| |

|

|

|

|

Food

Prices and Distribution Margins in India |

| |

| Feb

3rd 2011, Jayati Ghosh |

|

The

dramatic increase in food inflation over the past two

years has been associated with several surprises. One

major surprise has been how the top economic policy

makers in the country have responded to it. The initial

response was one of apparent disbelief, followed very

quickly by the frequently repeated but thus far unsubstantiated

conviction that prices would come down very soon.

Then

this massive increase in the price of essential commodities

was welcomed, even by those who should know better,

as being a sign of greater material prosperity in the

country and the success of ''pro-poor'' schemes of the

government, reflected in increased demand for food.

Could it be that the economists who are running the

country apparently believed that food demand should

not increase much even in periods of significant aggregate

income growth, and among a population that has the some

of the worst nutrition indicators in the world? Is that

why they did not see any need to work towards increased

supply of food and have been so surprised by even a

slight increase in demand?

As it happens, in fact demand for food has been growing

much more slowly than could be anticipated by both income

and population growth. Much of that has to do with the

distribution of that growth, which has disproportionately

denied benefits to the poor who would naturally consume

more food. But even so, the fact that it is really the

conditions of supply – reflecting the continuing policy

neglect of agriculture as well as the nature of distribution

and the pressures on the market from speculative activity

– that have driven food prices up.

This recognition may be why the official arguments have

changed somewhat recently. Most recently the officially

stated position has been to blame inadequate existing

distribution chains – focusing on their inefficiency,

rather than any speculative pressures that could also

affect supply. This has become the most popular interpretation

of the ongoing food crisis in the corridors of power

and their stenographers in the financial press. This

has consequently led to the demand that modern corporate

retail chains (ideally with FDI) be brought in to manage

food distribution.

As a result, there are now those who have argued that

the only solution to the problem of high food prices

is to bring in FDI in retail! It is argued that this

will reduce wastage in storage and costs of transport

of food items, cut out intermediaries in distribution

and provide food more effectively to consumers at lower

prices.

Of course this argument is rather foolish, at several

levels. First of all, if the traditional supply chains

in food items are so faulty and deficient, why did they

not create such massive food price spikes earlier? Why

was food inflation relatively low in the period until

2006, despite equally rapid GDP growth and the same

system of distribution that is being faulted?

Secondly, if the problem is inadequate infrastructure,

including cold storage facilities and quicker distribution

networks from farm to market, what stopped the government

from more proactive intervention to ensure better cold

storage and other facilities through various incentives

and promotion of more farmers' co-operatives? To announce

such measures only now, as a weak response to a period

of raging food inflation is futile, because obviously

such measures operate only with a significant time lag.

This is all the more so because such proposals are explicitly

mentioned in the Farmers' Commission Report, which has

been lying with the government for half a decade now.

The idea that cold storage and other facilities can

only be developed by large corporates once they get

directly involved in retail food distribution is ridiculous

at best.

Thirdly, this entire argument completely ignores the

critical role that can be played by a public distribution

system in moderating such food price spikes and dampening

inflationary expectations and tendencies of hoarding.

Instead of accepting the failure of the government to

use this system effectively so far, the tendency is

to throw up hands and declare that only the large private

sector can save us, even though international evidence

indicates that corporate monopoly in food trade typically

increases distribution margins rather than reducing

them.

Unfortunately, though, we are forced to take such arguments

seriously because they are being repeated ad nauseum

by the media and pushed into government policies by

corporate lobbies. So let us consider what the recent

evidence on distribution margins indicates.

In fact, there is significant reason to believe that

the margins between wholesale and retail prices of many

important food items have increased in the recent period.

(See MacroScan, Businessline, 23 February 2010) The

point is that this has been happening in a period of

increased corporate involvement in food distribution

and food retail. The share of corporate retail in food

distribution in the country as a whole is estimated

to have tripled in the past four years, and has grown

even faster in major metros and other large cities.

And this is also the period when retail food prices

have shown the greatest increase!

