.3 |

34.2 |

26.5 |

47.1 |

27.5 |

25.4 |

1993-

94 |

37.2 |

35.5 |

27.3 |

45.8 |

28.4 |

25.8 |

1999-

2000 |

38.4 |

38.5 |

23.1 |

45.3 |

33.3 |

21.4 |

2004-

05 |

40.4 |

42.2 |

17.4 |

47.7 |

35.6 |

16.7 |

Table 1 >> Click

to Enlarge

This is certainly a phenomenon to be welcomed, especially

if it does indeed indicate a shift to more productive

and better remunerated activities than are to be found

with casual contracts. However, this needs to be confirmed

with evidence on the specific activities that are engaged

in and the trends in wages.

Table 2 provides the evidence on the broad sectoral

classification of work of urban women. Predictably,

agriculture shows a substantial decline over time. However,

elsewhere there are surprises. The share of manufacturing

has increased slightly, but at around 28 per cent it

is not much higher than the proportion achieved in 1987-88,

that is well before any export-led manufacturing boom

was in evidence. So the overall proportion of women

in manufacturing employment in urban India does not

support the notion of a big increase in female employment

consequent upon greater export orientation of production.

Table

2: Main sectors of employment of urban women

workers

(Principal plus subsidiary status)

|

|

Per

cent of usually employed urban women |

|

|

1983 |

1987-88 |

1993-94 |

1999-2000 |

2004-05 |

|

Agriculture |

31 |

29.4 |

24.7 |

17.7 |

18.1 |

|

Manufacturing |

26.7 |

27 |

24.1 |

24 |

28.2 |

|

Construction |

3.1 |

3.7 |

4.1 |

4.8 |

3.8 |

Trade, hotels &

restaurants |

9.5 |

9.8 |

10 |

16.9 |

12.2 |

Transport &

communications |

1.5 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

1.4 |

|

Other services |

26.6 |

27.8 |

35 |

34.2 |

35.9 |

Table 2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Even trade, hotels and restaurants, which are activities

traditionally considered to attract a lot of women workers,

do not show much increase, and the share of these has

even declined compared to 1999-2000. The clear increase,

even if not very dramatic, is for other services, which

is a catch-all for a wide range of both public and private

services, as well as both high value added high-remuneration

jobs and very low productivity low paying survival activities.

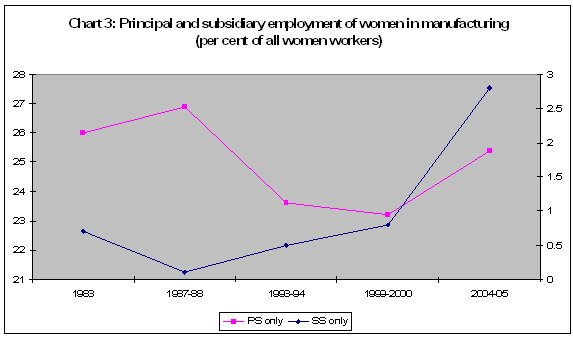

It is worth considering the patterns in manufacturing

employment in more detail, particularly because the

work of women can be easily misclassified in the available

data. In particular, the usual status definition which

includes both principal and subsidiary status activities

can be a source of confusion. It is possible that women

are classified as ''usually working'' when in fact it

may reflect underemployment or engagement in a subsidiary

activity only. Indeed, there can be substantial variation

in the type of employment contract depending upon whether

the activity is a ''principal'' one or a ''subsidiary''

one.

Chart 3 makes this very evident in the case of manufacturing

employment. In terms of principal status, the share

of women workers in manufacturing has fluctuated sharply

between 23 and 27 per cent, and there is no evidence

of a clear trend. However, the share of women working

in manufacturing in a subsidiary capacity (that is,

not as the perceived principal activity of the women

concerned) has been increasing continuously since 1987-88,

and now accounts for as much as nearly 3 per cent of

all urban women workers. This in turn is now as much

as 11 per cent of all women employed in manufacturing

- surely not a small proportion.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

What could explain this very substantial difference

once subsidiary activities are included? One important

factor may be the increase in putting out home-based

or other work as part of a subcontracting system for

export and domestic manufacturing. Such work does not

get incorporated in the employment statistics which

are based on employers' records, and this may explain

the paradox that even while women's share of employment

in manufacturing has not increased much, the dependence

of the sector - and especially of export-oriented manufacturing

- on the productive contribution of women may well have

increased.

