| |

|

|

|

|

Public

Works and Wages in Rural India |

| |

| Jan

11th 2011, C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh |

|

The

''small round'' surveys of the NSSO are usually not

considered to be so good at capturing trends, because

their smaller size makes them non-comparable with the

quinquennial large surveys. However, the 64th Round

was a much larger survey than normal (with a sample

of 1,25,578 households: 79,091 in rural areas and 46,487

in urban areas, covering a total of 5,72,254 persons)

and was concerned primarily with employment and migration.

It therefore allows us to examine the effects of one

the biggest public intervention in rural labour markets

in several decades: the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural

Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGS) which was implemented

from 2006-07 and by 2007-08 had formally spread to cover

all the districts of the country.

The

MNREGS has been critiqued from different angles and

at many levels: for the corruption and leakages; the

patchy and often inadequate implementation; the non-payment

of minimum wages, and so on. But more recently, another

more unexpected kind of critique has emerged, and that

too in the highest policy-making circles: that the MNREGS

is pushing up the wages of rural workers in a manner

that is raising costs of cultivation for farmers and

making it hard for them to compete in a very uncertain

world economy.

To some it may come as a surprise that this is even

seen as a criticism. After all, surely the purpose of

any such scheme would be at least partly to improve

the conditions and the bargaining power of rural labour?

And if that is then reflected in higher wages, should

that not be proof of its success?

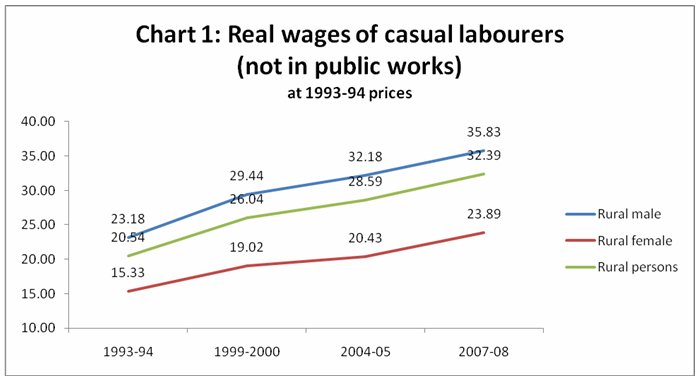

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

At

the very least, surely government representatives should

be happy when the wages come closer to the legal minimum

wage - that is, of course, if they are at all serious

about implementing their own laws. Such a tendency for

increasing wages should definitely be celebrated in

a country in which poverty and undernutrition are so

rampant especially among the rural labouring class.

In addition, they should be happy because higher wages

in the countryside also mean increased effective demand

for rural goods and services, and contribute to reviving

a very distressed rural economy through the multiplier

effects of workers' spending out of wages.

But

what is the actual evidence of such a tendency of rising

wages in rural areas? The 64th Round of NSS allows us

to compute the changes in wages of male and female casual

workers. Chart 1 shows the pattern of rural wages (deflated

by the CPIAL).

It is clear that for both male and female workers in

rural areas, the MNREGS has made a difference in terms

of increasing the wage rates for casual work. Real wages

increased for both male and female workers, and indeed

more rapidly for female workers. This was in marked

contrast to the pattern in urban areas, where wages

for casual work were more or less stagnant for female

workers.

Incidentally, it is also worth noting that casual wages

in agriculture did not increase in real terms according

to this survey; rather they remained stagnant. It should

be noted that the tendency of higher rural wages to

push up costs of cultivation can be greatly overplayed,

because wage payment typically account for less than

half and usually around one-third of total agricultural

costs. In any case, a public procurement system that

takes into account all paid labour costs (as the CACP

measures do) would adequately compensate for such costs,

which would at most lead to only a marginal increase

in prices.

But to what extent can the increase in rural women's

wages be ascribed to the effects of the MNREGS? Quite

a bit, it turns out. It is well known that women's involvement

in this scheme has been much greater than was mandated

by the 30 per cent reservation of employment and also

much greater than expected in many parts of the country.

Chart 2 shows that, while involvement in public works

accounted for a much greater proportion of economic

activity in rural India, the increase was particularly

sharp for rural women. Between 2004-05 and 2007-08,

the days of employment of rural women in public works

increased around 4.4 times, a remarkable shift in terms

of involvement in paid work.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