The other point that emerges from a comparison of retails

margins across major towns and cities is that such margins

are lowest in the states (like Tamil Nadu and Kerala)

where there is an extensive, well-developed and reasonably

efficient system of public distribution that provides

a range of food items on a near universal basis to the

population. In regions where such a public distribution

system is weak or non-existent (such as Utter Pradesh

and Bihar) the margins tend to be much higher and growing

faster, even though corporate food retailing in such

regions has been expanding.

So to look at corporate retail as the solution to the

current food price increase is more than irresponsible.

There is no question that the current system of food

procurement from farmers is inadequate, faulty and often

quite anti-farmer. There is much that needs to be reformed

in the way that market yards are organised and in the

options available to farmers to get their produce to

market. There is a range of necessary and possible interventions

for this, most of which have been stated many times

to the government by various Commissions of its own.

Yet thus far the UPA government has done little about

any of these, even in terms of working with state governments

to improve the situation, and instead seems to think

that simply allowing more corporate (and FDI) activity

in retail will allow it to wash its own hands of the

matter.

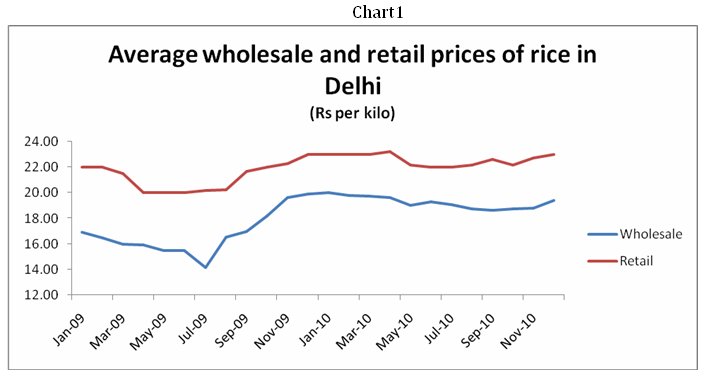

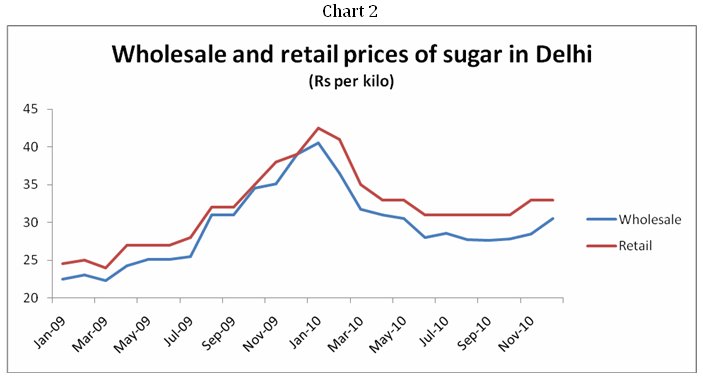

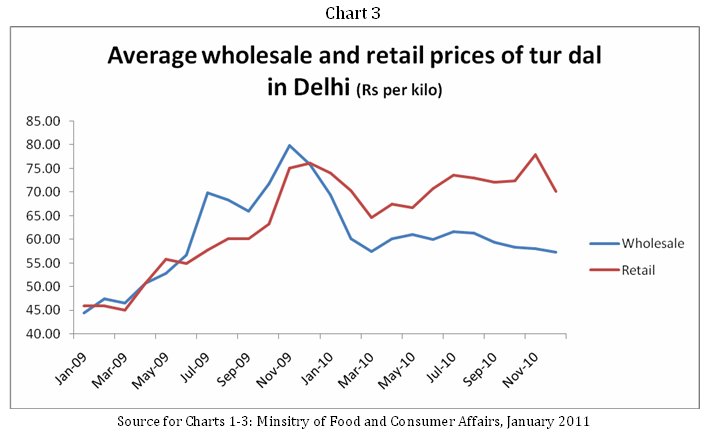

In this context, consider how retail margins have been

behaving in the very recent past, in just one location,

the city of Delhi. Charts 1, 2 and 3 describe the price

behaviour of three significant but relatively less perishable

food items: rice, sugar and tur dal.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

It

is evident that the retail prices have generally been

tracking the wholesale prices in terms of direction

of movement, but still there are some noteworthy variations.