This suggests that the direct and formally recognised

involvement of women may have stagnated even in the

period of the relative higher growth of exports over

the last decade. However, home-based subcontracting

activities, or work in very small units that do not

even constitute manufactories, often on piece rate basis

and usually very poorly paid and without any known non-wage

benefits, may to some extent have substituted for the

more standard form of regular employment on a regular

wage or salary basis.

Table 3 provides some data on the actual numbers of

women employed in various activities in urban India,

based on applying the NSSO work participation rates

to the Census estimates and projections of urban population.

The results are quite startling, especially in the context

of the much-trumpeted high output growth rates which

are widely felt to have predominantly affected urban

India in positive ways.

Thus, it turns out that relatively few sectors now account

for two-thirds of all women workers, whether in principal

or subsidiary status. Some of them are indeed the dynamic

export-oriented activities. Thus, the number of women

employed in textiles has nearly doubled and those in

apparel and garments have increased by more than two

and a half times. There has also been significant increase

in employment in the leather goods sector.

In the service sectors, there has been very little increase

in female employment in public administration, reflecting

the overall constraints on such employment, although

employment in education (mainly with private employers)

has shown a large increase. However, the biggest single

increase after apparel - and the category of work that

is now the single largest employer for urban India women

- has been among those employed in private households.

In other words, women working as domestic servants now

number more than 3 million, and account for more than

12 per cent of all women workers in urban India.

Table

3: Main sectors of employment of urban women

workers |

|

1999-2000 |

2004-05 |

per

cent change |

Food products &

beverages |

400,441 |

418,593 |

4.5 |

|

Tobacco products |

891,891 |

911,055 |

2.1 |

|

Textiles |

1,037,506 |

1,920,602 |

85.1 |

|

Apparel |

436,845 |

1,600,502 |

266.4 |

Leather & leather

goods |

72,807 |

196,985 |

170.6 |

Chemicals & chemical

products |

345,835 |

467,839 |

35.3 |

|

Construction |

873,690 |

935,678 |

7.1 |

|

Retail trade |

2,493,656 |

2,117,587 |

-15.1 |

|

Hotels & restaurants |

400,441 |

615,578 |

53.7 |

|

Finance |

273,028 |

418,593 |

53.3 |

Pub admin, defence

&

social security |

709,873 |

763,316 |

7.5 |

|

Education |

2,056,811 |

2,856,280 |

38.9 |

Employed in private

households |

946,497 |

3,053,265 |

222.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

10,939,321

|

16,275,871 |

|

|

per cent of all workers |

60

|

66 |

|

All urban women

workers |

18,201,866

|

24,623,103 |

|

Table 3 >> Click

to Enlarge

It is indeed disturbing to see that the greatest labour

market dynamism has been evident in the realm of domestic

service. This is well known to be poorly paid and often

under harsh conditions - and certainly, it cannot be

seen as a positive sign of a vibrant dynamic economy

undergoing positive structural transformation.

The newer activities that are much cited - such as IT

and finance - continue to absorb only a tiny proportion

of urban women workers, which is why they have not been

included in this table. Thus, women workers in all IT

related activities - that is, computer hardware and

software as well as IT-enabled services - account for

only 0.3 per cent of the urban women workers in this

large sample, amounting to an estimated total of 74,000

workers at most.

Similarly, women workers in all financial activities

- that is formal financial intermediation through banks

and other institutions, life insurance and pension activities

and other auxiliary financial activities - added up

to only 1.4 per cent of the women workers in urban India.

So there is clearly a long way to go before the newer

sectors - or even traditional but more dynamic exporting

sectors such as textiles and garments - can make a dent

in transforming labour conditions for urban Indian women.

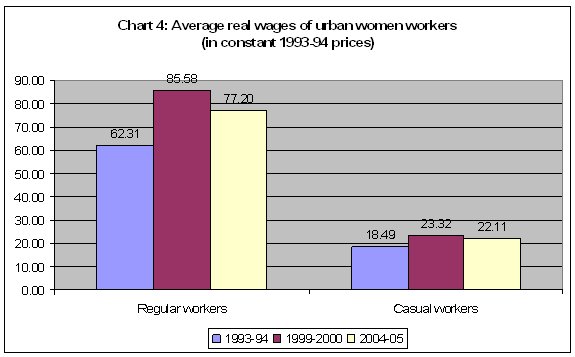

This is probably why the evidence on real wage trends

of urban women is so disappointing. Chart 4 indicates

that average real wages have fallen between 1999-2000

and 2004-05 for both regular and casual women workers,

and have hardly increased much even in relation to more

than a decade earlier. For an economy that boasts of

one of the highest GDP growth rates in the world over

this period, this is certainly an indictment.

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

|

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|