When

the Global Financial Crisis struck in 2008, there

were many analysts who argued that some developing

countries – especially in developing Asia and in particular

China – could not only avoid the adverse effects of

the crisis but also emerge as an alternative growth

pole for the world economy. The extent to which economic

''fundamentals'' quickly unravelled across the developing

world came as a surprise to them, as falling exports

and dramatically reversing capital flows caused economic

distress in many countries and affected even the strongest

of them.

Even in countries like China that were earlier seen

as relatively immune, only very proactive countercyclical

measures, including fiscal stimulus packages and very

substantial monetary and credit easing, allowed the

growth momentum to be restored.

Nevertheless, it is certainly true that in many parts

of the developing world, and especially Asia, the

recovery was faster and sharper than was experienced

in the North. In China and India, average incomes

did not fall but continued to grow, albeit at a slower

rate. By 2010 it was being argued that in these large

countries and elsewhere, the growth engine was increasingly

decoupled from the sputtering and hesitant recovery

that was evident in the northern countries.

Now that prospects for the world economy are once

again looking gloomy, the relatively quick recovery

in several developing countries is being seen as a

potential alternative source of expansion. As the

US gets enmeshed in politically determined fiscal

constraints and the eurozone crisis plays out to create

chronic economic weakness and potential disaster in

Europe, it is clear that expecting any positive stimulus

from these two large regions is misplaced. Instead,

eyes are turning towards the BRICs, or to the region

of developing Asia, to provide another growth pole

in what will otherwise be a sagging and even dismal

global economic story.

Chart

1 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Chart

2 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

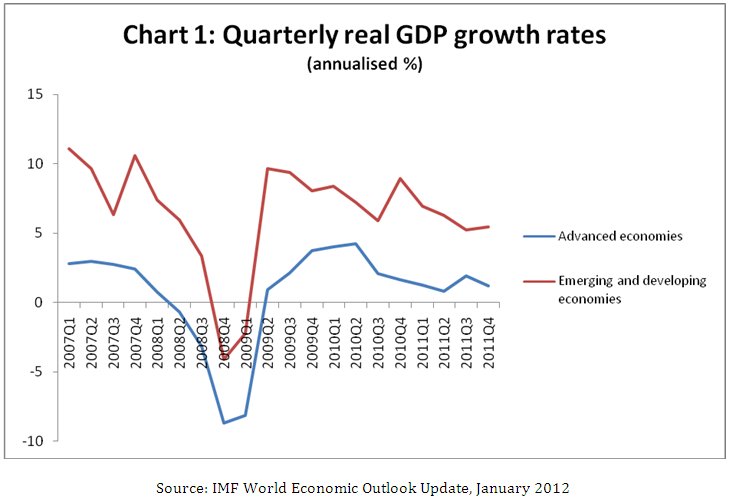

To what extent are such hopes justified? Consider

the recent trends in growth and investment, as shown

in Charts 1 and 2. As is evident from Chart 1, while

overall GDP growth rates in emerging and developing

economies remained higher than in the advanced countries,

they also turned negative in the last quarter of 2008

and the first quarter of 2009. What is more striking

is the synchronicity of even quarterly changes, between

the advanced and developing economies.

It is true that the divergence between the two groups

of economies has grown slightly in the last few quarters,

but the difference is still less than it was in 2007,

during the global boom. More significantly, the direction

of movement appears to be similar for both categories

of countries, suggesting that the forces impelling

change are still largely determined by what is going

on in Northern economies.