On average, retail margins have increased for all these

commodities, and quite sharply for tur dal. This may

be the result of a number of features, and obviously

requires more investigation. But even so it is worth

noting that Delhi is a city that has witnssed a signfiicant

increase in corporate food retail. And the role of inflationary

expectations in being able to influence retail price

behaviour is obviously much greater for larger players.

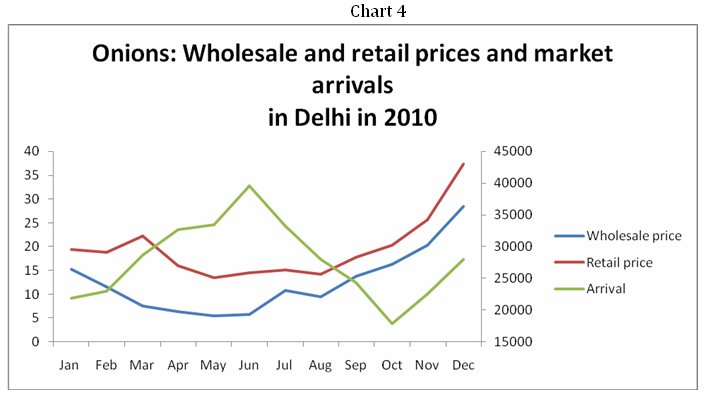

The

food prices that have been most talked about of course

are those of onions. Onion prices are widely perceived

to have great political significance, especially in

North India. Because onions like other vegetables are

highly perishable, supply conditions should play a major

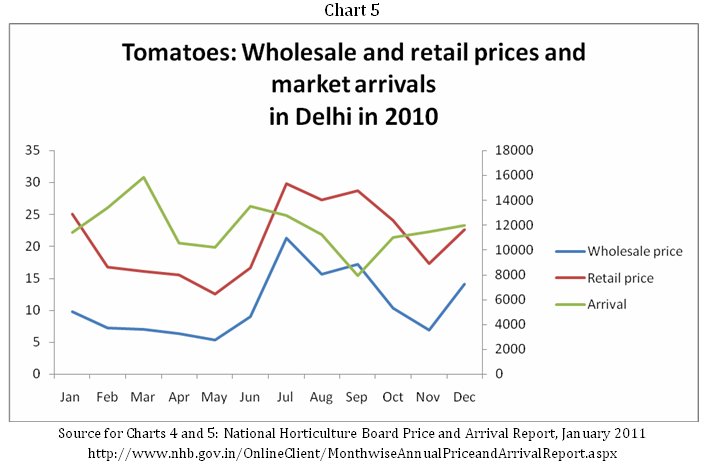

role in their price. Charts 4 and 5 describe the wholesale

and retail prices, and the total market arrivals of

onions and tomatoes in the city of Delhi.

The evidence is somewhat surprising. For much of the

period of falling market arrivals over the past year,

onion prices were rather stable and the retail margin

actually shrank. Prices started rising sharply only

in October – and this is the period after which supply

was actually increasing quite sharply! In November and

December, market arrivals increased but prices continued

to shoot up. Surely inflationary expectations and hoarding

must have played roles, along with speculative pressure,

and this was not sufficiently counteracted by public

intervention through its own food distribution network.

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

5 >> Click

to Enlarge

The case of tomato prices is similarly interesting.

It is evident that neither wholesale nor retail prices

had much relation to market arrivals, even for this

extremely perishable commodity. But what the period

of higher prices has been associated with is a significant

increase in retail margins in October and November.

Dealing

systematically with the problem of high food prices

in a context of a largely hungry population should normally

be a priority issue for any government. There are certainly

crucial medium term policies that reverse the longer

run neglect of agriculture, that must be implemented.

The issue of rapidly rising cultivation costs that are

making farming unviable once again, needs to be addressed

in a holistic way. The concerns of storage, distribution

and post-harvest technology also need to dealt with.

But in the short run, the problem cannot be avoided

by talking of astrologers and the inability of mere

humans to predict the future. Instead, creating a viable

and effective public distribution system that will counteract

tendencies to price spikes in essential commodities

is an immediate requirement.

|

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|