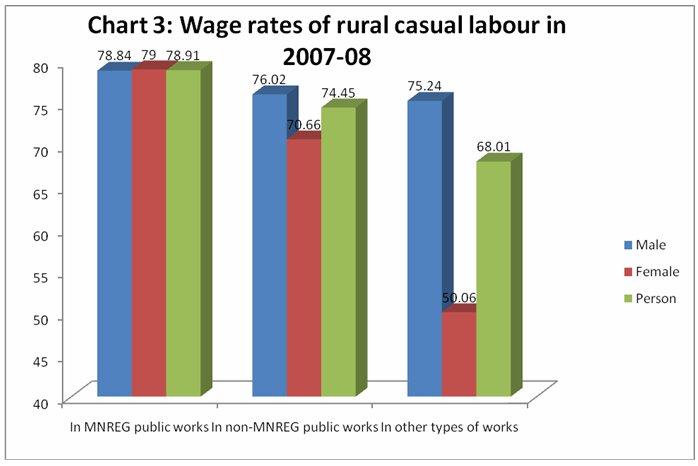

An important reason for that emerges from Chart 3:

the MNREGS has been so successful in attracting women

workers because there is hardly any gender gap in

the wages paid, unlike almost all other forms of work

in rural areas. In fact, the average wage received

by women workers in MNREGS was slightly higher than

the average wage received by men. This compares very

favourably even with other form of public works, but

particularly with non-public work, where the gender

gap remains huge. Further, on average wages received

in MNREGS were significantly higher than those received

by casual labour in other kinds of work.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

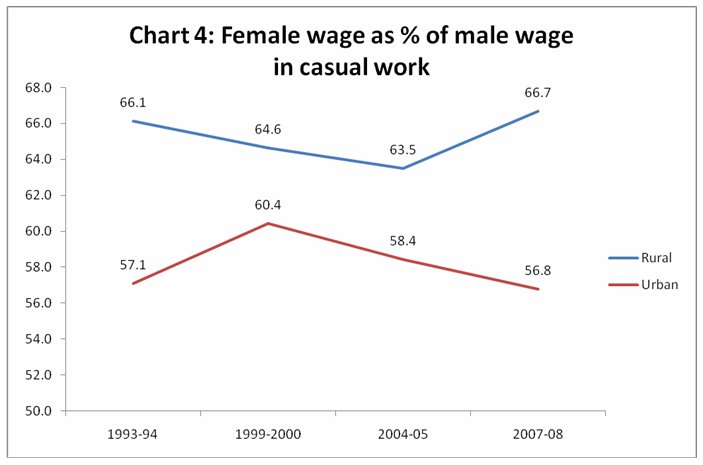

A look at the trends in gender gaps in wages confirms

this point. Chart 4 shows female wages as a percentage

of male wages in both urban and rural parts of the

country. India already had one of the highest gender

gaps in wages in the developing world, and in urban

India this gap worsened in the first half of the past

decade and remained at around the same level thereafter.

However, in rural India there has been a significant

reduction in the gender gaps in the latest period,

and this can be related very substantially to the

impact of the MNREGS. This impact is both direct,

in terms of the higher wages paid to women in this

scheme; and indirect, in terms of the effects on women

workers' reservation wages and bargaining power.

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

Surely, even the most diehard opponent of the scheme

would find it hard to argue that this is a bad thing.

Indeed, even if the MNREGS has been only marginally

successful in raising male wage rates in the countryside,

the effect of the scheme in raising female wages is

already a major positive feature that should be applauded.

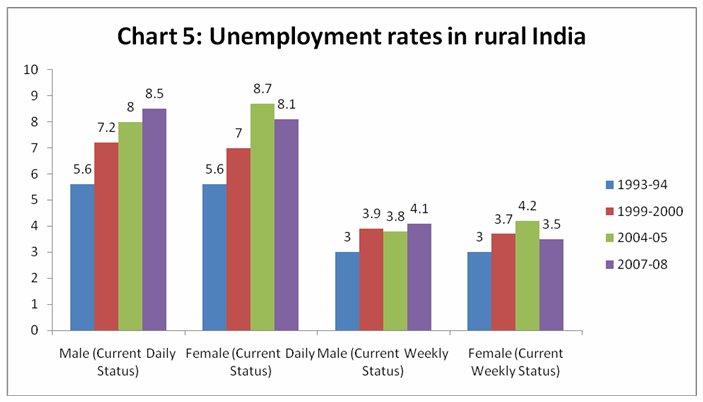

Chart

5 >> Click

to Enlarge

The gender-differentiated impact of the scheme in terms

of the impact on rural labour markets continues to be

evident in terms of unemployment rates, shown in Chart

5. For male workers, there has been no impact on this

feature: in fact, unemployment rates (by both Current

Daily Status and Current Weekly Status indicators) have

continued to rise. However, female open unemployment

rates have shown decline, albeit relatively marginal

falls from their previous highs.

What

this does indicate is that, for all its flaws, limitations

and difficulties, this scheme has already had positive

effects on women workers in rural labour markets. It

has caused real wages to rise, gender gaps to come down

and open unemployment rates of women to decrease. Before

the scheme was implemented, these were not really anticipated

as likely outcomes. But this positive impact may well

have longer term benefical effects on social and economic

dynamics in rural India. |

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|