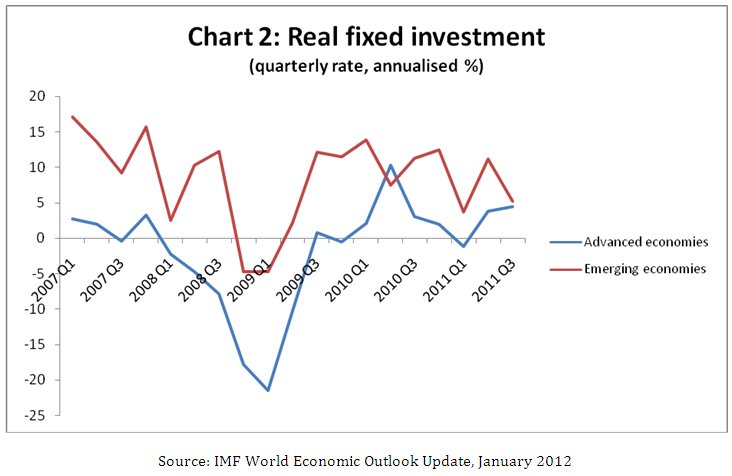

In the period just before and after the Great Recession,

a similar story seemed to be the case for fixed investment

rates. However, since the middle of 2009 the picture

of fixed investment seems to have been more mixed.

Even so, the dampening effect on investor expectations,

emanating from the gloom in developed markets, is

evident.

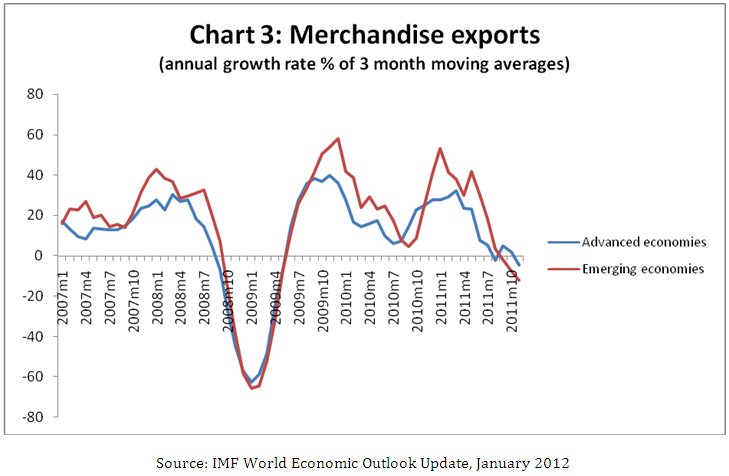

Presumably one reason for the gloom is the impact

that the slowdown in the US and Europe has on exports

of developing countries. Here the story – described

in Chart 3 - is unambiguous and depressing. Export

growth rates from both advanced and developing countries

tend to move in tandem, and if anything, merchandise

exports of developing countries (in value terms in

this chart) have been even more volatile and fallen

even more sharply, including in the very recent past.

Chart

3 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Incidentally, the picture would look even bleaker

if services exports were to be included, since service

exports have experienced substantial deceleration

in the recent past. This includes not just those services

that are affected by the slowdown in trade (such as

transport and related services) but also a range of

other more employment-intensive activities such as

tourism and IT-enabled services. Clearly, there is

little sign of decoupling in trade.

But suppose we consider specifically Asia, which is

still widely considered the most dynamic region. There

has been much talk of how greater integration within

developing Asia has already generated new patterns

of trade, investment and economic activity, and that

therefore increased Asian integration will provide

more stimulus to growth in the region even if other

areas stagnate.

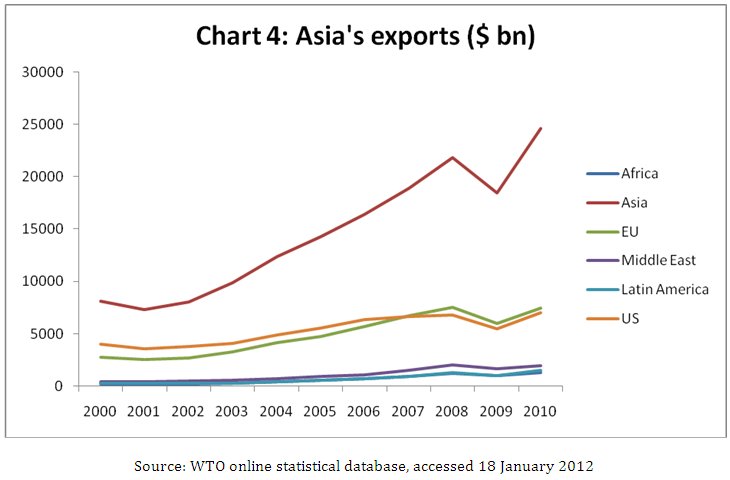

There is no doubt that intra-Asian trade has increased

significantly in the recent past. As Chart 4 indicates,

since the turn of the century, Asian exports within

the region have not only been larger but have significantly

outpaced exports to other major trading partners or

regions. Even though there was a break in the upward

trajectory in the crisis year of 2009, the subsequent

revival of intra-regional trade suggests that there

is still a lot of inherent dynamism.

Chart

4 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

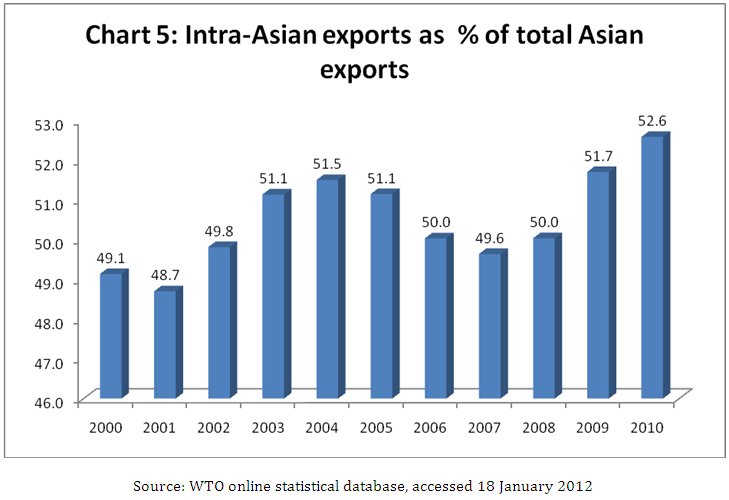

But still, it should be borne in mind that even though

intra-regional trade has increased, it is still only

around half of all of Asia's exports. Chart 5 shows

that while there have been changes in the share of

intra-regional trade, with increases in the recent

past, in this period it has been volatile around a

fairly narrow band, fluctuating between 49 and 52

per cent of total exports.

This means that global currents are still very significant

in determining trade patterns, particularly exports.

And since so many countries in the region are highly

trade-dependent and have generally chosen export-oriented

growth as the model, the slowdown in exports will

necessarily also affect levels of economic activity,

employment and future investment.

Chart

5 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

More than the quantitative indicators, it is also

the pattern of integration and the quality of the

activity that is important in this. Much of the rapid

increase in intra-regional trade in developing Asia

has been because of the emergence of a multi-location

multi-country export production platform, largely

organised around China as the final processor. This

is why more than four-fifths of such trade consists

of intermediate goods used in further production,

rather than final demand.

Such trade is obviously closely linked to the behaviour

of the ultimate export markets, which still remain

dominantly in the North, despite recent changes in

the direction of trade. Thus, for example, China (which

is the fulcrum of much of this kind of export-oriented

activity) still looks to the US and the European Union

for just under 40 per cent of its total exports. Reduced

demand from these areas will translate into reduced

demand for raw materials and intermediates required

for processing into goods for these markets. There

is already some scattered evidence that this process

has begun.

This suggests that expectations of Asia being able

to blithely withstand the latest round of economic

crisis are not just over-optimistic but probably wrong.

It also means that Asian governments have to be prepared

for this with proactive measures to cope, and that

business as usual simply will not work in the evolving

global scenario.

*This

article was originally published in the Business Line

on 20 February, 2012 and is available at

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/

columns/c-p-chandrasekhar/article2913493.ece?

homepage=true